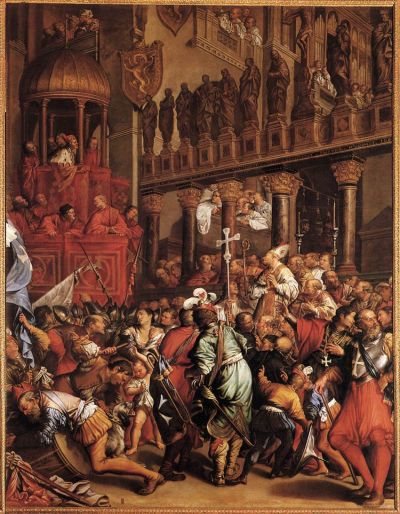

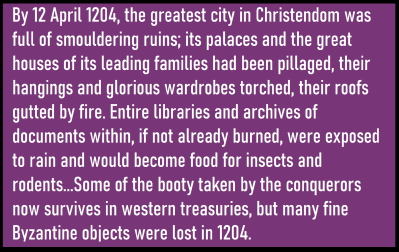

In my estimation the Fourth Crusade was the important event in Byzantine-Roman history. This was the point from which there was no return. It was a moment when an ancient world, the city of Constantinople, came crashing down to a more medieval and less glorious reality. Constantinople had withstood great threats such as the Arab siege of 717, and had been the refuge of the Romans in hard times. However, this time the city was taken due to poor leadership, lack of a navy, and a collapse in the will of the people to resist. The Byzantine world was sent into a decline it could never fully recover from, despite an admirable effort by the Nicaean Emperors. The Fourth Crusade is a topic that comes up over and over in Byzantine history, because so many things came to an end in 1204, and it is a dark story that must not be forgotten. I hear many modern people express sympathies for the victims of the crimes of the Crusaders in the Levant, but they do not even know that the Romans suffered the longest-lasting Crusader states, longer than any in the Middle East. To this day, Greece is dotted with Frankish and Venetian crusader castles. They do not realize how superior Constantinople was to the rest of Europe when it came to culture, architecture, history, population, art, and wealth. The story of how a group of Catholic warriors who claimed to be fighting for God and swore to go to the Holy Land to fight Muslims ended up destroying the largest Christian city in the world must not be forgotten. It is a fascinating tragedy.

STRATEGIC BACKGROUND: THE LEGACY AND DEATH OF MANUEL KOMNENOS

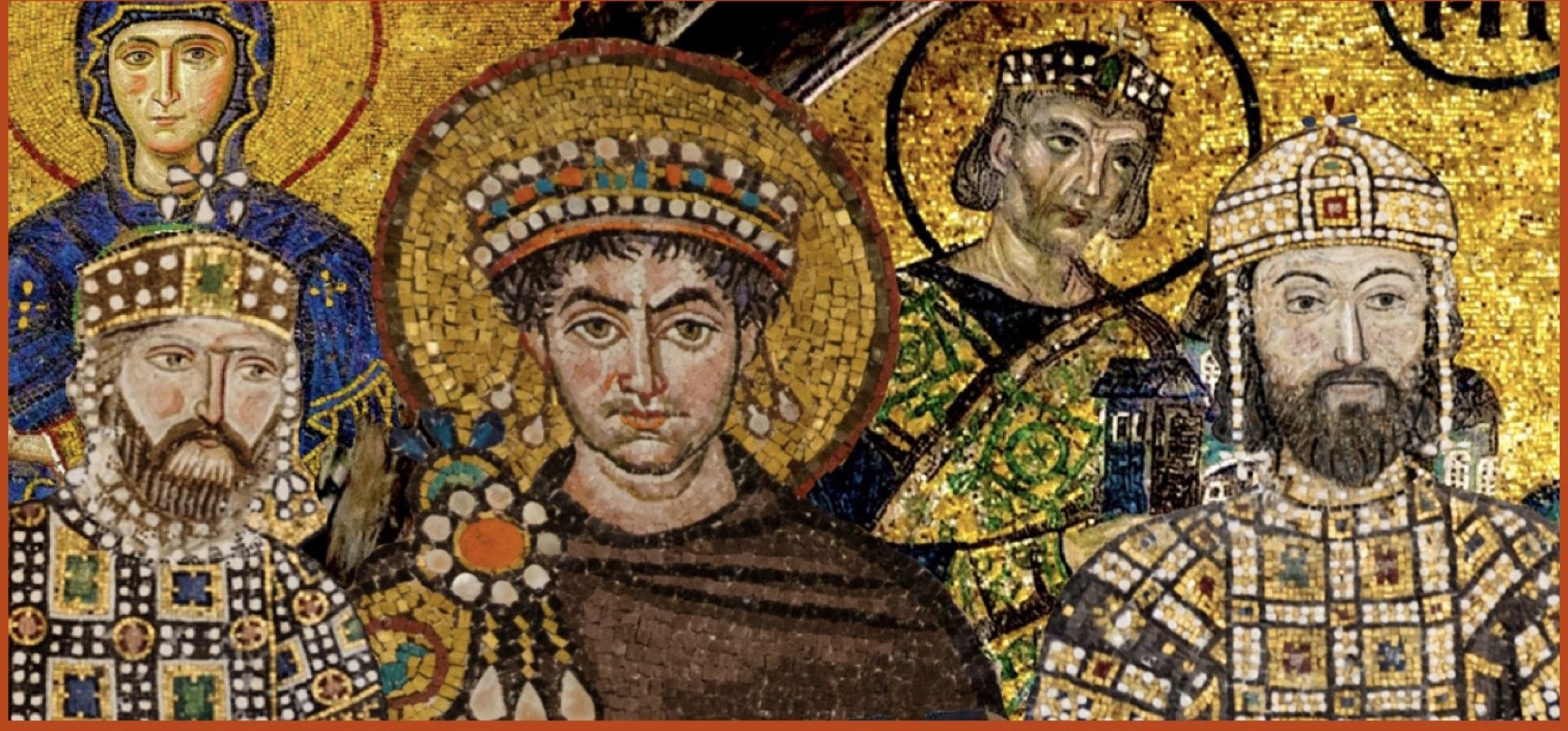

Manuel Komnenos was the last ruler of the Komnenian restoration, which had been started by Alexios Komnenos in 1081, and ended with the death of Manuel in 1180. His rule is controversial in terms of its evaluation. Alexios had used the First Crusade to begin the reversal of Roman fortune after incompetent rulers had lost Anatolia in the 1070’s. On one hand, when Manuel died the Roman Empire was the strongest on paper it had been since the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. On the other, he achieved nothing long-term for the Roman Empire and 24 years after his death Constantinople fell to Crusaders, was irreparably devastated, and the Empire barely survived after that only as a shadow of its former self. How much of that is to blame on him versus the incompetence of his successors is hard to fully decipher.

The Komnenian geopolitical reality was one where Byzantium had many enemies surrounding it, and Manuel was able to hold his own and defeat many of them. He was able to impress Crusader lords, Western monarchs, and prevent civil wars. What he was not able to do, however, was turn his wealth into lasting power and tangible gains for the Roman Empire. Manuel did not really solve any issues for the Roman Empire; he just managed them in his reign. His enemies feared him enough to wait until he died and then they all attacked Byzantium, but he did not use his strength to eliminate any enemies, particularly the weakened Seljuk Turks.

The Romans had a problem with the Italian merchants increasingly exerting influence in imperial waters. The Venetian problem originated in trade concessions made by Alexios Komnenos, who was in a much tougher position than Manuel and needed Venetian assistance against the Normans of Sicily and Southern Italy who had been invading the Balkans. These privileges meant the Venetian merchants paid no tax in the Byzantine Empire on their goods, but it also meant the Republic of Venice was pledged to help protect the maritime interests of the Romans. Mainly it was to offset potential Norman invasions from Italy. However, Manuel soured relations with Venice in his reign. The Venetians were becoming insolent, disregarding imperial power, and not really offering the Romans much in the way of naval assistance. Thus, Manuel had some good reasons for going to war, but did not solve them and left a bitter enemy that would come back to haunt Byzantium. Without the Venetian fleet involved, the 1204 fall of Constantinople was rather unlikely if not outright impossible. Manuel had defeated the Venetians at sea, and yet made peace without truly resolving the underlying issues or pressing the advantage. Tensions continued to rise after his death.

The inability to defeat the Turks is the most clear criticism of Manuel. Manuel spent most of his reign focusing on a host of other issues, including two failed Egyptian expeditions, a failed Italian expedition, impressing Crusader lords, building new palaces, etc. However, the real goal of the state should have been returning Anatolia to Roman rule. It had always been the core of the Byzantine Empire. Manuel finally made a botched full-force attempt at the battle of Myriokephalon (1176) with the strongest Roman army since Manzikert, but led the army in inept fashion. He failed to scout for the predictable Turkish ambush, and he never again had the chance for such a huge expedition. In 1177 the Turks were actually much more heavily defeated by the Romans at Hyelion and Leimocheir, meaning the military balance was still in Byzantine favor. However, as Manuel still could not subjugate the Turks, once he died they came back and began quickly reversing the century of Komnenian efforts to restore the Roman position in Anatolia.

The Norman problem was not resolved by Manuel either. He was able to subjugate the Norman crusader principality of Antioch in the Levant, but not truly conquer it. He also tried to retake southern Italy with an expensive expedition which garnered initial success, but failed miserably at great cost in the end. This soured Byzantine-Norman relations further and they would invade the Empire after his death, culminating in the sack of Thessaloniki in 1185, just five years after Manuel died, a brutal foreshadowing of 1204.

THE ARREST OF THE VENETIANS(1171):

In the reign of Manuel, there was an event which had spawned the war between Byzantium and Venice. Niketas Choniates wrote in his history about the growing influence of the Venetians in Roman society: The Venetians “are vagabonds, like the Phoencians, and cunning of mind. Adopted by the Romans when there had been need for naval forces, they had left their homeland for Constantinople in swarms and by clans. From there they dispersed throughout the Roman Empire; retaining only their family names and looked upon as natives and genuine Romans, they increased and flocked together. They amassed great wealth and became so arrogant and impudent that not only did they behave belligerently to the Romans but they also ignored imperial threats and commands.” Over time, this belligerence became treasonous and intolerable to the Emperor Manuel Komnenos.

Eventually, “buffeted by a series of villainies, one worse than the other, the Emperor now recalled their offensive behavior on Kerkrya and turned the scales against them, spewing forth his anger like the tempestuous and stormy spray blown up by a northeaster or northwind. The misdeeds of the Venetians were deemed to be excessive, and letters were dispatched to every Roman province ordering their arrest, together with the confiscation of their communal properties, and designing the day this was to take place [12 March 1171]. On the appointed day, they were all apprehended, and a portion of their possessions was deposited in the imperial treasury, while the greater part was appropriated by the governors.” The Venetian reaction was war, and although a peace would be made, reoperations paid by Manuel, the Venetians seemingly never let go of the grudge which was formed by these events.

THE MASSACRE OF THE LATINS:

Another event in Roman history, certainly in the context of this story the least defendable actions taken by the Romans, is the massacre of the Latins. After Manuel had died in 1180, his child Alexios II Komnenos was never able to to rule as intended. Instead, Andronikos came in and had the boy sign his own mother’s execution order, then later had him strangled. Andronikos Komnenos also soured relations with the West more than any other.

In April of 1182, when Andronikos was entering Constantinople for his coup against the regent Empress Maria of Antioch(wife of Manuel and mother of the young Alexios II) – he sent his Anatolian soldiers ahead of him to incite a fury against the Latins in the city. Donald M. Nicol wrote in Byzantium and Venice that “the people needed no encouragement. With an enthusiasm fired by years of resentment they set about the massace of all the foreigners that they could find. They directed their fury mainly agains the merchants quarters along the Golden Horn. many had sensed what was coming with the arrival of Andronikos Komnenos and made their escape by sea. Of those who remained, the Pisans and Genoese were the main victims. The slaughter was appalling. The Byzantine clergy shamelessly encouraged the mob to seek out Latin monks and priests. The pope’s legate to Constantinople, the Cardinal John, was decapitated and his severed head was dragged through the streets tied to the tail of a dog. At the end some 4000 westerners who had survived the massacre were rounded up and sold as slaves to the Turks. Those who had escaped by ship took their revenge by burning and looting the Byzantine monasteries on the coasts and islands of the Aegean Sea.” Chilling scenes, and though the Romans would pay reparations for this event, they would still suffer a revenge even greater than the offence.

THE DECLINE OF THE BYZANTINE NAVY:

Why was such a seemingly invincible city able to fall? The navy was the deciding factor in the fall of Constantinople to the Latins, the quote above by Jonathan Phillips is exactly right. The Romans had always, even in dark times, maintained a strong fleet. The Arab siege of 717 was won by the Byzantines because the imperial fleet destroyed the Arab fleet with Greek fire. The naval power of Byzantium was maintained during the Komnenian period despite some reliance on the Venetians. The Venetians did control the Adriatic, but in the Aegean the Romans still reigned supreme and could defeat anyone.

During the reign of Manuel, the Venetians sent a massive fleet in 1171 to seek revenge for the imprisonment of Latins in the capital and revocation of Venetian trade privileges, but Manuel’s fleet was able to stop them. The Roman fleet still had 150 ships in the engagement, a very large force. Manuel was able to dispatch fleets to southern Italy, the Levant, and Egypt. This showed just how far Roman naval power was able to be projected. William of Tyre, a Latin crusader historian wrote that Manuel sent: “150 ships of war equipped with beaks and double tiers of oars…there were in addition, sixty larger boats, well-armoured, which were built to carry horses…also ten or twenty vessels of a huge size…carrying arms and…engines and machines of war.” However after 1180, when Manuel died, the Roman fleet was simply not replaced. Wooden ships do not last a long time, and must constantly be replaced. Even in 5-10 years a fleet can just disappear without investment. By 1203, Choniates says that Alexios III “…began to repair the rotting and worm-eaten small skiffs, barely twenty in number…” Contrast that to William of Tyre, and compare it to the Venetian fleet, and disaster was inevitable. Greek fire seems to have been lost by then as well.

ORIGINS OF THE FOURTH CRUSADE

The Crusader States which had been founded in the Levant following the success of the First Crusade were defeated decisively at the Battle of Hattin in 1187 by Saladin. The Pope Gregory VIII wrote the following after the fall of Jerusalem:

“On hearing with what severe and terrible judgment the land of Jerusalem has been smitten by the divine hand…Saladin’s army came on those regions…our side was overpowered, the Lord’s Cross was taken, the king was captured and almost everyone else was killed by the sword or seized by hostile hands…The bishops, and the Templars and Hospitallers were beheaded in Saladin’s sight…those savage barbarians thirsted after Christian blood and used all their force to profane the holy places and banish the worship of God from the land. What a great cause of mourning this ought to be for us and the whole Christian people.”

The Crusader states in the Levant were being defeated, Jerusalem had fallen, and by the time of the Fourth Crusade only consisted of Antioch, Tripoli, and Tyre. The Third Crusade did very little to change the situation, despite the fame of King Richard the Lionheart.

The Fourth Crusade was called by Pope Innocent III in 1198 and took a few years to materialize. The papacy itself genuinely intended this to be a mission to the Holy Land to fight the Muslims, and finally reverse the losses. Except this crusade would never make it there…instead, as Pope Gregory said of Saladin, the group of men gathered for the Fourth Crusade would also thirst for Christian blood. They would use all of their force to profane the holy places of Constantinople, the largest and most advanced Christian city in the world.

THE VENETIAN DEAL

The Fourth Crusade seemed a bit harder to organize than the first few crusades had been and had a logistical problem in terms of how to get to the Holy Land. The Crusade leaders had decided that it was best to travel there by sea. The Second Crusade had been dealt bitter defeats by the Turks in Anatolia, as well as come to blows with the Byzantines in a battle between the Germans and Romans outside Constantinople in 1147. The Third Crusade had found safe passage by sea, and therefore the Fourth Crusade chose this route as well. It was also determined that an attack on Egypt would help secure Jerusalem, and a fleet would assist in the endeavor. However, as the Crusaders had no fleet, they had to purchase one from a maritime power. The natural choice was the Republic of Venice, but they had no intentions of offering any pious discounts for their fellow Catholics on their “holy” mission.

The leaders of the Crusade assembled at Compiegne, and chose six representatives to send to Venice to secure a deal to transport the army to the Holy Land. At this point no one was talking about attacking Constantinople, this was still a genuine attempt to reinforce the Crusader States in the Levant. These agents were given official charters, which were sealed documents offering guarantees to Venice that any deal would be honored. This deal was where the Crusade began, in hindsight, to take a sinister turn in comparison to previous crusades.

Venice was to be at the heart of the new direction of the Crusade, as it wielded immense power over the army that relied on it to transport it. The Venetians were a merchant republic, they knew how to negotiate a deal better than anyone. One can look to the extortionist trade deals made with Alexios Komnenos to aid against the Normans to see that. When the envoys arrived, the leader of Venice, the Doge Dandolo welcome them. He was around 90 years old by this time, and blind. There actually is a legend that Dandolo was blinded by Manuel Komnenos, but this is not supported by the sources, and is extremely unlikely. It sounds to me like a legend which was used to add a layer of revenge and moral justification to this story. Literary devices are common in ancient and medieval histories.

Jonathan Phillips included in his book that one of the envoys said to the Venetians: “My lords, we have come to you on behalf of the great nobles of France, who have taken the cross to avenge the outage suffered by our lord, and if God so wills, to recapture Jerusalem. And since our lord knows that there is no people who can help them so well as yours, they entreat you, in God’s name, to take pity on the land overseas, and the outrage suffered by our Lord, and graciously do your best to supply us with a fleet of warships and transports.” The Venetians were of course keen to look pious, but responded as the calculated shrewd merchants they were.

Dandolo responded: “How can this be done?”

The Crusader envoys were open minded and said “In any way that you care to advise or propose, so long as our lords can meet your conditions and bear the cost.”

With that, the Venetians got to brainstorming, and took a full week to calculate the best way to profit from the situation. This was quite possibly the biggest contract in Venetian history. Jonathan Phillips described the scale: “To transport the French crusaders to the Holy Land necessitated a level of commitment unprecedented in medieval commerce. The number of ships required would absorb almost the entire Venetian fleet and would entail the construction of many new ships as well. To devote the manpower of the city to one project was a breathtaking idea; in fact, it would require the suspension of practically all other commercial activity…” The Venetians did go all in on this, finding a way to seem to support the cause of the Crusade, and to profit as well. But, now they needed the Crusaders to pay up or the Venetian state itself was in trouble.

Thus the Venetians made serious demands, with Dandolo’s offer to a supply a fleet recorded by Geoffrey of Villehardouin:

“We will build transports to carry 4500 horses and 9,000 squires, and other ships to accommodate 4,500 knights and 20,000 foot sargeants. We will also include in our contract a nine month supply of rations for all men and fodder for all the horses. This is what we will do for you, and no less, on condition you pay us four marks per horse and two per man. We will, moreover abide by the terms of the covenant we now play before you for the space of one year from the day on which we set sail from Venice, to act in the service of God and of Christendom, whichever it may be. The total cost of all that we have outlined here amounts to 85,000 marks. And we will do more than this. We will provide, for the love of God, fifty additional war galleys, on condition that so long as our association lasts we shall have one half, and you the other half, of everything we win, either by land or sea. It now remains for you to consider, if you, on your part, can accept and fulfil our conditions.”

The Crusaders accepted the offer, and now the Crusaders had something they never had, a powerful cutting edge fleet to accompany a powerful army. This is what made this army a threat to Constantinople, the potent combination. The First Crusade had a powerful army, even more powerful than the Fourth Crusade, but with no fleet it would have struggled to besiege the Roman capital. However now this was the biggest threat Constantinople had ever seen, were this army to be at its doors. At this point in the story the Crusaders still did not intend to go there, but that is where they will end up.

THE CRUSADERS FAIL TO PAY:

The problem with the deal was the made it an assumption that a certain number of men would arrive in Venice to go on the Crusade. The 85,000 mark price counted on a certain number of men and horses showing up for the campaign as stipulated by Dandolo. The crusaders ordered a fleet to transport 33,500 men. To put it in context, the price for this fleet was twice the annual income of the King of France. It shows the extreme commitment both sides had to this deal. But the crusaders overestimated their numbers, and thus although they could pay the rate per man and horse, they did not have enough numbers to pay the total sum for the fleet they had ordered. Venice spent 13 months building ships, bought extreme quantities of food for 33,500 men, and ceased other commercial activity to focus on this deal, such a vast amount money could not simply be discounted.

By the fall of 1202, the Venetians could see quite clearly that the numbers of crusaders who had arrived at Venice were not enough to pay the agreed sum. 12,000 men had arrived, compared to the 33,500 expected soldiers. Dandolo was infuriated and issued a warning to the crusaders:

“Lords, you have used us for ill, for as soon as your messengers made the bargain with me I commanded through all my land that no trader should go trading, but that all should help prepare this navy. So they have waited ever since and have not made any [money] for a year and half past. Instead, they have lost a great deal, and therefore, we wish, my men and I, that you should pay us the money you owe us. And if you do not do so, then know that you shall not depart this island before we are paid, nor shall you find anyone to bring you anything to eat or drink.”

12,000 soldiers now were waiting in Venice, short a vast sum, with Venice becoming an increasingly hostile host. The poorer crusaders suffered most during this waiting period, feeling as if they were the victims of their leaders poor planning. The Venetians price-gouged them for food, and controlled them strictly. Some crusaders even deserted due to this hardship and lack of direction, and for those who stayed a disease broke out in the camps. Villehardouin blames this hardship on the failure of those who swore oaths to crusade to show up in Venice, saying it was “the fault of those who have gone to the other ports.” The reality is, there was no promise by all the crusaders to go to Venice, and expensive deal agreed probably made some choose other routes to avoid the cost. It seemed like the crusade would fail. The crusade leaders tried to raise as much as they could to pay the Venetians, they were still short despite offering every available resource.

FORGET THE HOLY LAND:

The Venetians, having invested so much, could not simply write this investment off. Dandolo had used his reputation to convince the Republic to back his plan, and it was failing. The infamous Doge can be criticized for his greed, but not his cleverness. He came up with a revolutionary but sinister and controversial alternative. The Venetians decided to extract their payments from other Christians. For the first time, a Crusader army was directed at Christian cities. Venice identified the city of Zara, on the Dalmatian coast, as a key target. The city was under the rule of King Emico of Hungary, a fellow Christian who actually had also backed the crusade. This means that the Crusade now had gone against the orders of the Pope, who ordered states who went on Crusade to be spared from attack while on their holy mission. This was an offense that could result in excommunication by the Pope for violating his guarantee of safety for the homelands of those who participated in the Crusade. Venice now had taken full control of this crusade from those who launched it and from the Papacy, and it now was never going to be facing any Muslim armies. At this point, the only thing making this a crusade was the rhetoric of its leaders, never again would this group actually act like it was truly on a crusade.

The Crusade leaders agreed to attack Zara, but hid it from their soldiers. This story is full of manipulation, greed, and lies on both sides. The powerful men in charge just told their ordinary men that their payment would be taken out of the spoils of war until the Venetians were repaid. The crusade, based on lies, now set forth to the Balkans. Zara had been a wealthy independent merchant city, associated at this time with Hungary, but at one time under the domination of Venice. In 1181 they had broken free of Venetian rule, and now was the time to force them back into subjugation. It was wealthy and well-fortified, but the Venetian fleet had been built to attack cities in Egypt, and the city was taken. On the way to Zara the Venetians used this crusader army to force other Christian cities like Trieste and Muglia into accepting the authority of Venice. Venice was using this army to propel itself into a major power, Dandolo had turned a loss into a win for the Republic. These attacks were also like practice runs for the coming siege of Constantinople, demonstrating the effectiveness of the Venetian fleet against fortified cities.

THE ROLE OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH:

It is important to clarify that Pope did not certify these attacks on Christian cities, and never would certify the attack on Constantinople. Pope Innocent III had his representative Cardinal Capuano try to convince the crusaders to go to Alexandria instead of Zara, but he failed and Capuano seemed to understand Ventian sentiment. The Pope wrote a letter, the exact words not surviving, which condemned attack on Zara and threatened excommunication from the Church for the participants. But, his own legate, Capuano undermined his authority. So although the Pope Innocent III did not sanction this, the Catholic Church cannot entirely be absolved of guilt as an institution. It is also important to note that Papacy was guilty as an institution for supporting certain endeavors in the past. For example, Bohemond the Norman prince led an invasion of Byzantium with papal support after the First Crusade before being defeated by Alexios Komnenos. Other attacks by Crusaders on Christians were never condemned and de facto legitimized by the lack of negative reception in the West. Richard the Lionheart had conquered Cyprus, permanently severing it from the Byzantine world. The Principality of Antioch, a Norman Crusader state, had attacked Byzantine Cilicia and brutally raided Cyprus. However Zara was unique because it was a Catholic city. But now that Pandora’s box was open, the Crusade was not following any rules and had been hijacked by Venice.

I want to highlight that not everyone in the Fourth Crusade was ok with this change in direction to attack Christians. Simon of Montfort and a group of other French nobles, noting Papal disapproval, expressly disagreed with the attack on Zara. Simon even told Zaran diplomats that the French had no problem with them and they should not surrender to the Venetians. While his other French colleagues supported the attack as a means to pay their debts, I think it is important to remember that not everyone in the crusade was insincere in their intent to go to the Holy Land. Simon and others ultimately left the crusade, which left the remaining group of men with that much less of a conscious. Those crusaders left were those who had no issue with attacking Christians, and would eagerly seize any opportunities to make money.

After Zara had surrendered and the spoils of the city taken, the crusaders had to wait for the Papal reaction. Innocent III seemed to blame Venice said that the crusaders had “fallen in with thieves.” The Pope declared that the army no longer could earn remission of sins in this missiona as previous Crusades claimed. The Pope protested the Venetian looting of Zaran churches, but clearly the Venetians did not care as they would take that to new heights in 1204. It is clear that Venice was the mastermind of the Fourth Crusade now, and was employing it to build an Empire. Even the Pope knew this. This crusade would make Venice far more powerful than it ever had been, and the Pope had no control over its direction.

INVITING DISASTER:

In December of 1202, after seizing Zara, the Crusader army encamped there. That was when ambassadors arrived representing Alexios IV Angelos, the young son (around 20 years old at this time) of the ex-Emperor Isaakios Angelos. The message read:

“Since you are on the march in the service of God, and for right and justice, it is your duty to restore their possessions to those wrongly dispossessed. The Prince Alexios will make the best terms with you ever offered to any people and give you the most powerful support in conquering the land overseas…Firstly, if God permits you to restore his inheritance to him, he will place his whole Empire under the authority of Rome, from which it has long been estranged. Secondly, since he is aware you have spent all your money and now have nothing, he will give you 200,000 silver marks, and provisions for every man in your army, officers and men alike. Moreover, he himself will go in your company to Egypt with 10,000 men, or if you prefer it, send the same number of men with you, and furthermore as long as he lives, he will maintain, at his own expense, 500 knights to keep guard in the land overseas.“

This is when Constantinople fell into the crosshairs of this crusading army which had fallen in with thieves. Alexios Angelos gave them an offer they could not resist, so grand that the Romans never could have actually honored it. This whole crusade seems to have taken a turn from the grandiose promises of a young man who did not know anything about governing, the Byzantine economy or situation. The childish Alexios IV Angelos had linked the idea of restoring him to the throne with a more successful crusade, giving the crusaders a self-justification for their future actions. The Crusaders, likely unhappy at being at odds with the Pope, seemed to have thought that forcing Byzantium back into the jurisdiction of Rome would restore their standing. Guntheir of Pairis wrote that: “It helped to know that this very city [Constantinople] was rebellious and offensive to the Holy Roman Church, and they did not think its conquest by our people would displease very much either the supreme pontiff or even God.” While Pope Innocent had not sanctioned this move, clearly the average rank and file crusaders thought he would approve of it nonetheless. This is not the first time this argument was used either, during the Second Crusade the French had similar sentiments. Odo of Deuil recorded in On Louis VII’s journey to the East that killing Byzantine people was no moral problem, and that “they were judged not to be Christians, and the Franks considered killing them a matter of no importance.” The Byzantines had been slandered and portrayed as traitors and heretics ever since the siege of Antioch in the First Crusade. This sentiment had now become truly deadly.

The crusaders were excited at this offer. Their debts could be lifted, and in fact they could go from indebted to enriched from this deal, and have a Byzantine army of 10,000 men to join them in Egypt. Add 500 knights to defend any new territory taken by the Fourth Crusade, and it was truly an unprecedented offer. The Venetian and French leaders convened, and debated the matter. The Abbot Guy of Vaux-Cernay opposed this idea because “it would mean marching against Christians. They had not left their homes to do any such thing, and for their part wished to go to Syria [the Holy Land].” But, sadly, most were in favor of the crusade going to Constantinople, arguing it was restoring the rightful ruler to the throne,aiding the crusade, and forcing the heretical Byzantines to accept the supremacy of Rome all at once. Robert De Clari records Dandolo encouraging the attack, arguing that the Byzantines were wealthy, and arguing that if “we could have a reasonable excuse for going there and taking the provisions and other things…then we should well be able to to go overseas.” The Venetians, a notable player in the Byzantine economy, knew just how many riches were on offer at Constantinople. Gunther of Pairis also says the Venetians were greedy and wanted the money, and also because “their city, supported by a large navy, was, in fact, arrogating itself to be sovereign over that entire sea.” In other words, the Venetians were masterminding geopolitical concerns rather than thinking of Jerusalem, even according to Western historians.

Robert De Clari also recorded another dialogue with the Doge Dandolo of Venice, regarding the suggestion to venture to Constantinople:

“‘Lords,” said the Doge, ‘now we have a good excuse for going to Constantinople, if you approve of it, for we have the rightful heir.’ Now there were some who did not at all approve of going to Constantinople. Instead they said: ‘Bah! What shall we be doing in Constantinople? We have our pilgrimage to make, and also our plan of going to Babylon or Alexandria.'” But, despite deliberation, the Crusade now had its eyes set on the fortunes of the Queen of Cities. The Crusade ultimately followed the money, and Alexios IV Angelos had convinced an army to go to Constantinople which would inflict a mortal wound on Byzantine civilization from which it would never recover.

THE ARMY SETS SAIL TO CONSTANTINOPLE:

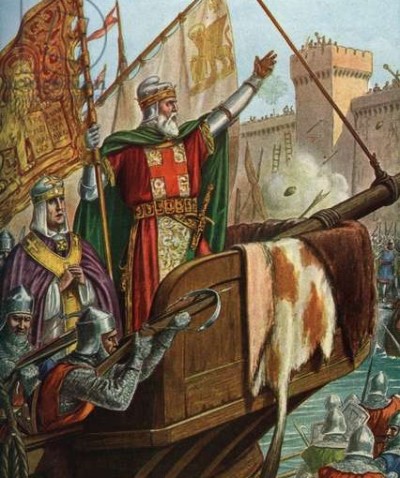

Alexios IV Angelos joined the crusaders at Zara on April 25, 1203. The army sailed to Constantinople in their massive Venetian armada, stopping first at the Greek island of Corfu. The Crusaders seemed to see justification for the cause when the strategic city of Dyrrachium opened it’s gates to Alexios Angelos as the fleet passed by. But, it is highly likely that the residents heard what happened at Zara and simply preserved their city by doing so rather than them actually being big supporters of Alexios IV. It made the Crusaders perceive that the people of the Roman Empire wanted the restoration of their “rightful” ruler perhaps, and maybe they even imagined Constantinople opening itself to them as well. Because some crusaders like Simon had abandoned the crusade after it attacked Christians, there were worries the army was too small. However, after an argument between Orthodox and Catholic clergy on Corfu regarding the supremacy of Rome and the Pope, Alexios had the Crusaders raid the island to send a message to the Byzantine people that he would stop at nothing to be Emperor. On May 24, 1203, the army left Corfu and set sail to Constantinople.

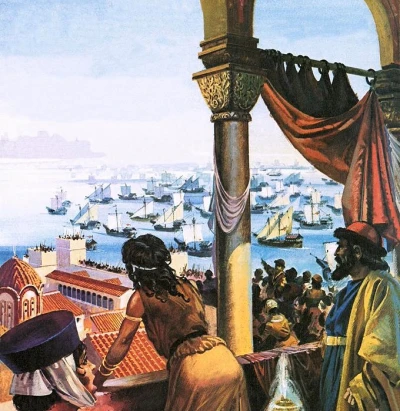

It is clear that the mission was less and less being centered on eventually going to the Holy Land, and increasingly on material gain. Along the way, the men of the Fourth Crusade encountered a separate group of crusaders returning from the Holy Land, and some of them joined them. For piety? No, but instead one wrote that they were going “with these people, for it certainly seems to me they’ll win some land for themselves.” This mission clearly had appeal to those seeking wealth and new lands to conquer. Which makes one wonder what they actually thought would happen when they got to Constantinople. The Crusade was able to sail unopposed into the Sea of Marmara, unthinkable during the reign of rulers like Alexios, John, or Manuel Komnenos. However, the ease of travel to Constantinople did not mean they would be well received in the Eastern Roman capital.

IMPERIAL PREPARATIONS:

The city was naturally defendable, but its ruler, Alexios III Angelos was incompetent and failed to properly organize the defense. The Emperor had been aware that his nephew was plotting with the crusaders to eliminate him, and did not use all the time at his disposal to prepare. Choniates is scathing in his description of Alexios III’s neglect of the situation:

“…his excessive slothfulness was equal to his stupidity in neglecting what was necessary for the common welfare. When it was proposed that he make provisions for an abundance of weapons, undertake the preparation of suitable war engines, and above all to begin the construction of warships, it was as though his advisers were talking to a corpse. He indulged in after-dinner repartee and in willful neglect of the the reports on the Latins [the Crusaders]; he busied himself with building lavish bathhouses, levelling hills to plant vineyards…wasting his time in these and other activities. Those who wanted to cut timber for ships were threatened with the gravest danger by the eunuchs who guarded the thickly wooded imperial mountains, that were reserved for the imperial hunts, as if they were sacred groves…”

Life went on as usual in the palace for Alexios III, but a harsh reality was moving towards them. The city was not prepared for what was coming. Constantinople, if properly prepared, was nearly impregnable. However the city was not prepared by the incompetent Alexios III, and crucially the Roman navy was in poor condition. This meant that the Crusaders could simply ignore the Theodosian walls and put pressure on the weakest parts of the city.

The decline of Byzantine naval forces under the Angelos dynasty was going to be the determining weakness of the city. Choniates says the Romans only had 20 ships in poor condition wasting away in the harbor, which were repaired but this was not going to compete with the purpose-built top-of-the-line Venetian fleet the Crusaders had ordered. It seems there was no Greek fire in this siege either, that perhaps the secret had been lost, or there was no longer the ingredients available which were needed.

To be fair to Alexios III, Choniates is writing in hindsight, but it is clear he failed to do even an average job in a situation that required effective and proactive leadership. Once Alexios III heard that Alexios IV was proclaimed Emperor by some locals in Byzantine territory, he then began to prepare the city, pulling down some suburban houses around the walls in order to aid the defenders and remove cover for the attackers. But it was too little too late.

THE LATIN FLEET ARRIVES BEFORE CONSTANTINOPLE (1203):

On June 23 of 1203, the Venetian fleet and its crusader army was within sight of the greatest city they had ever seen. The population of the city was possibly as high as 400,000 which was simply unheard of in Western Europe. The very largest European cities besides Constantinople had around 60,000 people at this time. Villehardouin described the impression of the crusaders as they saw the city of Constantine:

“I can assure you those who had never seen Constantinople before gazed very intently upon the city, having never imagined there could be such a fine place in all the world. They noted the high walls and lofty towers encircling it, and its rich palaces and tall churches, of which there were so many no one would have believed it to be true if he had not seen it with his own eyes, and viewed the length and breadth of the city which reigns supreme over all others. There was indeed no man so brave and daring that his flesh did not shutter at the sight.”

They saw massive domed churches like Hagia Sophia, Pantokrator, and Hagia Eirene, still visible from the sea today. The long-gone Church of the Holy Apostles was an impressive site at the time as well. They saw the sea walls as a curtain around the city, the Boukoleon palace, massive columns like those of Constantine and most prominently the column of Justinian which the crusaders described in detail. The Hippodrome must have awed them – large arenas and the Roman Circus was a sight not seen in the west since long ago. But the Hippodrome of Constantinople was still well-maintained at this time, a large impressive structure from Antiquity. Clearly the crusaders knew the work and sacrifice it would take to seize this prize. The Theodosian land walls were so formidable the Crusaders seemed to know that breaking through them was unlikely. Taking note of the grandeur of the city, they took their time, gaining confidence as they approached.

Robert De Clari claims that the Crusaders sent a ship with Alexios IV onboard to convince the people of Constantinople to hail him as Emperor. Supposedly Dandalo spoke to the leaders of the Crusade and “said to them: ‘Lords, I propose that we take ten galleys and place the youth[Alexios IV] on one of them and people with him, and they they go under flag of truce to the shore of Constantinople and ask those of the city if they would be willing to recognize the youth as their lord.’ And the high men answered that this would be a good thing to do. So they got ready these ten galleys and the youth[Alexios IV] and many armed men with him. And they rowed close to the walls of the city and rowed up and down, and they showed the youth, who name was Alexius, to the people, ad they asked them if they recognized him as their lord. And they of the city recognized plainly and said that they did recognize him as their lord and did not know who he was. And those were in the galleys with the youth[Alexios IV] said that he was the son of Isaac [Isaakios Angelos], the former Emperor, and those within answered that they did not know anything about him. Then they came back again to the host and made known how the people had answered them. Then it was commanded throughout all the host that all should arm themselves, both great and small.”

This was when the lies of Alexios IV were first laid bare. His offers of endless treasure, that all they had to do was show up, show him to the people who yearned for his rule, and just free the city, were shown not to be true. The fraud of Alexios IV was beginning to tell, but, the Crusaders, wanting their money, prepared for war. Even if it was gonna be harder than they thought, they needed Alexios IV to get them their cash.

THE BALANCE OF POWER AT THE START OF WAR FOR CONSTANTINOPLE:

In 1203 a fight was shaping up between the two sides. The Crusaders held a clear advantage at sea, with complete naval dominance. Having broken the Golden Horn chain, they could now attack the weakest sections of Constantinople. They could ignore the Theodosian walls, and focus on the Blachernae walls by land, and the weak Golden Horn sea walls at sea. On land, the Roman forces were of a mixed quality, and included many foreigners. The Varangian Guard were by far the best forces available for the defense of the city, around 5,000 of the famous warriors. These were elite heavy troops, many armed with single-edged axes and well-armored. The Varangians had the capability to properly fight against the elite heavy knights the French would deploy in the battle. There were also some Italians fighting with the Romans from Pisa and Genova, in part motivated by their hatred of Venice and their rivalry. The Romans also had the people of the City, which when determined could be a force of their own. The will of the people to resist would play a big role in the siege at times.

THE CRUSADERS LAND OUTSIDE THE CITY:

Robert De Clari says that after offering Alexius to the people of the City, and the offer having been rejected, the Crusaders formed a plan to attack. He says they confessed their sins, received communion from priests, and prayed in order to prepare themselves spiritually. Robert explicitly stated that this was out of fear of attacking the city on the part of the Latin soldiers. Which, is understandable given the task and the looming fortress-metropolis that Constantinople was. The first step was landing, and taking the the Galata suburb.

Despite their fears, the Crusaders did set to task. Choniates says the Crusaders took three days “to lay down strategy,” which is probably the same period of preparation described by Robert De Clari. The Crusader historian says “when the people of the city saw this great navy and this great fleet and heard the sound of the trumpets and the drums, which were making a great din, they all armed themselves and mounted on the houses and on the towers of the city. And it seemed to them that very much as if the whole sea and land trembled and as if all the sea were covered with ships. In the meantime, the Emperor had made his people come all armed to the shore to defend it. When the crusaders and the Venetians saw that the Greeks were to come to the shore all armed to meet them, they talked together until the doge of Venice said he would go in advance with all his forces and seize with shore with the help of God. Then he took his ships and his galleys and his transports and put himself in front at the head of the host. Then they took their crossbowmen and their archers and put them in front on barges to clear the shore of the Greeks, and when they were drawn up in this way, they advanced to the shore. When the Greeks saw that the pilgrims were not going to give up coming on to the shore for fear of them, and saw them approaching, they fell back and did dare wait for them. And so the fleet made the shore.” So it was that the crusaders so easily achieved what should have been a challenging objective, to land safely, without a fight.

The Crusaders were probably surprised just how poorly defended the area around the City was. Choniates says that some Roman forces kept watch, and fired some arrows at them, but none of it was effective. Eventually around July 5-6 of 1203, “not many days had elapsed before the Latins, realizing that there was no one to oppose them on land, came ashore. The cavalry moved out a short distance from the sea, and the long ships, dromons, and round warships moved inside the bay. Both the land and sea forces mounted a joint attack against the fortress, to which the Romans customarily fastened the heavy iron chain whenever an attack by enemy ships threatened, and forthwith they assailed the fortification. It was a sight to behold, the defenders fleeing after a brief resistance. Some were slain or taken alive, and others slid down the chain like it was a rope and boarded the Roman triremes, while many others lost their grip and fell headlong into the deep. Afterwards, the chain was broken, and the entire [crusader] fleet streamed through.” Robert De Clari says the same thing, that the Crusaders landed, took Galata, got the fleet in the harbor and the siege proper could then begin.

Villehardouin wrote in his history that: “Count Baldwin of Flanders and Hainult, with the advanced guard, rode forward, and the other divisions of the host after him, each in due order of march; and they came to where the Emperor Alexius[III] had been encamped. But he turned back towards Constantinople, and left his tents and pavilions standing. And there our people had much spoil.” He also explained just how important the capture of Galata was – “Our barons were minded to encamp by the port before the tower of Galata, where the chain was fixed that closed the port of Constantinople[The Golden Horn]. And be it known to you [the reader], that anyone must perforce pass that chain before he could enter the port. Well did our barons perceive that if they did not take the tower, and break the chain, they were but as dead men…” The first main objective had been accomplished.

The capture of Galata was a crucial element in the siege. The fact it fell in the first attack, without a true battle, immediately set the Romans up without one of their key defense layers. In 1453 for example, because of Genoese neutrality, the chain was unable to be broken by the Ottomans. This helped hold them off, until Mehmed used an ancient tactic to move ships overland into the Golden Horn. The Crusaders did not have the same manpower that the Ottomans had, but they were able to break the chain with ease so they did not need it.

THE CRUSADERS MAKE CAMP OUTSIDE THE WALLS:

Villehardouin says that after taking Galata “Then did those of the host take council together to settle what thing that should do, and whether the should attack the city by sea or by land. The Venetians were firmly minded that the scaling ladders ought to be planted on the ships, and all the attack be made from the side on the sea[Golden Horn walls]. The French, on the other hand, said that they did know so well how to help themselves on sea as on land, but that when they had their horses and their arms they could help themselves on land right well.” And thus, as agreed in all accounts, the attacking force was divided as such.

Now that the Crusaders had landed outside the city, taken Galata, and broken the chain – the siege of the City could begin. The tiny Byzantine fleet of small and run-down dromons had been guarding the chain in the harbor, but once it broke they had to return to port, unable to engage the Venetian galleys. Robert De Clari says the Crusaders then “assembled and took counsel together as to how they should attack the city. And finally they agreed among themselves that the French should attack it by land, and the Venetians by sea. So the doge of Venice said that he would have engines and ladders made on his ships by which they could assail the walls. Then the knights and all other pilgrims armed themselves and set out to cross a bridge which was about two leagues away, and there was no other way to cross over to Constantinople less than than four leagues from there except at this bridge. And when they came to the bridge, the Greeks came there to dispute the passage with them as best they could, until finally the pilgrims drove them away by force of arms and crossed over. When they came to the city, the high men encamped and pitched their tents in front of the palace of Blachernae, which belonged to the Emperor.” The events as narrated by Choniates are more or less in agreement with this narrative. Choniates added the perspective of the defenders in Blachernae, who “could see the raised tents and could almost converse with those within…”

The Crusaders were not stupid, they knew exactly were to attack. They did not waste time attacking the Theodosian walls, and focused on land on the weaker Blachernae section, and by sea on the weaker Golden Horn walls. This was the nightmare scenario for the defense of the city. To have a chance to take the city required naval supremacy by the attackers, and a strong land army, and now the Latins had both. Fortress Constantinople, through lack of preparation and leadership, had lost two advantages. One, the chain across the harbor was gone. Two, the Blachernae walls were exposed. Now the Crusaders could attack them both in close proximity. The advantage that the Theodosian walls still offered was that the walls would not be attacked, meaning they defenders didn’t have to man the entire length of the land walls. However, the sections that were attacked did not have the same robustness.

THE FIRST FIGHT FOR THE QUEEN OF CITIES:

Choniates says that after the Crusaders landed “they were separated from us, not by palisades and camp, but by the City’s walls. Emperor Alexios [III] had long before set his heart on flight, and fully determined to do so, he bore no arms whatsoever. Nor was he seen to offer resistance to the enemy without, but instead sat back as a spectator of the events taking place and ascended to the lofty ‘apartments of the Empress of the Germans [a hall built by Manuel’s first wife Bertha-Irene],’ as they are called. His close friends and kinsmen assembled a cavalry force and a small contingent of infantry and sallied forth at intervals to show that the City was not entirely desolate of manpower.” Below you can see where Alexios III sat idly as critical events unfolded.

6. Hall of Alexios 7. Anemas Dungeons 8. Palace bath 9. Palace of Manuel Comnenus

10. Chapel 11. Palace of Empress Bertha (where Alexios III was at this moment) 12. Tower of Isaac Angelus

In the opening stages of the battle, the sides were fighting small battles outside the walls between cavalry forces. At the same time, the crusaders began using catapults against the walls and the palace of Blachernae. The Romans had their own artillery on the walls and fired back as both sides tried to weaken the other. Choniates says that on July 17th, the Crusader attacks on Constantinople intensified. The Venetians brought their ships, now equipped with the equipment needed to board the walls from their masts, up the walls and began to attack in earnest. They covered their ships with hides in order to prevent the Romans from setting them alight.

By land, the Crusaders tried to use a “wall-storming” battering ram at the same time with crossbowmen in support as it advanced. Choniates describes “the horrendous battle that followed,” saying it was “fraught with groanings on all sides. The heavy-armed troops who surround the battering ram broke through the wall and gained access to a passageway within which led down to the sea to a place called the Emperor’s Gangway, although they were bravely repulsed by the Roman allies, the Pisans and the ax-bearing barbarians [Varangians], and the majority [of the enemy] returned wounded. When those in the ships approached the walls, using the light boats, they cast anchors onto the shore from the scaling ladders, raising the ladders, which were suspended from the stern cables, over many sections of the walls. They then engaged the defenders on the towers and easily routed them, since they were fighting above from a higher vantage point and discharging their missiles from above.” The low height of the Golden Horn sea walls made them poorly defended against the Venetian tactics, which to be fair were extremely well executed.

The Venetians were able to seize sections of the sea walls, putting the defense of the City in jeopardy. For the first but not the last time, the Latins set fire to the City. The houses near the walls were set alight, sending its inhabitants fleeing. This was not a small fire, it burned a decent sized chunk of the city. Robert De Clari says of the fire that “there was burned of it a part fully as large as the city of Arras [a city in France].” Villehardoin said in his account that “when the Emperor Alexius saw that our people had thus entered the city, he sent his people against them in such numbers that our people saw they would be unable to endure the onset. So they set fire to the buildings between them and the Greeks; and the wind blew from our side, and the fire began to wax so great that the Greeks could not see our people…” In the face of such an onslaught, the seaward defenses failing, and the city being burned, Alexios III finally had to do something.

THE MISSED OPPORTUNITY:

Although the Crusaders were formidable warriors without a doubt, the Romans did have one opportunity to attack their forces on land. After such a long period of inaction and lack of leadership, Alexios III realized that if he did nothing he was going to certainly be overthrown. Choniates wrote “when Alexios saw the pitiable plight of the queen of cities and the affliction of the people, he at last he took up arms,” because the people of Constantinople were beginning to see their peril and his obvious lack of leadership or competence. They saw Alexios III as a coward hiding in the palace, not taking any initiative, and naturally were angry and resentful. Niketas records that “the masses were bristling with anger, heaping abuse upon him, and hurling insults against him, for by choosing to remain safe inside the palace and resolving to offer no assistance to the defiled City, he had emboldened the enemy even more.” Probably the Emperor could see the next step in their rage uld be deposing and killing him. Thus, he had to muster the courage to do something. The Romans calculated that if they could defeat the land army, the Venetians, which could not be directly defeated at sea, would likely leave without the manpower to storm the city. It was an apocalyptic scene, fitting for a movie, where the city of Constantinople was burning with blackened skies due to fires set by the Crusaders as Alexios III seemed like he was going to try to save the city.

An opportunity presented itself for the Romans to defeat their doom-bringers. Choniates says “Alexios marched out from the palace, followed by many horsemen and a highborn infantry regiment from among the flower of the City that had hastened to join him, and when the opponents land forces suddenly beheld this huge array, they shuddered. Indeed, a work of deliverance would have been wrought had the Emperor’s troops moved in one body against the enemy, but now the nagging idea of flight and the faintheartedness of those about him thwarted Alexios from what needed to be done. To the joy of the Romans, he drew up the troops in battle array and moved out, ostensibly, to oppose the Latins, but he returned in utter disgrace, having only made the enemy more haughty and insolent.” This was a moment that could have turned the scales. Success of course was not a guarantee, but Robert De Clari’s account from a Latin perspective adds to the sense that Choniates is right that this was a chance for a “work of deliverance” for Constantinople.

The Crusaders, during their attacks on the Blachernae walls, found themselves vulnerable to the Roman counterattack Alexios III was seeming to launch at them. In the morning, when the Crusaders and “Venetians were getting ready and ordering their vessels and had drawn as close to the walls as possible for the assault, behold the Emperor of Constantinople, Alexius [III], sallied forth from the city by a gate called the Roman gate with all of his people fully armed and there he arranged his forces…” Robert De Clari makes wild claims about the numbers of the Byzantine force, such as that it was 100,000 men on horse. Which is clearly false, even in the glory days of Justinian 100,000 horsemen were not ever fielded. Whatever the numbers were, the French land forces attacking the walls felt vulnerable and were outnumbered to some degree. Robert said that the “French saw themselves so surrounded by these battles, that they were greatly dismayed.” Robert De Clari adds that when the Emperor retreated, the women of the City jeered at him for his cowardice. Then, he agrees with the sentiment of Choniates that a huge opportunity was missed – “because he (Alexios III) had not fought against so few people as the French were, with so great a force as he had had with him.” The Romans would not get another such chance to end the siege again. The Crusaders seemed surprised, as they saw the Byzantines as weak, that they even tried to attack. With a capable leader like Alexios Komnenos, John Komnenos, or Manuel Komnenos, I believe the Crusaders would have suffered a defeat in this situation. But that is not history, with them in charge this entire scenario had been averted.

Next, the people of Constantinople were infuriated that Alexios III retreated without a fight. Robert De Clari says “there arose a great clamor in the city, for they of the city told the Emperor that he ought to deliver them from the French who were besieging them, and that if he did not fight with them they would seek out the youth [Alexios IV] whom the French had brought and make him Emperor and lord over them. When the Emperor heard this, he gave them his word that he would fight with them on the morrow. But when it came near midnight, the Emperor fled the city…” Not only that, but Alexios III knew the people would not accept his lack of leadership, cowardice, and selfishness. He probably felt like he Latins could not be defeated anyway. Thus, “he entered the palace and made ready his escape.”

ALEXIOS III ABANDONS CONSTANTINOPLE:

After his failures to defend Constantinople, the Crusader attacks, and the anger of the Roman people against their Emperor, Alexios III decided he had to get out of the City immediately. On the night of July 17-18, he went to the Blachernae palace, and had his most trusted family members such as his daughters loot what was left of the Byzantine funds available. They collected “one thousand pounds of gold and other imperial ornaments made of precious gems and translucent pearls.” Then, that night, he left the city with the treasure in hand. It is truly despicable, selfish, and unbelievable that in the midst of such a crisis that the Emperor could do such a thing. But he did, clearly it ran in the Angelos family tradition to help destroy the Roman Empire. Choniates fittingly wrote that “it was as though he had labored hard to make a miserable corpse of the City, to bring her to utter ruin in defiance of her destiny, and he hastened along her destruction.” It is possible, based on what money the Byzantines would later give to the Crusaders, that with the treasure that Alexios III had taken they could have afforded the ransom of Constantinople. Or, they could have paid more men to defend it. Somehow, it may have made a big difference in the fate of the Roman Empire. However, it was not to be.

Alexios III, the man who had failed to prepare the City for the siege, now left the city to it’s fate. The Angelos family is at the heart of the Byzantine failure of the siege. In this case, his leadership offered so little that leaving had probably not actually hurt the Romans. Nonetheless, it was cowardly. Choniates says “Alexios travelled down the road he had chosen; the people in the palace of Blachernai saw Alexios’ escape as exceedingly insufferable and were thrown into a state of confusion and consternation because of the impending disaster…” However, since Alexios never really offered much in the way of order and organization, it mattered little. “This miserable wretch among men was neither softened by the affection of children nor constrained by his wife’s love, nor was he moved by such great city, nor did he, because of his love for his life and his cowardice, give thought to anything else but his own salvation…” And then the next of the Angelos Emperors stepped back into the fold.

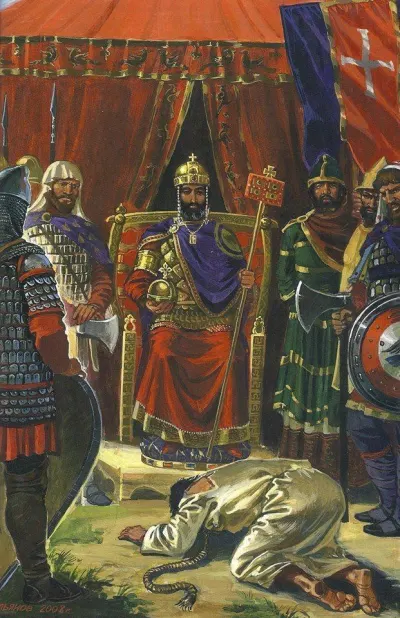

ISAAKIOS RETURNS TO THE THRONE:

Choniates and Robert De Clari tell this part of the story differently. Choniates, who was in the city, is the more likely to understand the Byzantine reaction to events after Alexios III abandoned his subjects. He says that “the eunuch Constantine [Philoxenites], the minister of the imperial treasuries, had assembled the ax-bearers [Varangians] and discussed with them what needed to be done and was assured of the support of a faction that agreed Isaakios should quickly assume the reins of empire. He had the Empress Euphrosyne seized, her relations were taken prisoner, and Isaakios proclaimed Emperor [17-18 1203].” In a most unusual occurrence in Byzantine history, “he who had been blinded was ordained to oversee all things and was led by the hand to ascend the imperial throne.”

The Romans were in a tough position after Alexios III had fled into Thrace. They knew they had to act and feared that “there was nothing and no one to put off and check the Latins who were encamped nearby from making an imminent assault against the City and penetrating inside the walls.” Surpisingly Isaakios Angelos, who had been imprisoned by his own brother Alexios III, was brought out from the prison to the palace and made Emperor. According to Choniates, Isaakios immediately sent word to the Latins and to his own son Alexios IV in the Crusader camp that he was now Emperor and Alexios III had fled the city. The Crusaders could not argue that Isaakios was illegitimate, because his deposition by Alexios III was the source of the claim of Alexios IV to the throne. But now Isaakios was back on the throne, and the whole argument that the Crusaders were putting the rightful Emperor on the throne was negated.

Robert De Clari offers a flowery version of events. He wrote that “When the morning was come on the morrow, what do they do but go to the gates and open them and issue forth and come to the camp of the French and ask and inquire for Alexius, the son of Isaac. And they were told that they would find him at the tent of the marquis. When they came there, they found him, and his friends did him great honor made great rejoicing over him. And they thanked the barons right heartily and said they who had done this thing had done right well and had done a great deed of baronage. And they said that the Emperor had fled, and that they [the crusaders] should come into the city and into the palace as if it all belonged to them. Then all the high barons of the host assembled, and they took Alexius, the son of Isaac, and they led him to the palace with great joy and much rejoicing. And when they were come to the palace, they had Isaac, his father, brought out of prison, and his wife also. This was the one who had been imprisoned by his brother, the recent Emperor. When Isaac was out of prison, he made great rejoicing over his son and embraced and kissed him, and he gave great thanks to the barons who were there and said that it was by the help of God first and next by theirs that he was out of prison. Then they brought two golden chairs and seated Isaac on one and Alexius his son on the other beside him, and to Isaac was given the imperial seat.”

As to how Alexios IV was put on the throne, Choniates is more vague. He says Isaac had to agree to uphold all of the offers of Alexios IV, “that none of the extravagant pledges to the Latins with glory and gain was to be held back. Doing everything to insure against failure in ascending the paternal throne, Alexios, a witless lad ignorant of affairs of state, neither comprehended any of the issues at stake nor reflected for a moment on the Roman-hating temperament of the Latins. Having purchased his entry to the city by the overturn of the imperial majesty, he was deemed worthy to sit on the throne with his father as co-emperor. The entire citizenry, therefore, ran in a bad to the palace to behold the son with his father and pay homage to both.” Probably, Choniates is correct that Isaakios was freed first, as he had more firsthand knowledge of Byzantine affairs. However, it is possible the Romans decided to accept Alexios IV and freeing Isaakios was the logical step knowing Alexios IV would come to the city. Whether Isaakios was freed before or after the arrival of Alexios IV is not important for the rest of the battle in any case.

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR:

Alexios IV Angelos had finally achieved his remarkable dream of being Emperor of the Romans. Surely he had a rush of joy and excitement at being crowned as co-Emperor with his blinded father. Initially, he may have even thought he could actually fulfill the offers he had made the Crusaders. However, reality would set in soon for the young man, setting his naivety into the spotlight. Alexios IV promised the money, and “surely would keep” his promises, but “wished first to be crowned.” The Crusaders took him at this word, and waited for their big payday. Robert De Clari says the majority of the Crusaders “dare not remain in the city at all, because of the Greeks who were traitors, but instead they went to take quarters across the harbor, over toward the tower of Galata.”

Choniates says “not many days later” after his coronation, sometime between July 19 and August 1 of 1203, the “Latin chiefs presented themselves at the palace together with their distinguished nobility. Benches were set before them, and they all sat in council with the Emperors, hearing themselves acclaimed as benefactors and saviors and receiving every other noble appelatio for having honored the power-loving Alexios [IV] in his childish actions, and moreover, for coming to his and his father’s aid in their time of adversity. In addition, they enjoyed every kindness and courtesy. Amusements and dainties were contrived for them, for Isaakios, taking possession of what little was in the imperial treasury and taking into custody Empress Euphrosyne and her kinsmen, whom he robbed with both hands, lavishly bestowed the monies on the Latins.” All was going well, Alexios IV was on the throne, in harmony with the Latins as he had dreamed off when he first lured the Crusaders to the City.

However, there was a huge problem. Alexios III had stolen most of the treasury, Alexios IV essentially started off as an impoverished Emperor with little control over anything other than the city of Constantinople itself. He gave gifts to the Westerners but “the recipients considered the sum to be but a drop” in a bucket of what they were owed. Robert De Clari says after Alexios IV was crowned, that a lord by the name of Pierre of Bracheux stayed in the palace with him, presumably to keep tabs on him, and the money they were owed.

Of course after the crowning of Alexius, the Crusaders expected the money to brought to them as had been agreed. But, Alexios IV had no idea what the state of Roman finances were even in good times, he had never been Emperor, and in the times he had sowed upon the city it was just impossible. Robert De Clari tells us that the “barons demanded their payment again, and he said he would gladly pay them as much as he could, and he paid them then a good hundred thousand marks. Of these hundred thousand marks the Venetians received a half, for they were to have half of the grains, and of the fifty thousand marks that remained they were paid thirty-six thousand which the French still owed them for their navy. And from the other twenty thousand marks which remained to the Pilgrims they paid back those who had loaned their money to pay for the passage.” The Venetians received most of the money, but it was nowhere near what they had expected from their puppet Emperor Alexios IV. “Afterwards the Emperor sought out the barons and said to them that he had nothing save Constantinople and that this was worth little to him by itself, for his uncle held all the cities and castles that ought to be his. So he asked the barons to help him conquer some of the land around, and he would right gladly give them still more of his wealth.” The Crusaders helped him “conquer” Thrace, and in the process more looting and destruction of the Roman people and their towns and cities occurred. Isaakios stayed in Constantinople while Alexios III went with the Latins into Thrace.

Robert De Clari blames the change in relations between Alexios IV and the Crusaders on Murzuphlus, the soon to be Emperor Alexios V Doukas. He had been freed from prison after the fall of Alexios III, and now was advising Alexios IV. Robert claims he somehow knew the advice he gave to the young Emperor: “Ah, sire, you have already paid them too much! Do not pay them any more. You have paid them so much now that you have mortgaged everything. Make them go away and dismiss them from your land.” Of course this infuriated the Latins, and “when the French saw that the Emperor was not going to pay them anything, all the counts and the high men of the host came together, and went to the palace of the emperor and asked again for their payment. Then the Emperor answered that he could not pay them anything, and the barons answered that if he did pay them, they would seize enough of his possessions to pay themselves.” Alexios IV may now have been regretting his wish to be Emperor in this way, for now he was in a perilous position between hostile Crusaders and resentful Romans.

THE ROMANS SHAMEFUL ATTEMPT TO PAY THE LATINS:

Alexios IV could not come up with the money, these were not the days of Manuel Komnenos, such sums did not just sit idle in the treasury waiting to be spent. However, the Latins were preoccupied with nothing more so than getting their money. It is hard to argue this was a crusade at all by this point, the goal was no longer to get money to get to the Holy Land, it was just to get the most money from the Romans as possible. Choniates says “no nation loves money more than this race,” and the Crusaders would not leave without every coin they could get. Thus even though there was no money in the treasury, there was always one place in Byzantine society with money – the Church. Niketas says “because money was lacking, he raided the sacred temples. It was a sight to behold: the holy icons of Christ consigned to the flames after being hacked to pieces with axes and cast down, their adornments carelessly and unsparingly removed by force, and the revered and all-hallowed vessels seized from the churches with utter indifference and given over to the enemy troops as common silver and gold. The Emperor himself was in no way incensed by this raging madness against the saints, and no one protested out of reverence. In our silence, not to say callousness, we differed in no way from those madmen, and because we were responsible, we both suffered and beheld the most calamitous of evils.” It is clear he and almost surely many other Romans as well, looked back and saw the melting of the icons and church treasures as an insult to God that lost them God’s favor. I think it was a huge mistake to give this gold to the Latins. It did nothing but give them an advantage and the Romans a disadvantage. That money could have been taken from the church to save the Empire, to be used by the Romans to recruit more soldiers and pay the Varangians. More like how Alexios Komnenos or Herakleios requisitioned funds from the Church for the good of the Romans. Instead, the confiscation created resentment and achieved no positive gains. Throughout Byzantine history the Romans took great care to stay in God’s favor as they perceived it, and this was probably a great spiritual and material pain for many Romans.

THE ALLEGED CONVERSATION BETWEEN ALEXIOS IV AND DANDOLO:

When the Crusaders still had not received the impossible sum Alexios IV had offered them, the Venetian mastermind the Doge Dandolo went to speak with the Emperor. The Emperor went to the shore on a horse, and Dandalo came near the shore on a ship and the following conversation, according to Robert De Clari occurred:

Dandolo: “Alexius, what dost thou mean? Take thought how we rescued thee from great wretchedness and how we have made thee a lord and have had thee crowned Emperor. Wilt though not keep thy covenant with us and wilt thou not do anything more about it?”

Alexios IV: “Nay, I will not do more than I have done”

Dandolo: “No? Wretched boy, we dragged thee out of the filth, and into the filth we will cast thee again. And I defy thee, and give thee well to know what I will do thee all the harm in my power from this moment forward.”

Although it sounds a bit like fiction rather than fact, it does represent the feelings of the Crusaders at this moment. They felt betrayed because they did not realize that Alexios IV offered more than he could ever pay. I am very confident this is a literary device to display the righteousness of the Latins to their audience. I am sure the Crusaders did demand their money, and clearly they did not get all of it, but why would Alexios IV risk his safety to go to the shore for such a meeting? Choniates does not record this meeting at all either.

Robert De Clari says the Romans tried to burn the Venetian fleet with fireships. Not “Greek”/Roman fire, which had been lost by now, but with ships laden with kindling, set on fire, and sailed at the enemy fleet. The Roman ships were ineffective so it was a reasonable gamble to take for the Byzantines. The Crusader historians said “while they were in such straits, what did the Emperor and his traitors who were with him do but plan a great treason” and take “ships into the city by night and have them filled with wood and have them set on fire. When it came towards midnight and the ships were well ablaze, a strong wind arose and the Greeks loosed these ships all on fire to burn the navy…” This attack, and a similar fireship attack a couple of weeks later, failed to damage the Latin ships. In this time, Robert says the Byzantines fortified the sea walls with wooden towers and platforms built on top of the sea walls to raise their height and reduce the advantage of the tall Venetian masts. The Latins busied themselves with looting the mansions of the elite around the Propontis and imperial suburbs.

THE FURY OF THE PEOPLE OF THE CITY:

The people of Constantinople were innocent victims in all this. The power-plays of the Angelos family, and the money-seeking of the Crusaders had combined in a way which left them in the crosshairs. Their city was being burned and attacked by foreigners. Then, after the Byzantines had debased their own sacred churches to pay the Latins, resentment boiled over in the imperial capital. It is important to note how God’s favor meant to the Byzantine people, look at his vicious the dispute over iconoclasm had been for example. Choniates describes the “city rabble” in a critical way as they unleashed their frustration on the residents of Constantinople who were from Western nations. They attacked and destroyed areas of the city where the residents were Italian. It may sound like revenge, but in reality this was a poor choice. It alienated the Byzantines even more. made the Romans look cruel, and fit into the Crusader moral narrative. The Pisans in particular, historical enemies of Venice, made cause with the Venetians after their quarter was razed. They had helped repel the first attacks, but now would be attacking the city with the Crusaders. Animosity between East and West was growing by the day, by the hour. The destruction in the city was about to go to levels not seen since the Nika riots, probably exceeding the damage from those events easily.

In his chronicle, Villehardouin described this final division between the Romans and the Westerners — “And the Latins, to whatever land they might belong, who were lodged in Constantinople, dared no longer to remain therein; but they took their wives and their children, and such of their possessions as they could save from the fire, and entered into boats and vessels, and passed over the port and came to the camp of the pilgrims. Nor were they few in number, for there were of them some fifteen thousand, small and great; and afterwards it proved to be of great advantage to the pilgrims that these should have crossed over to them. Thus there was division between the Greeks and Franks; nor were they ever again at one as they had been before, for neither side knew on whom to cast the blame for the fire; and this rankled in men’s hearts upon either side.” Reading all three accounts of Choniates, Villehardouin, and Robert De Clari – it seems very clear that the Crusaders did start the fire. It is a tactic they used repeatedly, and the Romans had nothing to gain trapped in their city to set a massive fire. Robert De Clari is shamelessly clear that fire was a tactic of first-resort, not last-resort.

The people also strangely took their anger out on a statue in the Forum of Constantine. Choniates says the “foolish rabble” destroyed it because her orientation and gesture seemed to be “beckoning on the Western armies.” He described the statue as “standing to a height of thirty feet and wore a garment made of bronze, as was the entire figure. The robe reached down to her feet and fell into folds in many places so that no part of the body which Nature has ordained to be clothed should be exposed. A military girdle tight cinctured her waisted. Covering her prominent breasts and shoulders was an upper garment of goatskin embellished with the Gorgon’s head[the Aegis]. Her long bare beck was an irresistible delight to behold. The bronze was so transformed by its convincing portrayal of the goddess in all her parts that her lips gave the appearance that, should one stop to listen, one would hear a gentle voice…” Choniates says the statue did not even point towards the Western armies, but the mob thought it did, “as a result of such misconceptions they shattered the statue of Athena.” It is very possible this was the Athena Promachos statue from the Acropolis in Athens. Whatever statue it was, it was one of grandeur, a true loss.

It sounds barbaric, and it was, but the context of events is important. Statue shattering was not a common event in Constantinople, which is why statues survived. However, the people were suffering and a superstitious belief the statue could somehow cause them harm would be taken more seriously at this perilous moment. The citizens were being taxed and having their wealth confiscated, some were homeless from the first fire, and yet the situation just got worse. Frustration was a natural outcome, even if this venting of it is most unfortunate.

THE GREAT FIRE OF AUGUST 19 1203