The Hagia Sophia is without argument the most iconic Byzantine structure ever built. I think in modern times it is had to fully appreciate just how special it is. For one, it no longer possesses all of its former treasures. Secondly, and more importantly, we have larger buildings. But it is crucial to keep in mind just how rare an experimental and boundary pushing construction like this structure really is. It was so great it was hard to even copy, and the Romans never had the resources needed to build something like this after it was built. Not until the Ottomans were there such large scale constructions in Constantinople. Probably it is the most iconic building for all of Orthodox Christianity, and even for the Ottoman Turks as well. It has been an Orthodox Church, a Catholic Church, then an Orthodox Church once more, an Ottoman mosque, a museum after the founding of modern Turkey under Ataturk, and back to a mosque in the present under Erdogan.

NAMES:

It is known as the Hagia Sophia, Hagia Sofia, Ayasofya in the Turkish form, and I am sure other versions of that name as well. I have seen it referred to as “St. Sophia” as well. In the Byzantine period, it was frequently referred to as the Great Church (Megali Ekklesia/Μεγάλη Εκκλησία) by the Romans themselves. This was because it had the highest status of all the churches in the city, anyone would have known which church was the Great Church.

THE OLDER HAGIA SOPHIAS:

The Hagia Sophia we all know today is not the original building by any means. The first church was known as the Great Church, as at the time it was the largest church in Constantinople. I could not find a reconstruction of this first church. This first Church was built on the same site as the present Hagia Sophia in 360AD by the Emperor Constantius II, son of Constantine the Great. Not much is known about this building, but it is said to have had a wooden roof and have been more rectangular or U shaped. Riots broke out in the early 5th century which destroyed this building.

Theodosius II then had a new second church built, which was finished in 415. A simple reconstruction of which you can see in the top left picture of the collage at the beginning of the first video. Some foundations and sculptural fragments still exist from this church. It was a rectangular shaped basilica nowhere near as splendid as the Hagia Sophia we all know today, but still an improvement over the previous design. It was built by an architect named Rufinus. It had elaborate carvings, similar to some parts of the decorations of Hagios Polyeuktos. There was a frieze of lambs which symbolized the 12 apostles of Christ, fragments of which still exist. It also had colorful mosaics and sculptures even on the outside of the building, unlike the modern Hagia Sophia. This church sadly met the same fate as the first, and suffered from a massive fire due to rioting in 532. These riots are the more famous Nika riots, which nearly toppled Justinian. Instead, Justinian survived to begin a massive construction project which would change the landscape of Constantinople forever, presenting us with iconic structures such as Hagia Sophia and the Hagia Eirene. Out of the fires of the two old churches emerged the treasure that is the Hagia Sophia we all know.

FROM THE ASHES OF NIKA THE SPLENDOR OF CHRISTENDOM IS BUILT:

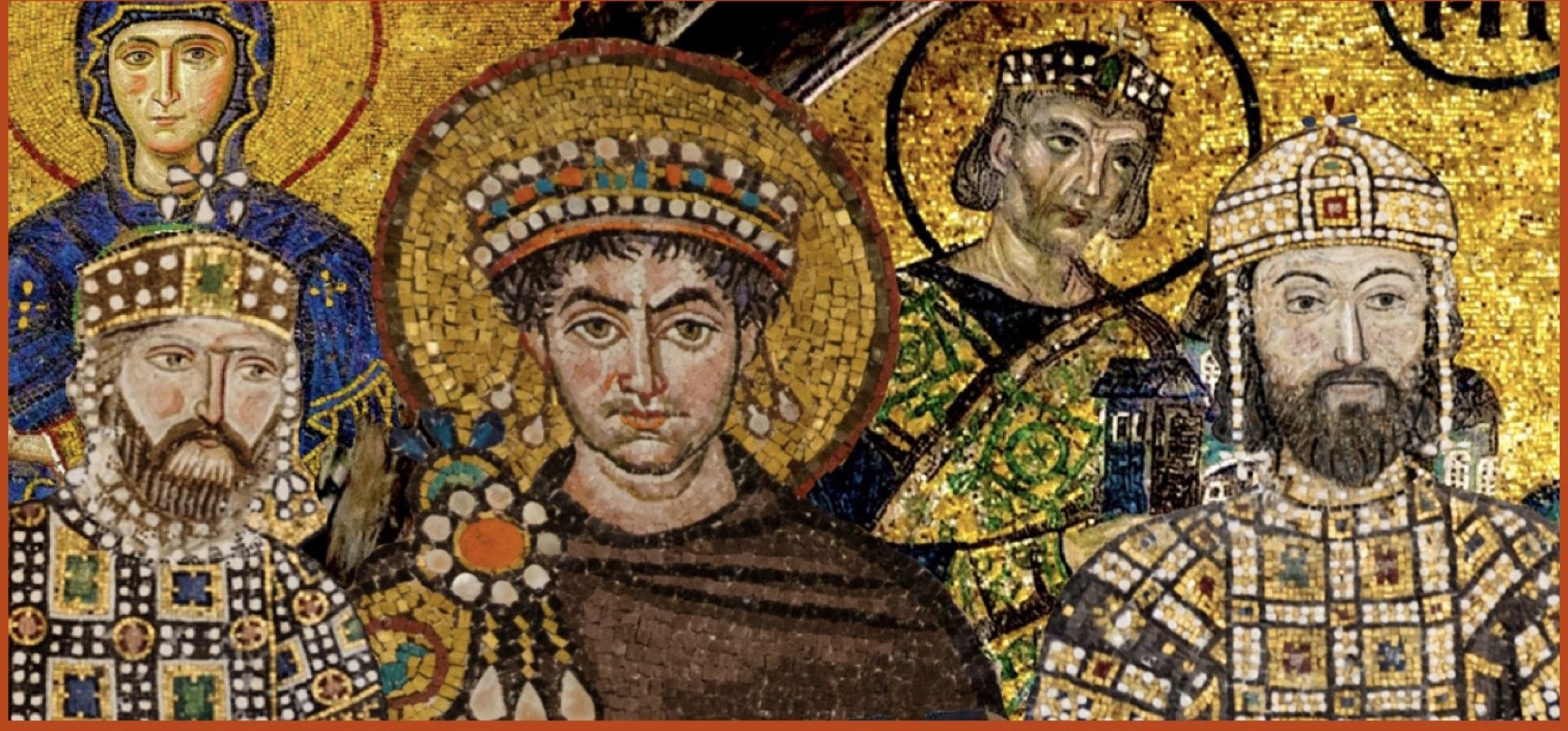

After the smoke stopped rising from the ruins of the church built by Theodosius, Justinian set into motion a church that would help the residents of Constantinople forget their old basilica. Romanos Melodos claimed that construction started the day after the Nika riots. Prokopios wrote that “the Emperor Justinian built not long afterwards a church so finely shaped, that if anyone had enquired of the Christians before the burning if it would be their wish that the church should be destroyed and one like this should take its place, showing them some sort of model of the building we now see, it seems to me that they would have prayed that they might see their church destroyed forthwith, in order that the building might be converted into its present form.”

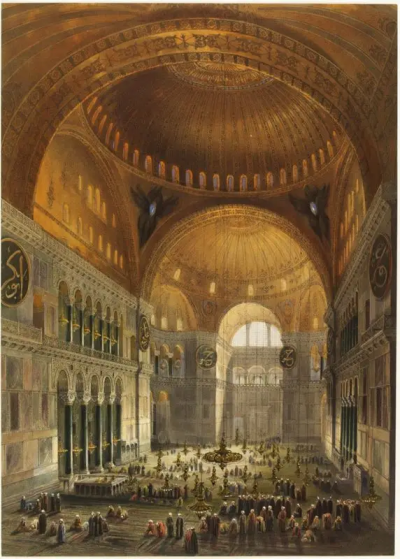

Another excerpt from Prokopios describing the great church: “So the church has become a spectacle of marvellous beauty, overwhelming not only to those who see it, but to those who know it by hearsay altogether incredible. For it soars to a height to match the sky, and as if surging up from amongst the other buildings it stands on high and looks down upon the remainder of the city, adorning it, because it is a part of it, but glorying in its own beauty, because, though a part of the city and dominating it, it at the same time towers above it to such a height that the whole city is viewed from there as from a watch-tower. Both its breadth and its length have been so carefully proportioned, that it may not improperly be said to be exceedingly long and at the same time unusually broad. And it exults in an indescribable beauty.”

Justinian tapped Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles to be his architects. Anthony Kadellis speculated about how Anthemios and Isidoros might have been chosen as architects. He pointed out that Justinian employed many architects and builders, “including the mēchanikos Theodoros, who had been sent in 531 to Jerusalem to build the New Church to the Mother of God; Victorinus, active in the Balkans and Greece; and the mēchanopoios Chryses of Alexandria, employed along the eastern frontier, especially at Dara. The answer may simply be that Anthemios and Isidoros were the most qualified men present in Constantinople: Theodoros was in Jerusalem, Victorinus was probably not qualified (and absent), and Chryses was in the East. Work on the new church began quickly, so fast that it has been surmised that the plans had been laid before the riots occurred.”

Interestingly there was a Praetorian prefect in office when the construction on the Great Church began in 532, a pagan by the name of Phokas. The unpopular John the Cappadocian had been removed from office after the Nika riots to appease the citizens, and this Phokas was chosen as his replacement. He had helped rebuild Antioch after fires and an earthquake, making him ideally suited, even Prokopios praised him. Anthony Kaldellis, an expert in primary sources, wrote that Ioannes Lydos wrote glowingly about Phokas, saying he was great at his job, and said that funding for the Hagia Sophia was part of his job. It is possible he was responsible for some of the overseeing the grand construction, and Lydos says he was able to do so without using the unjust means of John the Cappadocian. Phokas was later purged along with other pagans and took his own life. This is a less known part of the story of Hagia Sophia.

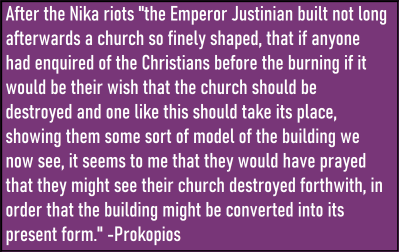

For the new building instead of a fire-prone wooden roof an architectural masterpiece, a domed roof was installed. The church used the best techniques available, synthesizing Roman architecture into a unique work. It has a dome nearly as large the Pantheon in Rome, and also used features from St. Polyeuktos. It had flexible masonry which has helped it endure earthquakes for 1500 years.

The construction began in 532 and was completed unusually fast by 537. Five years is an extraordinarily fast period for a project of this scale, especially in pre-modern times. On December 28 in 537AD the talk of the town in the city of Constantinople would have been the Hagia Sophia, which was completed the previous day on December 27. Everyone who saw it from afar would notice the largest building in the city, and arguably the most beautiful church ever, which rose from the ashes of the Nika riots. In the words of Procopius, “those who are in the church delight in what they see, and, when they leave, magnify it in their talk. Moreover it is impossible accurately to describe the gold, and silver, and gems, presented by the Emperor Justinian, but by the description of one part, I leave the rest to be inferred. That part of the church which is especially sacred, and where the priests alone are allowed to enter, which is called the Sanctuary, contains forty thousand pounds’ weight of silver.” It immediately became the defining monument of Constantinople, and one which was clearly well made in typical Roman fashion, as it has held up so so well.

This building has been impressing people for nearly 1500 years. It is actually amazing that this structure is still so intact. It is a testament to it’s great construction technique that in such an earthquake prone area it is in such great condition. According to a study of its construction material “the mortars of Hagia Sophia display considerable mechanical strength along with longevity, and may be considered as early examples of reinforced concrete…The main piers are comprised of stone masonry of almost rigid stone blocks and relatively compliant mortar, while the main arches, dome, and portions of the main piers and buttresses above it are comprised of brick masonry with thick characteristic mortar joints. The dated mortar samples examined proved to be resistant to continuous stresses and strains due to the presence of the amorphous hydraulic formations…which allows for greater energy absorption without initiations of fractures.

Elena Boeck wrote the following passage in the The Bronze Horseman of Justinian in Constantinople: the Cross-Cultural Biography of a Mediterranean Monument. It helps explain the architectural challenges this building overcame:

“Hagia Sophia was not an easy building to complete. The trouble came when its enormous piers were being spanned with arches: ‘unable to carry the mass which bore down upon them, somehow or other suddenly began to crack, and they [the piers] seemed on the point of collapsing.’ Prokopios tells us that Justinian was able to calm his terrified builders; showing divinely inspired understanding of architecture,’ ‘he “commanded them to carry the curve of this arch to its final completion.’ The emperor followed the command with a lesson in physics: ‘For when it [the arch] rests upon itself … it will no longer need the props beneath it.’ A second problem with the arches was again effectively resolved by the emperor. Justinian, naturally, was proven correct (until the point when the first dome collapsed in less than twenty years and had to be hastily restored). Though the fabric of the building does not directly reveal the workings of divine intervention, it shows several architectural solutions aimed at preventing further deformation of the piers, and ensuring stability of the entire structure. Despite these interventions, Hagia Sophia effectively masked its architectural weight with a long-standing Roman solution: its exterior covered in marble (i.e. non-structural marble work), the building had a luminous, glowing appearance. The luminosity of the exterior was matched by the golden mosaics of the interior – ‘overlaid with pure gold, which adds glory to the beauty…’ Hagia Sophia was a landmark in the nodal space of imperial power – it was the temple of Justinian’s forum (the Augoustaion).” –Elena Boeck, Professor of History of Art at DePaul University and specialist in the arts of the medieval Mediterranean world.

I cannot stress enough that the medieval exterior was far far more beautiful than the modern Hagia Sophia, having proconnesian marble panels decorating its exterior instead of the faded facade one can see today. The marble panels really made it look more bright, and Roman, than the current look. There were colored columns of various stone materials, as well as marble revetment much of which is still in Hagia Sophia. The columns were crowned with intricate capitals that today still bear Justinian’s monogram. Inside good and silver religious treasures were abundant. Porphry, the imperial stone, was also used to decorate the church. The church immediately became the Patriarchal Church after its completion. However, the quick building time turned out too good to be true. Earthquakes hit in 553 and 557, cracking the dome part of which collapsed in 558. The likely infuriated and embarrassed Justinian ordered repairs on his grand achievement to be done Isidore the younger, nephew of the original architect Isidore of Miletus. After being repaired and re-engineered with the stronger dome we see today, the church was re-opened in 562. It took about as long to rebuild and redesign the dome as it took to build the entire church. The mosaics took a while to complete and weren’t finished until during the reign of Justin II, who succeeded Justinian.

A CENTER-PIECE OF BYZANTIUM:

Even though the building Justinian had envisioned has lasted until modern, times it has changed a lot. It is easy to casually downplay the sheer magnitude of the Byzantine timeline. In 624 it lost many of its treasures as the Roman Empire was nearly destroyed by the Persians. Emperor Herakleios made the sensible but controversial decision to melt down church valuables, including some from the Hagia Sophia, to launch the counter attack which defeated the Persians. In this way the treasures of the Church helped save the Empire. After victory against Persia, Herakleios retrieved the True Cross which had been taken by the enemy and had it brought to Hagia Sophia before returning it temporarily back to Jerusalem. Herakleios did his best to pay back the church after his victory until the Arabs emerged.

The Church was more than just a really impressive looking building, it was a center of the power of the Byzantine state. It was the the church of the Patriarch of Constantinople, the most important church leader for the Romans, whom was appointed by the Emperors themselves. But it was also a place where Emperors would perform court rituals. A victorious Emperor would march from the Golden Gate down the mese to Hagia Sophia. Starting in 641 with Constans II, the Emperors were coronated in the Hagia Sophia. Most likely the stood on the omphalion, which still stands today (video below). It was also a place where criminals could seek refuge, it was a place where law could be administered by the church officials, such as trials of murderers. It was a complex building with a complex role in society.

The Hagia Sophia was a place where the power of the Church and Emperor could combine and collaborate, but also compete and clash. One of the most famous examples is the conflict between Leo VI and Nicholas Mystikos. Leo had three marriages, which the Church forbade, and wanted a fourth. This was very sinful according to the Church, and they did not want to certify the fourth. At some point Leo was banned from Hagia Sophia by the Patriarch Mystikos. In front of the very same Imperial door as the mosaic, Leo was reportedly on the ground weeping. He rose and said to the Patriarch “…for the multitude of my unmeasured trespasses, rightly and justly I am suffering.” During Leo’s last years he was humbly admitted as a penitent, which was a humiliation. It seems unlikely an Emperor chose this image for himself. There is a chance that Nicholas Mystikos, the Patriarch deposed by Leo, and his successor Alexander could have put it up. This is a case of the power of the Church prevailing over the Emperor, not unlike that of Ambrose of Milan and Theodosios the Great. This incident is immortalized by the Leo VI mosaic, which I have written more detail about if you click the link. Another example of the Church flexing it’s power, was when the Patriarch Polyeuktos forbade John Tzimiskes from entering the church. The Patriarch had deemed his assassination of Nikephoros Phokas to be sinful, and require John to atone for his sins first.

However, the Hagia Sophia was a place Emperors could connect with the people as well. Grand ceremonies could occur within the church, and the processions of the Emperor to the church could garner the attention of the people. When Basil I took power, according to the chronicler John Skylitzes “all the subjects of the Roman Empire rejoiced.” The Hagia Sophia gave the new emperor a great venue to gain the favor of the people of Constantinople and show off his generosity. Skylitzes added that Basil “went in public procession to the Great Church of the Wisdom of God and on the ay back he scattered a considerable amount of money to the crowd.”

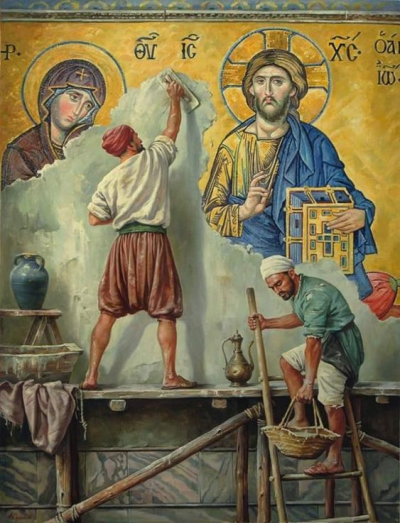

Many of the original Justinianic mosaics did not last through Byzantine times due to Iconoclasm, earthquakes, and renovations. Emperor Leo III made the decision to ban religious icons in 726 which removed all icons from Hagia Sophia. It was damaged by fire in 859 and in 869 by an earthquake. A third major earthquake occrred in 989. Part of the dome collapsed at that time. Basil II looked to an Armenian architect named Trdat to repair it, which he did. He was the best contemporary Armenian architect, and clearly convinced Basil he was the best man for the job. Most of the surviving mosaics are from after the end of iconoclasm. The oldest mosaic is that of the Theotokos and the infant Christ. It is from the 9th century, part of the triumphant return of icons. It has a damaged inscription near it that says ‘’The images which impostors cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” Other mosaics were added in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. The Church also had been, since the times of Justinian and Herakleios, filled with gold and silver, much of which survived iconoclasm. In 1028, Romanos III had the column capitals of Hagia Sophia decorated with gold leaf. The church had hundreds of chalices and holy vessels which even Heraclius spared during his search for cash, out of piety. It also had gold and silver jewel encrusted cases for icons.

“RIVERS” ON THE FLOOR OF HAGIA SOPHIA:

Of course I am referring to the ancient stone floors, not the present carpet which is installed in the building. Which, in my opinion was a poorly chosen carpet on aesthetic grounds for a Turkish culture known for such high quality exquisite rugs. The floors are really amazing, of course the greatest part is the Omphalion, but there is other great stonework to be seen. The original floors have even been described as “Marble Rivers” in some sources.

George Majeska wrote about how Paul the Silentiary described the pulpit of the Great Church as standing as “a beautiful island amidst the swelling billows …[which yet] does not stand in the middle space completely cut off, like an island girdled by the sea; it is rather like some wave-washed land, projected forward by an isthmus into the middle of the sea through the grey billows… it projects into the ocean…wave washed on either side…” Majeska added that in other primary sources, the nave was referred to as a depiction of the earth in marble form. There was “green [marble] in the likeness of rivers flowing into the sea,” and there were “four green rivers representing the rivers which flowed from paradise.” There are still large pieces of these “rivers” though large sections are gone due to damage and repairs.

THE LAST YEARS UNBLEMISHED:

The Hagia Sophia’s importance did not diminish even as chaos took over the Empire after the death of Manuel Komnenos. A great drama unfolded as Alexios Angelos became Emperor of the Romans in 1195, less than ten years before the fall of the city to the Crusaders. A crucial primary source, Niketas Choniates, said that Alexios Angelos had to seek approval of the people inside Hagia Sophia, but eventually “all those inside the Church [Hagia Sophia] consented to the new tyranny, and one of the sacristans, bought off by a few coins (the agitators from the marketplace and several judges, whose names I cannot bring myself to mention–followed suit), ascended the holy pulpit and began to chant Alexios’s acclamation without waiting for the chief shepherd’s signal. But the later, who resisted for a short time since the self-called [Alexios] had not made his appearance, hanged his mind about the previous Emperor [Isaakios]. When the Patriarch weakened, there was no one left to offer resistance.”

Choniates details his coronation and claims that there was a sign of the impending doom of the Empire as he left Hagia Sophia after being crowned: “When Alexios entered the celebrated Great Church of the Wisdom of God so that according to custom he might be anointed with the insignia of sovereignty, the first thing he did was to sign the symbol of the faith in imperial ink. Afterwards he approached the so-called Beautiful Portals of the temple, and remained there for some time, awaiting to receive the signal for the exact moment of his entrance [into the narthex] from the timekeepers in the Catechoumeneia above. When he had left the temple, and was about to mount his horse, which was led forward by the reins by the prostrator [Manuel Kamytzes], an unusual and wondrous event took place. The horse, its eyes blood red and ears erect, snorted, and bounded about spiritedly; driven wild with rage against him, it shunned Alexios as though it disdained to carry him on his back. Alexios made repeated attempts to mount the horse, but, kicking up its front hooves and wheeling about, it repulsed him. After much coaxing, it finally seemed to calm down, to cease making its proud gyrations and thrashing its legs in the air. The Emperor leaped on it and grabbed the reins, but the horse, as though it was tricked into accepting the rider against its will, misbehaved as before, lifting up its legs and neighing loudly. Nor did it end its Bacchic frenzy until it had knocked the bejeweled crown from the Emperor’s head to the ground so that certain parts of it were shattered and had thrown him off like a ball as well. When another horse was brought forward and Alexios paraded with a broken crown, this was deemed an inauspicious portent of the future: that he would be unable to preserve the Empire intact but would fall from his lofty throne and be ill-treated by his enemies.” It sounds like a sign, but it is important to note that Choniates wrote with hindsight, not foresight, of the sack of Constantinople. It comes across to me that he worked his way back from 1204 and determined this is where the Empire took a turn it could not come back from, and wanted to be on the right side of history.

In the year 1200, the last recorded foreign visit to Constantinople with good detail prior to the Fourth Crusade. St Anthony of Novgorod described countless relics and treasures of Hagia Sophia which were soon to be hauled west for Latin churches or melted for coins. One thing he mentions is: “In the sanctuary is likewise preserved the real chariot of Constantine and Helena, made of silver; there are gold plates, enriched with pearls and little jewels, and numerous others of silver, which are used for the services on Sundays and feast days: there is water also in the sanctuary coming out of a well by pipes.” This wealth was astonishing, keep in mind that by the 14th century the Byzantines will be so poor even the Emperor will not have gold plates. Hagia Sophia had accumulated so much by 1200, it was essentially a museum of the greatest Christian relics and art. “Above the great altar in the middle is hung the crown of the Emperor Constantine, set with precious stones and pearls. Below it is a golden cross, which overhangs a golden dove. The crowns of the other emperors are hung around the ciborium, which is entirely made of silver and gold. Thus the altar pillars and the sanctuary and the bema are built of gold and silver, ingeniously made, and very costly. From the same ciborium hang thirty smaller crowns, as a remembrance to Christians of the pieces of money of Judas.” This all came crashing down in 1204 as the crusader soldiers poured inside Hagia Sophia with an excitement for gold, not God, in the hearts.

Anthony of Novgorod is also a useful source for the elaborate ceremony which took place during worship in the Great Church. “When they sing Lauds at Hagia Sophia, they sing first in the narthex before the royal doors; then they enter and sing in the middle of the church; then the gates of Paradise are opened and they sing a third time before the altar. On Sundays and feast days the Patriarch assists at Lauds and at the Liturgy; at this time he blesses the singers from the gallery, and ceasing to sing, they proclaim the polychronia; then they begin to sing again as harmoniously and as sweetly as the angels, and they sing in this fashion until the Liturgy. After Lauds they put off their vestments and go out to receive the blessing of the Patriarch; then the preliminary lessons are read in the ambo; when these are over the Liturgy begins, and at the end of the service the chief priest recites the so-called prayer of the ambo within the sanctuary while the second priest recites it in the church, beyond the ambo; when they have finished the prayer, both bless the people. Vespers are said in the same fashion, beginning at an early hour.”

Robert De Clari, a crusader historian who documented the Fourth Crusade, wrote that after seizing Constantinople, the Crusaders realized just how magnificent and splendid the city and Hagia Sophia really were. They “regarded the great size of the city, and the palaces and fine abbeys and churches and the great wonders which were in the city, and they marveled are it greatly. And they marveled greatly at the church of Saint Sophia and at the riches which were in it…The master alter of the church was so rich that it was beyond price, for the table of the altar was made of gold and precious stones broken up and crushed all together, which a rich emperor had had made. This table was fully fourteen feet long. Around the altar were columns of silver supporting a canopy over the altar which was made just like a church spire, and it was all of solid silver and was so rich that no one could tell the money it was worth. The place where they read the gospel was so fair and noble that we could not describe to you how it was made. Then down through the church there hung fully a hundred chandeliers, and there was not one that did not hang by a great silver chain as thick as a man’s arm…there was not a chandelier that was not worth at least 200 marks of silver.” This description was shortly before this great wealth which he documented was scoured for every ounce of treasure the crusaders could get their hands on.

THE TRAGEDY OF THE FOURTH CRUSADE (1204-1261):

The Fourth Crusade would be the end of Hagia Sophia’s unparalleled interior splendor and riches. When the Crusaders came to the city and held it ransom, the abominable Byzantine Emperors Isaac II and Alexios IV Angelos shamefully stripped away the famous hanging silver oil lamps and most of its gold decorative elements. They then gave this money to the crusaders, who said it was not enough and attacked and destroyed Constantinople anyway. Perhaps this money could have saved the city if used to pay for its defense instead of pay its conquerors. My guess is the Crusaders saw this treasure, and realized there had to be a lot more and that it only increased their determination to sack the city at any cost.

The Crusaders set fires some of which almost burned the Church down during their siege, and after great damage they took control of the city and set out to any sources of wealth they could find. The palaces and the Hagias Sophia were the number one targets. When the crusaders entered the Hagia Sophia they systematically violated it as they methodically stripped its wealth. It said by Niketas Choniates the Latins brought donkeys inside Hagia Sophia, and used them to pull down the massive silver panels which decorated parts of the church. The altar was recorded to have been smashed to pieces and handed out as loot for the western soldiers, who despite once swearing an oath to go to Jerusalem to fight “for God,” found themselves destroying the largest Christian city and plundering the largest Christian Church. The crusaders allegedly took 40 chalices from just the altar of Hagia Sophia. The wondrous 50 foot high silver iconostasis was destroyed by the crusaders, who felt no sin destroying such pious artifacts. Until the liberation of Constantinople in 1261 the Church was damaged from the looting, and became a Catholic cathedral. The Venetian Doge Dandalo, a mastermind of the attack was unfortunately buried here, until 1453 when his bones were thrown to the dogs by Ottoman soldiers looting the Hagia Sophia.

Choniates was livid describing the destruction of the Roman’s prized churches, particularly the Hagia Sophia: “How shall I begin to tell of the deeds wrought by these nefarious men! Alas, the images, which ought to have been adored, were trodden under foot! Alas, the relics of the holy martyrs were thrown into unclean places! Then was seen what one shudders to hear, namely, the divine body and blood of Christ was spilled upon the ground or thrown about. They snatched the precious reliquaries, thrust into their bosoms the ornaments which these contained, and used the broken remnants for pans and drinking cups,-precursors of Anti-Christ, authors and heralds of his nefarious deeds which we momentarily expect. Manifestly, indeed, by that race then, just as formerly, Christ was robbed and insulted and His garments were divided by lot; only one thing was lacking, that His side, pierced by a spear, should pour rivers of divine blood on the ground.

Nor can the violation of the Great Church [note: Hagia Sophia] be listened to with equanimity. For the sacred altar, formed of all kinds of precious materials and admired by the whole world, was broken into bits and distributed among the soldiers, as was all the other sacred wealth of so great and infinite splendor.

When the sacred vases and utensils of unsurpassable art and grace and rare material, and the fine silver, wrought with gold, which encircled the screen of the tribunal and the ambo, of admirable workmanship, and the door and many other ornaments, were to be borne away as booty, mules and saddled horses were led to the very sanctuary of the temple. Some of these which were unable to keep their footing on the splendid and slippery pavement, were stabbed when they fell, so that the sacred pavement was polluted with blood and filth.

Nay more, a certain harlot, a sharer in their guilt, a minister of the furies, a servant of the demons, a worker of incantations and poisonings, insulting Christ, sat in the patriarch’s seat, singing an obscene song and dancing frequently. Nor, indeed, were these crimes committed and others left undone, on the ground that these were of lesser guilt, the others of greater. But with one consent all the most heinous sins and crimes were committed by all with equal zeal. Could those, who showed so great madness against God Himself, have spared the honorable matrons and maidens or the virgins consecrated to God?

Nothing was more difficult and laborious than to soften by prayers, to render benevolent, these wrathful barbarians, vomiting forth bile at every unpleasing word, so that nothing failed to inflame their fury. Whoever attempted it was derided as insane and a man of intemperate language. Often they drew their daggers against any one who opposed them at all or hindered their demands.

No one was without a share in the grief. In the alleys, in the streets, in the temples, complaints, weeping, lamentations, grief, the groaning of men, the shrieks of women, wounds, rape, captivity, the separation of those most closely united. Nobles wandered about ignominiously, those of venerable age in tears, the rich in poverty. Thus it was in the streets, on the corners, in the temple, in the dens, for no place remained unassailed or defended the suppliants. All places everywhere were filled full of all kinds of crime. Oh, immortal God, how great the afflictions of the men, bow great the distress!”

These are terrible scenes. Robert De Clari had described the wealth similarly to Choniates, but less in reverence and more like the way a predator eyes its prey. Hagia Sophia had been adored with imperial patronage, the wealth of the Church, donations, and had accumulated unbelievable wealth. Now, it was simply being divided amongst barbarians.

HAGIA SOPHIA LIBERATED (1261-1453):

When Michael VIII Palaiologos entered the freshly liberated Queen of Cities in 1261 he would have seen that the entire city needed massive work. Large parts of the city were sparsely populated ruins, many churches had been robbed of their splendor, the Great Palace was in a terrible state. Although the Hagia Sophia was to be finally handled with respect and care again after 57 years of neglect and robbery, much was lost that would never to be returned. For example, writing in the 15th century over two hundred years after Anthony of Novgorod had recorded the rituals which occurred in Hagia Sophia, Symeon the Archbishop of Thessaloniki wrote about the changes which had occurred. According to Oliver Strun he “included in his monumental treatise On Divine Prayer, an elaborate exposition of the ceremonies that the Russian pilgrim had witnessed, together with a minute analysis of the differences between the liturgical practices of the Great Church and those of the monasteries. But by this time, the situation throughout the Empire had deteriorated to such an extent that these practices, once the glory of Hagia Sophia and the other great churches, had largely fallen into disuse.”

The Archbishop Symeon blamed the the Latin Crusaders and their conquest of Constantinople for the loss of ceremony in the Great Church:

“After Constantinople had been enslaved [he says], and the clergy driven out and settled elsewhere, these ceremonies were neglected; it became customary not to perform them, and when the clergy returned after many years, their practice ceased; from the one church [Hagia Sophia], as from a mother, this was handed on to the rest.”

However, despite some loss of cultural heritage, Orthodox rituals were returned to the Hagia Sophia and once again it became the principal church of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

The Deesis mosaic was part of these renovations of the 13th century. However this was last time the Emperors had major resources to lavish on Hagia Sophia. Andronikos II had to use his wife’s inheritance to pay for new buttresses to reinforce and repair the structure. In 1344 a major earthquake caused parts of Hagia Sophia to collapse by 1346 on the western side. The repairs took 8 years.

A western account of visiting Hagia Sophia is Petro Tafur in 1437. He described the building as being in splendid condition despite the fact that the Byzantine state was impoverished by that time. Probably the wealth of the Church itself, not the Emperor, sustained that condition. I found this account on a website called pallasweb, pretty interesting:

“On the day following I went to the Despot (Constantine XI), and asked him if he would be pleased to direct that I should be shown the church of St. Sophia and its relics, and he replied that he would do it with pleasure, and that he himself desired to go there to hear Mass, as did also the Empress and her brother, the real Emperor of Trebizond. We then went to the church to Mass, and afterwards they caused the church to be shown to me. It is very large and they say that in the days of the prosperity of Constantinople there were in it six thousand clergy. Inside, the circuit is for the most part badly kept, but the church itself is in such fine state that it seems to-day to have only just been finished. It is made in the Greek manner with many lofty chapels, roofed with lead, and inside there is a profusion of mosaic work to a spear’s length from the ground. This mosaic work is so fine that not even a brush could attempt to better it. Below are very delicate stones, intermixed with marble, porphyry, and jasper, very richly worked The floor is made of great stones; most delicately cut, which are very magnificent. In the center of these chapels is the principal one which is very large; the height is such that it is difficult to believe that cement can hold it together. In this chapel there is similar mosaic work, with a figure of God the Father in the center.”

THE LAST DAYS (1453):

At some point during the final siege of Constantinople by the Ottomans, it became apparent that the Ottomans were likely to win. That is because Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos had sent out scouts to check for the Venetian reinforcements he had been expected, and they were nowhere to be found In the words of Donald M. Nicol “the whole of Christendom, it seems, had deserted him in his fight against the enemies of the Cross. He committed himself and his city to the mercy of Christ, His Mother, and the first Christian Emperor, the holy Constantine the Great.”

Despite the hostility between Latin and Orthodox clergy, the two joined together in the Great Church to pray and beg God for their salvation. Constantine was very spiritual in his final days, having the best icons of the Romans paraded through the streets of Constantinople. Constantine finally went to the Hagia Sophia to “pray and ask forgiveness and remission of his sins from every bishop present before receiving communion at the altar. The priest who gave the sacrament could not have known that he was administering the last rites” to the last ever Roman Emperor. Nor could they have known that it was the last time a Roman Emperor would step in the Great Church. Constantine then “went back to his palace at Blachernai to ask for forgiveness from his household and bid them farewell before riding into the night to make a final inspection of his soldiers at the wall.”

THE FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE AND THE SECOND PILLAGING:

The conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque began on May 29, 1453 soon after the the Ottomans conquered the city. As soon as Ottoman soldiers entered Constantinople it was a main target for the riches it held. The contemporary historian Doukas wrote: After the city begin to fall “a great horde of mounted infidels (Turks) charged down the street leading to the Great Church (Hagia Sophia). The actions of both Turks and Romans made for quite a spectacle. In the early dawn, as Turks poured into the City and the citizens took flight, some of the fleeing Romans managed to reach their homes and rescue their children and wives. As they moved, bloodstained across the Forum of the Bull and passed the Column of the Cross [Column of Constantine in the Forum of Constantine], their wives asked ‘What is to become of us?’ When they heard the fearful cry ‘The Turks are slaughtering Romans within the City’s walls,’ they did not believe it at first. They cursed the messenger instead. But behind came a second, and then a third, and all were covered in blood, and they knew that the cup of the Lord’s wrath had touched their lips. Monks and nuns, therefore, men and women, carrying their infants in their arms and abandoning their homes to anyone who wished to break in, ran to the Great Church [Hagia Sophia]. The thoroughfare, overflowing with people, was a sight to behold!”

Doukas added: “Pillaging, slaughtering, and taking captives on the way, the Turks reached the temple [Hagia Sophia] before the termination of the first hour. The gates were barred, but they broke them with axes. They entered with swords flashing and, beholding the myriad populace, each Turk caught and bound his own captive. There was no one who resisted or who did not surrender himself like a sheep.” Hagia Sophia, arguably was the last place within Constantinople to fall that day. With it, any hope of salvation was gone as those who believed in it were enslaved within it.

As Doukas narrated, the defenses along the Theodosian walls failed, and Ottoman soldiers poured into the city looking for spoils of war. They thought Hagia Sophia would have the most valuables. They were likely disappointed – due to the weakness of Byzantium and the loss of wealth during the Fourth Crusade, the Turks found relatively little precious metals there. It was nothing like what the Latins had found in their sacking of the city.

They did find value in the people themselves though. Refugees from across the city were huddled inside its greatest church, aware the defenses had fallen, and likely in great fear. Of course the Ottoman soldiers busted down the locked doors, and then sorted everyone inside by value for enslavement. The sick and wounded were killed. An imam shouted the shahada and said something like ”there is no god but Allah and Muhammad is his messenger. “ From that moment on, Hagia Sophia would never be a church again. The Greek clergy stubbornly continued their Divine Liturgy even as Turkish soldiers stormed in until they were forcibly stopped. This was the end of Orthodoxy in the great church.

Sultan Mehmed II ordered Hagia Sophia converted into his new capital’s first Imperial mosque, and stopped his soldiers who were damaging the building, as it was his property not theirs. The mosaics were mostly left uncovered in Hagia Sophia during this time, and as late as 1498 the original floor was still mostly visible before being fully carpeted. The first minaret was built by 1481. Many mosaics were covered during the reign of Sultan Suleiman. The building continued to be modified, restored, and renovated during Ottoman times.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF HAGIA SOPHIA:

The Ayasofya began a new life after the conquest of Constantinople as an Ottoman imperial mosque. Bayazid was present at Constantinople in 1422 when his father Murad II was laying siege to the city, and could see the massive domed church from a distance. He dreamed of converting it to be a mosque. Although the Theodosian walls prevented that then, in 1453 it could come to be. This was a long-term goal of Islamic armies, I am sure the Arabs during the siege of 717 dreamed of it when their army saw it while camped in the same spot outside of the Roman capital.

Although for the majority of it’s history it was the Great Church of the Roman capital of Constantinople, it has had a new journey since the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. In Ottoman Constantinople, it was an imperial mosque, and a symbol, perhaps even a trophy, of the triumph of the Ottomans over the Romans. Converting the greatest Church in the world at the time of it’s conquest into a mosque was a hugely symbolic and powerful move for Mehmet. And the Ottomans used it and maintained it themselves. Turkish historian Gulru Necipoglu described “the unusual resilience of the original sixth-century structure despite numerious later additions and changes” as a “tribute to Justinian and his architects, whose daring experiment in dome construction remained an unsurpassed feat for many centuries. Hagia Sophia’s successive adjustment to modified circumstances and its capacity to absorb change while remaining essentially unchanged was due largely to an uninterrupted recognition of its unique formal qualities and its rich aura of symbolic associations through the centuries.”

When Mehmed entered the city he was well aware of it’s prestige and significance. The Ottoman historian Tursan Beg, a contemporary of Mehmed and member of his court, described Mehmet went through “the ‘paradise-like’ Hagia Sophia with a group of learned men and dignataries, contemplating the vastness of its ‘celestial dome,’ its patterned marble floors resembling the wavy sea, and its artistic gold mosaics.” Only after thoroughly inspecting it and admiring it’s magnificence did the Sultan order the repairs which the Byzantines could not afford in their last days.

Although for some Byzantophiles and Orthodox Christians, the transformation of Hagia Sophia into a mosque is saddening, it is an important part of the long history of the monument. Gulru Necipoglu said “the various stages in the formal transformation and Ottomanization/Islamization of the post-Byzantine Hagia Sophia constitute an integral part of the monument’s history. The layers of meaning the building acquired over the centuries transcended the specificity of the original context in which it was created and the chronological slot it occupies in the diachronic sequence of architectural history.” I think that today part of what makes the Hagia Sophia/Ayasofya so intriguing is dual significance to both Christians and Muslims. It’s continuous use also helped the building survive intact, as maintaining it requires costly repairs over the centuries.

Hagia Sophia Today: From Museum to Mosque:

The famous Hagia Sophia museum, a site tourists flocked to in Istanbul – originally founded as the greatest church in the world by the Emperor Justinian – has been turned back into a mosque since 2020.

“Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced the decision after a court annulled the site’s museum status. Built 1,500 years ago as an Orthodox Christian cathedral, Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest in 1453. In 1934 it became a museum and is now a Unesco World Heritage site.” But, in 2020 the museum status which had been bestowed upon it by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, was removed by Erdogan.

My hope is that one day Ayasofya Camii (Hagia Sophia Mosque) will one day again become the Hagia Sophia Museum for all people to enjoy, as international monument for people to enjoy as it was before 2020.

That said, I will one day go to Istanbul and visit the Hagia Sophia, whether it is a mosque or not, and I will try to enjoy the experience of seeing what was once upon a time the Great Church of Constantinople with my own eyes.

Sources:

http://spot.pcc.edu/~rflynn/HST_101/Online%20Readings/Procopius_Buildings.html

The Bronze Horseman of Justinian in Constantinople: the Cross-Cultural Biography of a Mediterranean Monument by Elena Boeck https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/bronze-horseman-of-justinian-in-constantinople/C283B094DEBB9F5BC531F53BE6FA5CF7

Niketas Choniates – O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniates. Translated by Harry Magoulias. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984.

The Name of the Church of St. Sophia in Constantinople, by Glanville Downey. Harvard Theological Review / Volume 52 / Issue 01 / January 1959

Archaeology of St. Sophia at Constantinople: The Green Marble Bands on the Floor by George P. Majeska. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 32 (1978)

Advanced Byzantine cement based composites resisting earthquake stresses: the crushed brickylime mortars of Justinian’s Hagia Sophia by A. Moropoulou, A.S. Cakmak , G. Biscontin , A. Bakolas , E. Zendri

The Byzantine Office at Hagia Sophia by Oliver Strun. Dumbarton Oaks Papers (1956)

Investigations into the construction and repair history of the Hagia Sophia by Fritz Wenzel (2010)

The Making of Hagia Sophia and the Last Pagans of New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis. Journal of Late Antiquity, Volume 6, No.2, 2013.

Master Builders of Byzantium, Robert Ousterhout

Hagia Sophia From the Age of Justinian to the Present. The Life of An Imperial Monument: Hagia Sophia After Byzantium by Gulru Necipoglu

The Immortal Emperor, Donald M. Nicol

A Spectrum of Unfreedom: Captives and Slaves in the Ottoman Empire, Leslie Peirce