Attaleia was an important city in the Anatolian Byzantine world. It is still a famous city for tourism due to its beautiful coastal geography, with Antalya being one of the most popular spots to visit in Turkey. But its history goes back much farther than its Turkish period, it was at times among the most important cities in the Byzantine world.

The city was allegedly founded by a man named Attalus II from the ancient Greek Kingdom of Pergamon. It was heavily fortified with a good natural harbor, and far from a river to prevent silting of the harbor.

EARLY ROMAN ATTALEIA:

Of course the Byzantine Empire is the Roman Empire, but we will use this distinction to divide its early and medieval history. The region Attaleia is in, then known as Pamphilia. It was a highly urbanized region with several cities close to each other. By the early Roman period Pamphilia had five major cities – Attaleia, Perge, Syllaion, Aspendos, and Side. Hadrian visited the city and a special gate was built to honor the Emperor’s presence around 130AD. However, despite initially being relatively unimportant – in the long-term Attaleia would be the most important in the Byzantine era of Roman history.

It was not mentioned a lot in Late Antiquity, but it seems Constantine found some statues there to take back to Constantinople. The little evidence we have indicates the city was doing pretty well in this time, but probably wasnt the greatest city of the region.

DECLINE OF PAMPHILIA:

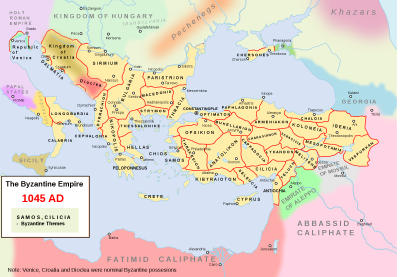

Though Byzantium never stooped as low as western Europe, there was a loss of urbanization in large areas of the Empire during the medieval period. Arab raids were highly destructive, the fact there were 5 cities so close to each other made the area a big target for raids. Perge was no longer inhabited by the 8th/9th century, Aspendos was likely just a small fort, and Side severely declined as well. Syllaion survived as a small theme headquarters and fortress, but also eventually faded away. This left just Attaleia as a major city in the once highly urbanized region.

“BYZANTINE” ATTALEIA:

Clive Foss wrote that “Attaleia was defended with such strength and effectiveness that, virtually unique among Byzantine cities, it seems to never have been captured.” This is no small achievement considering the Arab threats to Anatolia. Attaleia was able to survive inside of its walls with access to the sea. Emperors restored and strengthened the defenses of the city. Around the year 910 the ancient wall circuit was reovated, overseen by the droungarios Stephen Abastacus. In the years between 910-916 there was an outer wall added to further the defenses during the reigns of Leo VI and Constantine VII.

It also hosted an important naval base for the Roman fleet, helping to protect it from Arab raids by sea. The powerful fleet stationed there could also be used on the offensive. Ships from Attaleia were sent to attack Carthage in 689, briefly liberating it, but ultimately leading to the Arabs destroying it. In the 9th and 10th centuries ships were taken from Attaleia for the various attempts to liberate Crete from the Arabs, most of which ended in defeat. The Attaleian fleet also had to spy the Arabs in the Emirates of Tarsus and Adana. Offering naval support to Byzantine Cyprus was also a major concern, and a threat to any usurpers on the island.

In 911, the Cibyrrhaeot theme sent 15 dromon(warships) which each required 230 men to row, as well as 70 marine soldiers onboard. It also sent 16 large transport ships known as pamphyloi, with 130-160 rowers per ship, thus they were likely slower ships. Pamphyloi were named after the region of Pamphylia. In total the force sent from Attaleia to Crete in 911 totalled “6,660 men, plus an additional force of 5087 Mardaites” according to Clive Foss. Less details are known, but the theme also sent soldiers which helped in future expeditions, including the successful liberation by Nikephoros Phokas.

It was the capital of a naval theme, themes being militarized provinces with their own armies. This was called the Cibyrrhaeot theme, and it was highly strategically valuable. The purpose of this theme seems to have been to prevent Arab fleets from easily entering the Aegean and approaching Constantinople. It was also an important trade hub for trade with the Arab world and Cyprus. It is a rare city which seems to have kept close to its ancient size even in Byzantine times, a product of its prosperity and security. Attaleia even had a large Jewish community. This Jewish community would always pay the ransom of any Jews captured by Arab pirates which came to Attaleia to sell prisoners.

The Arab source Ibn Hawqal wrote that(paraphrased in the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium): “Atteleia was the center of taxes on goods brought by trade or piracy from Muslim lands; the revenue from this amounted to 300 pounds of gold. He also states that the city was directly subject to the Emperor and paid no taxes.” I am not sure if he fully understood the Byzantine political situation, but it certainly offers insight into the importance of Attaleia.

In 977, the city was involved in a rebellion against Basil II to side with Bardas Skleros. The imperial admiral was arrested and thrown into chains, and the fleet was a major component in the rebellion.

COMMERCIAL CENTER:

The city was a trade emporium, with goods from the interior of Anatolia exported through its port, often to Constantinople. Commodities such as wheat and barley were often purchased by the government to feed Constantinople and the Roman armies. The city also had fruitful orchards. It was one of the key regional trade cities such as Trebizond and Thessaloniki. Interior provinces near enough to the city also imported the goods they could not produce through Attaleia. Despite having major fleet, piracy was an issue in the area.

DECREASED IMPORTANCE/SELJUK INVASIONS:

Attaleia’s security did not last forever. It was prioritized in imperial planning as a key defensive point in the centuries of conflict with the Arabs. However, eventually the naval themes were greatly diminished and the Emperors had a more centralized naval force. Perhaps revolts like that in 977 discouraged the Emperors from allowing a provincial fleet to linger in the capital. Attaleia was thus no longer what it was in a strategic sense even though it remained important.

It is unclear whether Anatolia fell to the Sejuks during the years after Manzikert. Clive Foss explained in his book that: “History does not record the fate of Attaleia in the aftermath of the disaster at Manzikert when Asia Minor fell under Turkish control, but it is evident from its later history that the city, if it held out at all, did do as an island in enemy territory. The new age opened with the concession to the Venetians of free trade in Attaleia and other ports of the Empire, granted by Alexios Komnenos in 1082, and renewed by his successors in 1148, 1187, and 1199. The magnitude of the concession, which could have entailed a serious loss of revenue for the Empire, was the result of the urgent circumstances of the time, in which the Empire was fighting for its existence and could barely maintain its position in Asia Minor.”

KOMNENIAN ERA:

Regardless of whether it briefly fell or not, it was part of Roman imperial territory during the Komnenian era. The city was so well fortified that it seems to me taking it back would have required an effort that would be mentioned in the historical sources. Despite diminished Anatolian territory and trade concessions to domineering Venetian merchants, the city still did pretty well in the Komnenian era.

The Emperors still fought to protect the city. It was an important fortress on the southern anatolian coastal strip of land. To get to Cilicia Emperors would march by Attaleia. In 1103 an imperial army did so en route to Cilicia. In 1110 Alexios sent an army to defeat the Seljuk raiders devastating the area around Attaleia and threatening it. But it was a very isolated city until 1120, when Emperor John II Komnenos took Sozopolis and other territories which opened and secured roads to Attaleia. But even that security was intermittent.

John himself had to fight his way to Attaleia in 1142 despite nominally controlling the lands leading to the city. Other times, such as in 1137, he chose to go there by sea to avoid the dangerous roads. The mobility of Seljuk raiders meant they could dart in and out of the borderlands easily, and ambushes were a major threat. The intentions of John were to secure this area further, but tragedy struck the Emperor in Attaleia when his son and heir Alexios died there. The Emperor himself died down the coast in Cilicia the next year. His younger son and successor, Manuel Komnenos, never put the same energy and focus on the area as John did.

During the Second Crusade, it is recorded that the French soldiers under King Louis VII needed supplies and a market was set up at Attaleia. However, the local Romans did not trust them. The French camped outside the walls, and according to the Crusaders the supplies were sold at high prices. This showed the tough situtation the city was in, although the land was fertile, cultivation on a large scale was impossible because the nomads would ride in and raid it immediately. The Crusaders had to fight off Turkish raiders as they camped outside the city. Even horses and livestock taken out to graze were escorted by soldiers. The city by this time was no longer an exporter of food, it was an importer. The city still had its large double walls, likely the only reason the Crusaders did not take the city as tensions rose, according to Clive Foss.

In 1158 Emperor Manuel Komnenos did visit Attaleia as he went east to Cilicia. It seems he had the walls repaired at this time as well. Perhaps recognizing full control was unlikely to happen, he went about fortifying the cities on the southern coast of Anatolia. The fickle nature of Byzantine power in Anatolia sounds far more like a Wild West world than the solid colors of control on the maps indicate. What follows supports that conclusion…

FALL OF ATTALEIA:

When Manuel died in 1180, the fragility of Byzantine Anatolia was laid bare. Attaleia had the walls to resist a large-scale Turkish attack in 1180 as they looked to take advantage of the succession. In a western source for the Third Crusade, the city was described as under imperial control in 1191. But the Turks had fully conquered the surrounding lands. In a Byzantine document from 1199, it is listed as a province.

The tragedy of the Fourth Crusade led to its downfall. An independent Italian force under the command of a certain Aldobrandini seized Attaleia around that time. In 1207 the Turks attacked him, and he called on the Crusader forces in Cyprus for help. But they quarreled and the Seljuks took Attalaia on March 5, 1207. Despite one revolt in the early 13th century, Attaleia/Antalya has remained a Turkish city since that time.

SOURCES:

Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

Cities, Fortresses, and Villages of Byzantine Asia Minor by Clive Foss.