While describing the mausoleum of Justinian in the Book of Ceremonies, Constantine Porphyrogennitos described how how an imperial tomb was reused for the construction of he revetments of the Pharos chapel. The Porphyrogennitos wrote that “another sarcophagus, of Proconnesian stone, in which is laid Leo (III) the Isaurian; another sarcophagus, of green Thessalian stone, in which was laid Constantine (V), the son of the Isaurian, surnamed Kavallinos, but he was removed by Michael (III) and Theodora and his wretched body was burnt. Likewise, too, his sarcophagus was removed and sawn up and used in the construction of the Church of the Theotokos of the Pharos. Indeed, the large slabs which are in the said Church of the Pharos are from the said sarcophagus.“

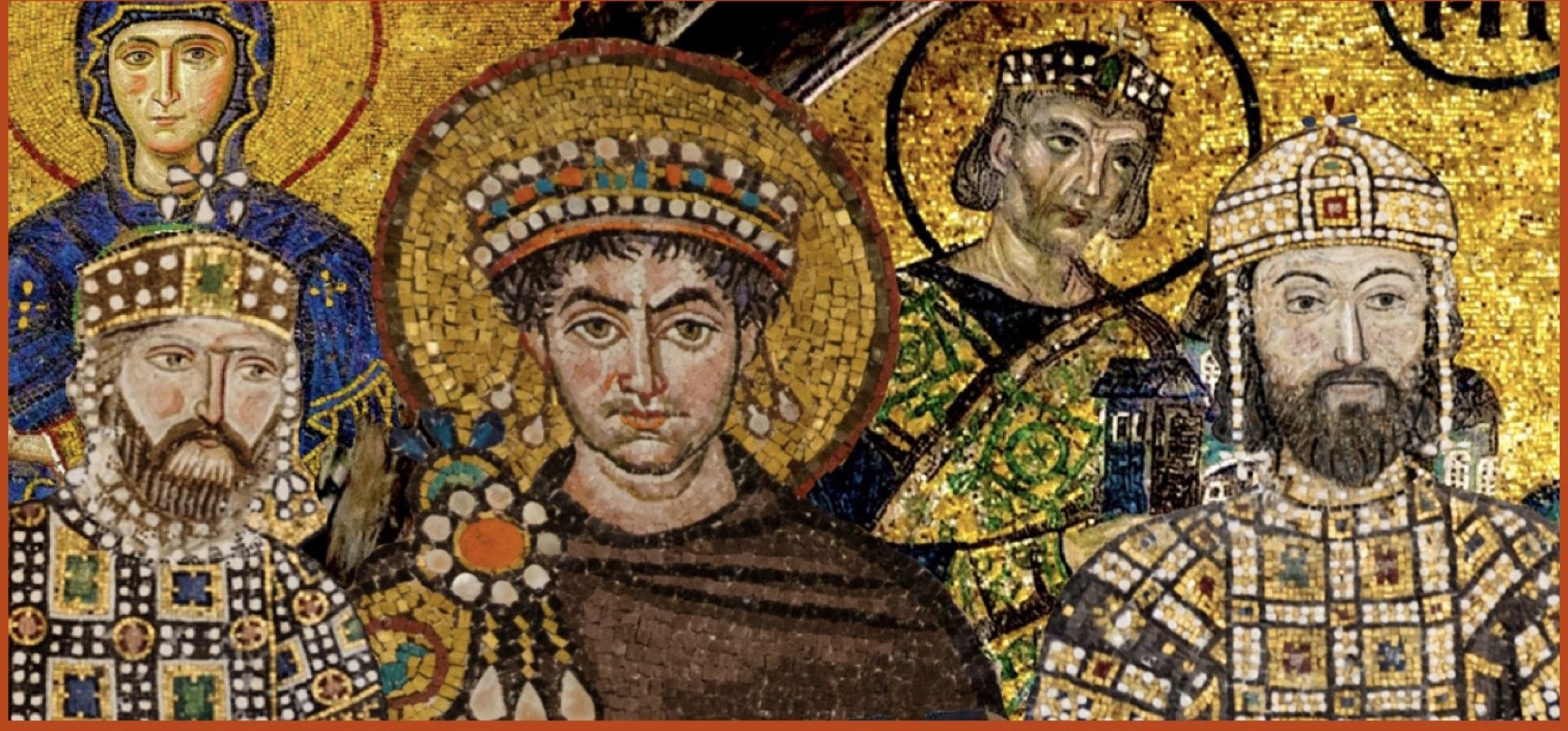

Annemarie Weyl Carr wrote in The Cambridge Companion to Constantinople about the “Mercati Anonymous, a late eleventh-century Latin translation from an earlier Greek original.” This text “presents a topographically ordered roster of sixty churches in Constantinople with their major relics and miracle stories. It must have been created and translated for the use of pilgrims to the city. A description of Jerusalem follows it, showing the two cities’ bond as pilgrimage destinations. Late Antique buildings – Hagia Sophia and Holy Apostles, St. John Stoudion, Sts. Sergius and Bacchus, the Marian churches of Chalkoprateia and Blachernai, the Hippodrome, the columns of Justinian (527–565) and Constantine – are joined by brilliant new ones – the palace churches of the Nea and St. Mary of the Pharos, Leo VI’s (870–912) St. Lazarus, Romanos III’s (1028–34) Peribleptos, Constantine IX’s (1042–55) St. George Mangana, the Hodegon with its great Lucan icon.”

However, Carr points out that it is important to note that “the text opens with St. Mary of the Pharos, home of the Passion relics. It lists forty-eight relics, a quarter of its total number and double those in Hagia Sophia. Twenty were relics of Christ, including the Mandylion, Kerameion, and Christ’s letter to Abgar. The Pharos’ relics represented three centuries of calculated imperial acquisition. Gained especially during the tenth-century wars of expansion, they were intended to consolidate and consecrate realm and rulers alike as a city and people of God.” The Pharos was not a massive church like Hagia Sophia, but it had over double the relics of Hagia Sophia. This Church seems, in my interpretation of what the average Byzantine enthusiast would think, to be the least well-remembered Byzantine church in comparison to it’s importance. This is the Church which an Emperor would bring a foreign leader to truly impress them and show them that the Romans were God’s true Empire.

Speaking of the Pharos, Robert De Clari wrote: “there was one of them called the Holy Chapel, which was so rich and noble that there was not a hinge nor a band nor any other part such as is usually made of iron that was not all of silver, and there was no column that was not of jasper or porphyry or some other rich precious stone. And the pavement of this chapel was of a white marble so smooth and clear that it seemed to be of crystal, and this chapel was so rich and so noble that no one could ever tell you its great beauty and nobility.” Part of the reason that this church is less famous today than it should be is because of what transpired there during and after the Fourth Crusade. The great relics of Pharos, the prized relics of the Constantinople, were taken, never to return. The wealth of the chapel was stripped bare, and it fell into disrepair. The Pharos was never even used following the Roman liberation in 1261, clearly it did not survive the period of Latin occupation intact. I would not be surprised if some of its columns are on Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice, or in an Ottoman mosque.

SOURCES:

The Book of Ceremonies written by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennitos

The Conquest of Constantinople by Robert De Clari

The Cambridge Companion to Constantinople, Edited by Sarah Bassett