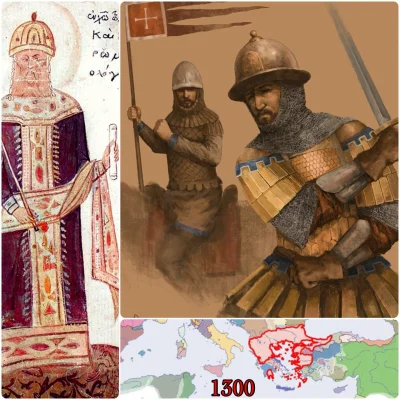

BACKGROUND: ANATOLIA DISINTEGRATING

The beginnings of the loss of Roman Anatolia in the 13th century was far from inevitable. Andronikos II Palaiologos bears the most responsibility. When a successful general won battles, they were removed! First, in a trip to Anatolia to deal with the increasingly bad conditions there, he removed two of the most important men in the defenses. “Andronikos arrested his own capable brother(Constantine Palaiologos), the porphyrogennetos Konstantinos, on suspicion of treason, along with the general Konstantinos Strategopoulos. The historian Gregoras implies that these two were the bastion of Anatolian defenses, making this another example of Palaiologan insecurity undermining the interests of the state.”

DESPERATELY NEEDED VICTORIES

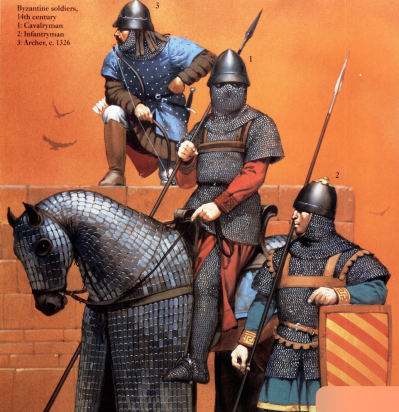

Andronikos removed those men, but luckily found himself someone not only capable of defending Anatolia, but retaking lands there: “Those generals were replaced with Alexios Philanthropenos, a nephew of both the Basileus & Tarchaneiotes, the leader of the Arsenites. He was given an emergency command to save Anatolia, and that is exactly what he did, with an army that included a strong Cretan contingent. In 1294, he defeated some Turks who were threatening Achyrous in the north and then, in a series of brilliant campaigns, inflicted many defeats on the Turks of Mentese. He retook many forts, cleared the way to Miletos, and in 1295 liberated that city too.” Things were going so well, but then, familiar patterns arose. “The curse of the victorious general struck again. Philanthropenos rebelled against the basileus(emperor), whereupon another general, loyal to the regime, bribed some of his Cretan soldiers to arrest him and blind him. Success had made Philanthropenos ambitious, and circumstances favored rebellion.”

The reason a rebellion favored was simple, Anatolia was falling apart, and the local Romans wanted a return to being looked after as they had been under the Laskarid dynasty of Nicaea. The Palaiologans did not care about them enough, and failed to protect them. “Both the locals and the army preferred a present hero over a distant ruler with an indifferent reputation.” So it may seem like Andronikos was right to remove generals, because Philanthropenos rebelled.

A VICTIM OF HIS OWN SUCCESS

It seems likely that Philanthropenos knew he had been too successful, and because people wanted him to rebel, Andronikos would deal with him either way as he had done to others before him. The culture of punishing success created a cycle of successful general rebelling. “Philanthropenos had reason to fear that his success would incur royal suspicion, so his rebellion was partly preemptive. The final straw was when Andronikos demanded that the general send to him all the plunder from the campaign, beyond the due that normally went to the Basileus. Andronikos was possibly being more than greedy here: he was seeking to undermine his general’s standing with his own soldiers.” Thus, it is hard not to see the rebellion of Philanthropenos as directly caused by Andronikos II.

THE SAVIOR THAT WAS NEEDED

The reality was that the Romans needed a Theodore Laskaris, or an Alexios Komnenos to save them. Instead, the ability of Andronikos Palaiologos to maintain power actively undermined imperial power. Normally, an emperor keeping power offers stability. However, a stability of constant failure is counter-productive. It is hard not to feel bad for the people of Roman Anatolia at this time, they were being highly taxed and yet not properly defended. The Palaiologans distrusted the Romans in Anatolia for political purposes, knowing they did not admire the Palaiologos family. The Catalan company later on showed the same thing: “that the Turks could be beaten.” If only someone like Philanthropenos had removed him from power, and refocused the state more on Anatolia, history may have been very different. Instead, the Emperor actively hindered successful men in a way which doomed his own people.

When victories threaten the Emperor, the Emperor punishes victory. For this reason, in my estimation, Andronikos II is among the worst Emperors in Byzantine history. The Roman Empire did not have the luxury of sabotaging its own success in the midst of an existential crisis.

SOURCES:

The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium by Anthony Kaldellis