The Column of Justinian was among the greatest monuments of Constantinople, it was likely the highest monument one would see when approaching Constantinople. It was the likely on of the tallest features of the skyline of Constantinople which one would first see when approaching the city, along with the nearby Hagia Sophia. It was one of many Roman triumphal columns in Constantinople – others were those of Constantine, Leo, Theodosius, Arcadius, and Marcian. Arguably, the Column of Justinian was the greatest Roman column in the city. The only rival to its grandeur was Constantine’s majestic porphyry column, which was symbolically more important than Justinian’s column. I put on my list of 7 Byzantine Wonders of the World – I feel because there is nothing left of it that it is not as remembered as it should be!

THE AUGUSTAION:

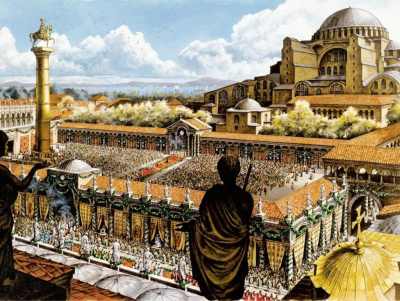

The Augustaion was an enclosed area, kind of like a private forum, south of the Hagia Sophia. The Augustaion is said to have been first created by Constantine the Great, who put a statue of his mother Saint Helena there upon a column. But the Augustaion was changed a couple times after that, first in 459 and then during the 6th century during the reign of Justinian who built the Hagia Sophia. It became like a private courtyard of the Hagia Sophia, and remained a feature of the city throughout Byzantine history.

The Augustaion was home to several monuments other than its crown jewel which was Justinian’s massive column. There were three statues which depicted barbarian kings in front of Justinian’s column, with an obvious message of the great power and respect which Justinian wanted to convey. There was also the Senate House there, for the senate of Constantinople which Constantine had founded for his New Rome. The building was on the eastern side of the Augustaion, and it had been constructed during the reign of Constantine or Julian the Apostate. It did not last long before being damaged by fire in 404, before being totally destroyed in 532 during the Nika Riots when it was burned down. This prompted Justinian to rebuild the Augustaion, and lavish it with monuments intended to glorify him for eternity.

THE WILL OF JUSTINIAN:

In fact, I would say that it is a testament to the will of Justinian to make a grand monument in an era where such things were fading away. By the 6th century, the Romans were no longer making as many statues and the quality was declining as well. Sarah Bassett wrote in The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople that: “For all of the respect accorded to classical tradition, however, it was evident by the end of the sixth century that the past and the ways in which it legitimated people and places was being redefined. The general decline in the use of public sculpture, ancient or contemporary, together with the willingness to dismantle collections like the Augusteion gathering, indicate that antiquities, the defining heart and soul of Constantinian and Theodosian capital, were no longer the dominant visual currency.” We should appreciate that Justinian was able to make this epic column in an era where such things were fading away.

The public spaces were very crowded in Constantinople by the age of Justinian. To create a monument like this meant to compete with your dead predecessors. To be remembered, Justinian had to make a monument which was unique and greater than the other Emperors before him. The Nika Riots burning down the Augustaion and allowing him to remodel it as a testament to his own glory gave him a place to do that. Instead of building a forum, which would have been harder, he attached his column to the Augustaion courtyard, which was itself attached to the Hagia Sophia. Justinian had made the two highest monuments of the city, a monumental duo which could never be outdone.

CONSTRUCTION:

The Column of Justinian was completed in 543 AD, well after the Hagia Sophia which had been finished in 537.

THE GREATEST COLUMN?:

Elena Boeck, one of the biggest experts in the world on this topic, says in her introduction that “Justinian’s triumphal column was the tallest freestanding column of the premodern world and was crowned with the arguably the largest metal equestrian sculpture created anywhere in the world before 1699.” This is not just another typical Roman column. It was very unique its ambition and design, and it was an “urban icon” in the Queen of Cities.

When it comes to size, it was the largest column in Constantinople. Constantine’s column was probably around 40 meters tall, where as the column of Justinian was probably 50+ meters. The only rival in terms of size was the Column of Theodosius.

This monument was extremely significant to contemporary Romans, even very late in Byzantine history.

THE STATUE OF JUSTINIAN:

Justinian was the only Emperor to put an equestrian statue on top of their column. The statue was originally one which depicted Emperor Theodosius the Great. When the statue was taken down by the Ottomans this would have been apparent due to the markings on it which still bore the inscriptions of his name. However, it was modified a bit and reused for Justinian. However, this should not take anything away from the grandeur of the monument.

Justinian saw his predecessors columns and thought he would outdo them yet. In fact, making such an impression took great calculation. The public spaces were already crowned

It should not be forgotten just how much of an engineering accomplishment getting that heavy statue on top of the column was. Bertrandon de la Broquiere visited in 1432 and wondered: “I have no idea how the statue was put up there, given its size and weight.“

In the left hand of the statue, the mighty Emperor held the globus cruciger, which was the symbol of imperial domination over the world – with a cross added to imply divine sanction for that. George Pachymeres, writing in the 13th century said of it: “for the apple(sphere) represents the world and it is by the power of the cross that he, the master of the whole earth, has been emboldened to grasp it.”

The statue was a potent symbol of Roman imperial authority in Constantinople. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, after finishing the long arc of Roman history on May 29, 1453 – had the statue removed from atop its mighty column fairly soon afterwards. However, he must have admired Justinian’s equestrian colossus for he kept it in the grounds of Topkapi palace. This is how we have a reasonable idea of how it looked, thanks to the drawings recorded by visitors.

SURVIVING THE FOURTH CRUSADE:

(coming soon)

DROPPING THE BALL:

After the Fourth Crusade, what was left of the Column of Justinian was important and even the relatively impoverished Palaiologan emperors spent resources to maintain the monument. Time was taking its toll, in the 13th century it was recorded that some of the feathers of Justinian’s toupha (his headgear) had fallen. The Romans were so poor, that the Emperor had to use inheritance from his deceased wife’s estate. The funds which did not go directly to their children were used to repair both the Hagia Sophia and the Column. It is a testimony to how much Emperors struggled, without private funds the two greatest monuments of Constantinople could not be repaired.

Andronikos II, the son and successor of Michael VIII, restored this monument in 1317. Elena Boeck explained the significance of it in her book: “The Bronze horseman had issued an ominous warning in 1317. The fall of the horseman’s orb caused grave concerns for the emperor Andronikos II. Yet Byzantine sources are silent about this important event. A range of evidence suggests that the Byzantine historian Nikephoros Gregoras intentionally underplayed the incident. By protectively demurring about the object that had fallen – the symbol of (imperial) sovereignty and dominion – he concealed contemporary anxieties behind a rhetorical facade of successful restoration. The horseman’s insecure grasp of the orb and the orbs inexplicable mobility became a flash point for international concerns about the future of Byzantium.”

One can see from Boeck’s writing that this orb was not just a piece of art. It was the symbol of the Roman Empire at this point. She pointed out that peoples from as afar away as England, Spain, and Russia were concerned about the globus cruciger in Justinian’s hand. The symbolism of the orb went hand in hand with challenges and tragedies of Byzantine society, weakened security, and the territorial decline of their civilization at the time.

Gregoras said “…it so happened that from strong gusts of northern wind a copper cross fell down, which had been in the hand of the statue, which stood on the column, which stood on the square of the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom. The emperor ordered the cross to be restored to its original place with utmost haste.” Boeck says that Gregoras was simplifying the matter by not elaborating on its symbolic significance. The globus cruciger implied that the Roman Emperors ruled over the world, only with the backing of God. The orb represented the earth in the hand of the Emperor, but the cross on top made it clear that power came from God.

The repairs were actually rather challenging though. Imagine all the carpenters and laborers required to install and craft the necessary materials. To make such tall scaffolding which multiple men could climb meant it had to be very securely constructed. Gregoras described the woodworks needed to reach Justinian atop his tall column: “Having surrounded the entire column with wooden scaffolding, they reached the sculpture proper. The craftsmen, having reached it using the scaffolding.” Very few people in history actually saw the statue up close like that. Possibly the first time anyone had been to the top of the column since Theophilos who ruled in the 9th century. Though, personally, I wonder if the Latins had been up there during their operations to rip the bronze plates off the column – but who knows.

The problems for the statue were magnified once workers had reached it. Gregoras wrote that “The craftsmen … found that the entire iron [support structure], which was supporting the horse of the statue from both sides, was deeply corroded; therefore there was a real danger that at some point these supports would fall, and with them the entire statue would perish, this great marvel of the capital, which alone remained from the multitude of monuments which were like it and equal to it, having escaped the frenzy of fires and the greed of the Latins.” It makes sense, is not amazing that in the 14th century a statue from the 6th century still remained on top of its column at all? The coastal sea air is itself very corrosive.

So what had began as a simple repair job had become a full-fledged restoration – Gregoras again illuminates the process for us: “And so, instead of the older supports, [new ones] were secured under the horse, which were better and stronger, and upon which the statue leaned securely and firmly. Then, having taken off the head of the statue, the symbol of imperial greatness, and also the orb, which was positioned in the hand, [was covered] with more durable gilt and gave it more shine/luminosity. Then the entire column, the surface of which was full of holes from top to bottom due to the absence of nails in their proper places, which had been torn out by the Latins together with the copper, which had been covering the column, they covered with strong plaster and all of the indentations were covered and smoothed out.” The re-gilding of the orb and toupha would have become shining accent for the monument – a symbol of imperial authority shimmering in the sky once more.

But even these repairs did not last, a century later the statue had chains installed to tie the statue to its base. This shows that the repairs were not enough to halt deterioration. Perhaps even removing corroded areas exposed new areas to corrosion. The statue is best possible representation of the state of the Byzantine world at this time. An Empire which was becoming weaker by the day, increasingly frail but of symbolic importance, relying on the inheritance of the past for its grandeur.

FINAL OMEN:

(Coming soon)

CHANGING PERCEPTION:

The way the statue was seen throughout its 900 year history took on different meanings. I know I am quoting Elena Boeck a lot, but her words are just so well-crafted on this matter: “Over the course of centuries, the horseman served as a social agent that connected unrelated individuals. Even though it not mean the same thing to a Byzantine Emperor, Ottoman illustrator, English scribe, or a Russian traveler, their various engagements testify to its power of attraction. Individuals who otherwise had very little in common and who never visited Constantinople, such as the French poet Gautier d’Arras and the anonymous painter of a Russian icon, could both conceive of it as a kind of everlasting presence. The Palaiologan intellectual George Pachymeres could engage in an intense intertextual dialogue about the monument with his distant predecessor Prokopios. The French traveler Pierre Giles could do the same in the mid-sixteenth century.”

The reason I quoted that long paragraph was it just shows how this monument made people curious about it, it drew their attention, it inspired their imagination. It was a true wonder.

CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE:

(Coming soon)

SOURCES:

The Bronze Horseman of Justinian in Constantinople by Elena Boeck (I strongly recommend this book, its awesome)

The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople