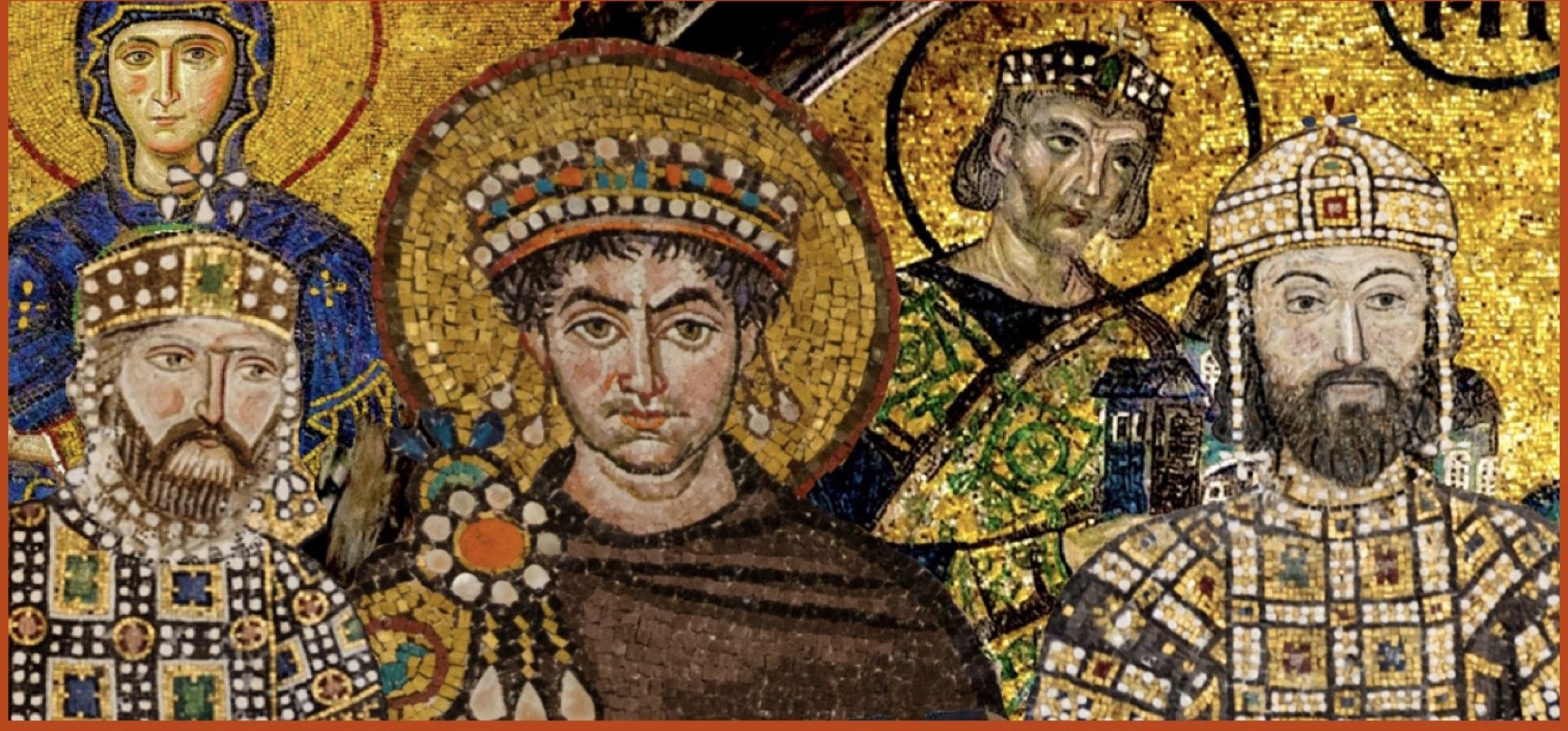

It seems that in the 21st century that it is generally far more accepted in the academic community that the “Byzantine” Empire is the direct continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire in the medieval period, lasting beyond the fall of the Western Roman Empire until conquest by the Ottoman Turks in 1453. However, some still consider that history irrelevant and though they acknowledge that continuity in a faint sense, they do not include them in their narratives to the correct extent. Thus it feels a little bit like “they are technically Roman, but not really Romans, just some roleplaying Greeks.” One could learn about the Middle Ages in a college class or highschool and have no idea who the Byzantines really are other than some “some guy named Alexius got the Crusades going by writing a letter to the Pope.”

Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire?

Which is it….both, I would say! The term Byzantine is a useful academic term, because what we think of the Byzantine Empire existed at a very different time and like any other civilization in history evolved considerably in the wake of those changes. My personal take is that there is nothing wrong with using the term Byzantine academically, but that the Roman identity must be reinforced in order to make sure that the term is not misleading or being used to deprive the Romans of their continuity.

There is a huge problem in that the Byzantines have been isolated from the story of European history. Writing in 1996, Robert Ousterhout described the ostracized status of Byzantium in the Western narrative of medieval history: “A session at the 1992 College Art Association was entitled The Byzantine and Islamic ‘Other’: Orientalism and Art History. Among many related issues, it examined the marginalization of Byzantine studies within the discipline of art history: Byzantium has become exoticized, isolated from Western European developments, and identified as the “Other.” In a provocative paper, Robert Nelson pointed out that no survey textbook presents the Byzantine period as contemporaneous with medieval Europe: Byzantium is either viewed as the end of Antiquity or as the beginning of the Dark Ages. Later Byzantine developments–those coeval with the Romanesque and Gothic styles of Western Europe are usually omitted, not fitting into a neatly encapsulated, linear view of European cultural history. Most textbooks simply stop with Hagia Sophia in Constantinople or with San Marco in Venice. But the separation of Byzantium from medieval Europe goes beyond the textbooks. Many medievalists are now of the opinion that Byzantine civilization is not a part of European history, thus justifying its complete omission from their teaching.” Ousterhout added a line I particularly love, scathing some of his colleagues by saying that he “often suspected that there was more interchange of ideas between Byzantium and the West during the Middle Ages than there is between scholars of the respective areas today.”

This is the problem, no one wants to put Byzantium in Middle Eastern or European history. It is just “other” to many. I think that overall Byzantium is being more included that it was in 1996, but the Eastern Romans deserve to maintain a strong presence in the narrative of Medieval Europe. Anything less is an injustice.

THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE IS THE ROMAN EMPIRE

There really is no convincing way to argue, unless one ignores some crucial facts, that the Byzantine Empire was a new state or just a “successor” to the Roman Empire. Until 1204 and the fracturing of the Byzantine state by the Crusaders, there is no event one could point to in order to claim there was a break in Roman history.

While it is absolutely fair to acknowledge that the Roman Empire changed a lot after Heraclius, it is intrinsically unfair to take to mean that it stopped being the Roman Empire. The Roman state and sense of cultural self-identity continued. Constantine moved the capital, ended the tetrarchy, and allowed for a new monotheistic religion to become mainstream. Does that mean the Empire changed as an entity then? No one would say that, but somehow Byzantium is not given the same consideration by some.

Here is an thought experiment. In 1776 the United States of America was only on the East Coast of North America, and was an agricultural slave holding society. It was made up of English colonies. Women could not vote, slaves were legally claimed to be only 3/5 of a person, etc. The culture has changed a lot, we are not British anymore, our dialect is different, we are more ethnically and geographically diverse. The modern country does not resemble the original hardly at all, does that mean it is not “really” the United States? But it is, and cultural evolution is normal. Humans are not static, and the Romans were no exception.

So not only was there no event to end continuity, but the Romans considered themselves to be Romans, and considering the facts back them up, who are we to question it? Do people say Egyptians are not Egyptians because they speak Arabic and are Muslim? The Egyptians have gone from pagan polytheists to Christians to Muslims since ancient times. But they are not robbed of their identity because ethnic identity is fluid and evolving. There is not a single ethnic group on earth that is the same as they were 2000 years ago. Religions, languages, names, and identities themselves are constantly changing.

I have heard ridiculous claims – for example, that the Empire did not have Rome so it was not Roman (and actually for a time it did hold Rome), but looking at history, Rome was not the capital for a long time. Milan and Ravenna had become the capitals of the Western Roman Empire, but there is no one claiming they were not really Romans. The Eastern and Western Roman Empire’s did not see themselves as being different civilizations. They were simply judicial halves of the same Empire governed in two units, just as the tetarchy had been 4 units. The Emperors Constantine the Great and Theodosius I, the last rulers to control the whole Empire ruled from Constantinople. They are universally seen as truly Roman. I have seen Justinian used as the last “truly Roman” ruler as well, just because he spoke Latin as his native tongue I suppose. But, there is no change after his death to find any lack of continuity, there is no special reason to consider him more uniquely “Roman.” Only by accepting and excluding information selectively, and using an inconsistent logical framework, can someone claim the Roman Empire ended in 476. But, people do. In order to fairly represent Byzantium in the narrative of our past, Roman continuity needs to be promoted and accepted more widely as fact.

SOURCES:

An Apologia for Byzantine Architecture, Robert Ousterhout

Romanland by Anthony Kaldellis