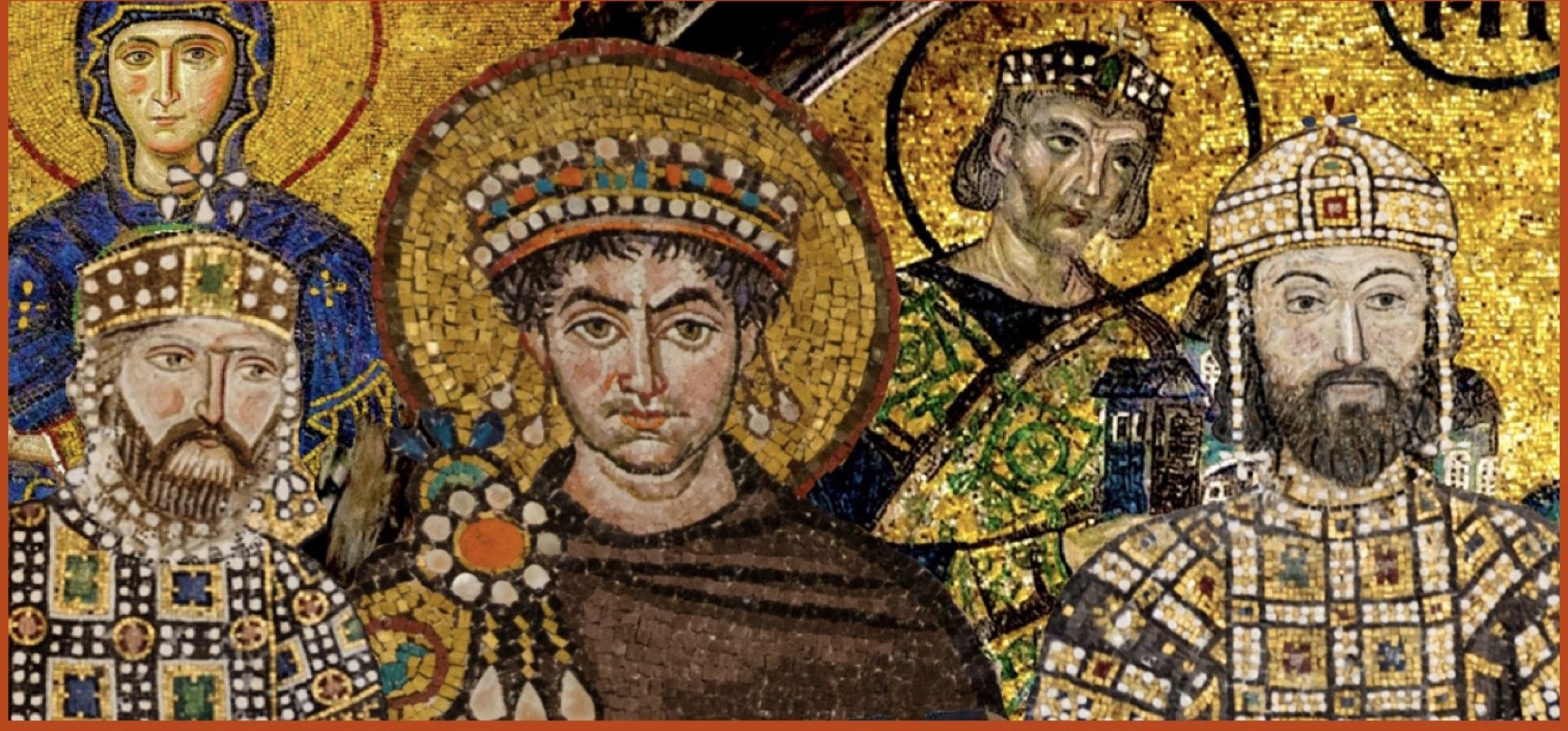

Alexios Komnenos was among the greatest Roman Emperors ever in my personal opinion, however there is one moment in his career which can certainly be described as his biggest failure. Much of the Roman army was battered and destroyed, even the fearsome Varangians were massacred. This was the battle of Dyrrhachion!

BACKGROUND:

In 1081AD the powerful Norman Duke Robert Guiscard, whom had removed the Romans from their ancient presence in Italy, now set eyes on the Balkans. Bari, the last Roman city in Italy, had fallen in 1071 to the Normans. The Romans were clearly weak, and Robert Guiscard felt they could be toppled. The new Emperor Alexios Komnenos had taken power to reverse the rapid Roman collapse since Manzikert, and he knew this had to be dealt with immediately.

One thing Alexios knew was he needed to seek a strong ally, for this he turned to the Empire’s longtime ally, the Republic of Venice. The Normans were crossing the sea, so a powerful navy could exploit that. The Venetians also genuinely shared an interest in thwarting Norman power. However, for this he had to issue a Chrysobull to relieve the Venetians of the Kommerkion, a commercial tax on trade in the Empire. In addition, the Venetians were given license to establish a Venetian quarter in Constantinople along the Golden Horn. Some criticize this harshly, but fail to see the desperation in the situation. One cannot judge Alexios as if the Roman state was not on the verge of collapse. That would be a severe underestimation of the capabilities of both Robert Guiscard as a leader and the Norman army itself.

THE SIEGE OF DYRRACHION:

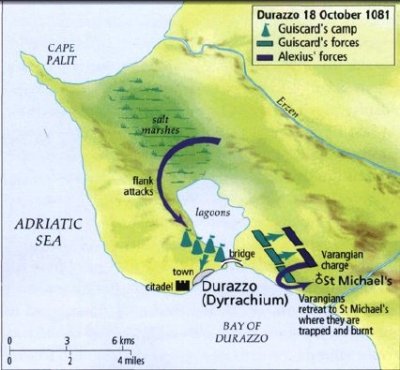

When Robert Guiscard landed, he was unopposed, no Roman army met him on the beaches like the Athenians met the Persians at the Battle of Marathon. However, the city itself was prepared. Guiscard immediately got to work and set the fortified city of Dyrrhachion under siege. John Haldon described the situation: “The city was extremely well-defended, situated on a long and narrow peninsula which ran parallel with the coast but separated from it by a brackish and marshy lagoon. The powerful defences which dated from the sixth century, had been well-maintained, and city was in a position to withstand a long siege.”

Guiscard ordered his soldiers and navy to launch a full-scale attack on the city, which was going to be a major challenge considering the defenders advantages. Before Robert could try to do this, the Venetian fleet which Alexios had brought into the conflict with his concessions arrived and defeated the Norman fleet. Now Guiscard could not attack the city by land and sea, and his chances of taking the city were lower.

To make matters worse, as the Venetians smashed the Normans in the sea the Roman defenders sallied out and opportunistically killed many Normans. Guiscard was off to a bad start. The Normans were trapped in their camp, they were now blockaded by sea, and demoralized.

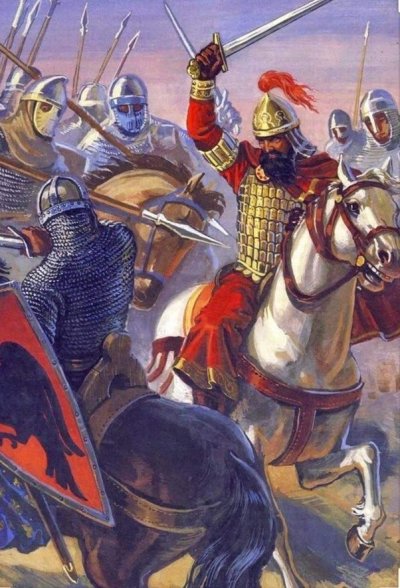

Despite the initial disaster, Guiscard was a great leader and was not finished or ready to accept defeat. He ordered siege engines to be built, and began bombarding Dyrrhachion with them. Guiscard then received news from his scouts that Alexios Komnenos was marching West with an imperial field army to Epiros to face him.

PREPARING FOR BATTLE:

As Alexios moved west, he received bad news at Thessaloniki. His informants told him that the garrison attempted another sally against the Normans and many Romans were killed. Guiscard was also constructing siege towers to up the pressure. This demonstrated the urgency of the situation, Dyrrhachion needed to be relieved.

Haldon describes the situation before the battle: “The size of the two armies is hard to assess, Anna Komnena gives a figure of 30,000 for the Norman host, consisting of a core of some 1300 heavily armed cavalry supported by lighter cavalry and a large draft of infantry and footsoldiers, some of dubious quality. The figure is, again, probably exaggerated, but it was nonetheless a very substantial force, and the emperor almost certainly had a smaller army with which to engage the Normans.”

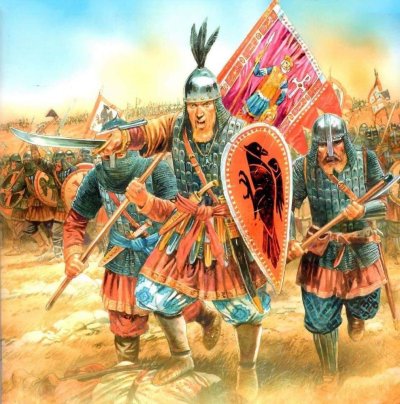

On the Roman side, Haldon says that: “Alexios had with him the Thracian and Macedonian tagmata, perhaps 5,000 strong; the exkoubita, a guards unit which may have numbered 1,000; the vestiaritai, similarly an elite unit of probably the same number, a body of Frankish knights under Constantine Humbertopoulos; the corps of the Manichaeans, consisting of two units totally 2800 men together; the various tagmata of Thessalian cavalry, whose numbers are unknown, some 2,000 Turkish allied troops from Asia Minor, along with levies from Thrace and other Balkan provinces; a corps of Armenian infantry, probably several thousand strong; the Varangians, perhaps 1400 strong; and an unknown number of light infantry archers and slingers. His total force numbered perhaps 18-20000, although it may have been slightly larger.”

The stage was set for a very large battle, both sides had a large army of over 20,000. Alexios sought council on what to do. His senior officers advised him to be cautious, as Guiscard was in the middle of a siege. Alexios did not have to rush into battle immediately. The commander of the garrison of Dyrrhachion, George Palaiologos, argued for the Emperor to wait it out.

Some officers urged Alexios to attack, and Alexios apparently believed in this option as well. It is likely he felt like he needed to be a man of action, as that was the premise of his imperial coup – to bring the Romans back to military success. The Emperor ordered his army to prepare for battle.

OPENING MANEUVERS:

The Romans moved up as Alexios ordered, “but while hoped to catch the Normans unawares and still in position around the defences of Dyrrhachion, Robert had scouts posted who informed him of the imperial army’s approach. Alexios advanced to a low range of hills opposite the Norman camp on the neck of the peninsula, preparatory to an attack on the Norman encampment the next day. His camp was entrenched along the higher ground, with the sea and the lagoon on the left…The emperor’s plan was to attack the Norman camp simultaneously from the city and from the salt-marshes, while the main force would march around the neck of the peninsula, closing it off and attacking the Normans from the rear. But Guiscard was too intelligent a tactician to allow himself, with superior numbers, to be boxed in, and during the night of 17th-18th October he moved his army out and along the peninsula, to draw it up in battle order on the mainland facing Alexios, its rear to the lagoon.”

Guiscard was not afraid of Alexios, and was eager to face him. Now, Alexios was going to have to react to Guiscard’s plan instead of being the proactive force.

GUISCARD OUTSMARTS THE ROMANS:

Alexios had already sent part of his army through the marshes to attack Robert’s camp. His main force now formed into three divisions to match the Normans. Guiscard commanded the center of his army, and Alexios the center of his. The Varangians were in the front lines of the Roman center, ready to face the Normans. The detachment of soldiers sent to attack the Norman camp found it empty and abandoned, now they were essentially a waste of manpower as they were not in the battle. Guiscard had outsmarted Alexios!

ROMANS CLOSE TO WINNING THE BATTLE:

Alexios had no choice now, despite the fact that he had sent troops to attack an empty camp, he had committed his army. He ordered an advance. The Varangians led the attack, followed by archers who could spray the enemy with arrows. The archers would move in front of the Varangians, let loose a volley of arrows, and retreat behind them. As the army slowly advanced, caution of a Norman cavalry charge, the Romans repeated the maneuver.

When the armies finally got close, Guiscard ordered cavalry from his center to charge and then suddenly retreat, intending to bait the Varangians into a reckless charge. However, all they got was arrows shot at them.

“Then the units on the Norman right under count Ami suddenly charged forward against the point where the Roman centre and left wing divisions met, directing their attack against the left flank of the Varangian line. But while the Varangians stood and stoutly resisted the attack, the Roman left wing under Pakourianos, and including some of Alexios’ best troops, surged forward and broke the Norman formation, which disintegrated.” (Haldon, The Byzantine Wars). The troops which they charged against were some of the weaker Norman soldiers, who fled towards the sea. Robert’s wife rallied some of them there and sent them back into battle.

THE VARANGIAN ERROR:

“In the meantime the Norman left wing and centre engaged in skirmishing with the Roman forces opposite, and with the Norman right broken, their centre, along with most of Guiscard’s heavy cavalry, looked in danger of being outflanked. At this point the Romans appeared to be winning the fight, but the Varangians had been unable to resist joining in the pursuit of the fleeing Norman troops, and had become separated from Alexios’s main line. Tired by the chase and by the weight of their equipment, they were in no position to resist a determined assault. Guiscard now sent against them a strong force of Norman spearmen which took them unexpectedly in the flank, and within a short time the Varangian formation had been broken up with heavy casualties. Some of the remaining Varangian soldiers fled for refuge to a small chapel which stood nearby, where the Normans shut them in and set fire to the chapel. The whole detachment perished.” The battle momentum had now changed directions. The Varangians were dead, the Normans were encouraged and inspired by the turnaround in their fortunes.

THE ROMAN COLLAPSE:

With the Varangians gone, and the left wing chasing after the Norman right wing which had retreated, the Roman formation which had initially broken the Norman line was now itself broken. The Roman center, under the command of Alexios was dangerously vulnerable now.

Robert then unleashed his signature weapon, a heavy cavalry charge against the Roman center. His elite heavy cavalry had been held in reserve, as against an enemy which is not properly organized they are brutally effective! “Divided into a number of smaller detachments, these now crashed at several points into Alexios’s line. The infantry archers and skirmishers who had been placed behind the Varangians, if they were still in position could have offered little, if any resistance to such an attack. No mention is made of the Roman right, but along with the main battle of the Roman centre, these two divisions, without their heavy Varangian infantry in the van, soon disintegrated. The emperor and his retune and guards resisted as long as they could, but were soon compelled to fall back and flee, the emperor escaping only after a long pursuit and numerous attempts had been made to take or kill him by the Norman forces, which were now able to encircle the remaining Byzantine troops at leisure. The imperial camp, with its rich booty, was left defenceless and was taken by the victorious Normans.” (Haldon, The Byzantine Wars)

The battle was a terrible defeat, “shattering the little that remained of the western tagmata” in the words of Warren Treadgold. This is hard to argue against! Haldon offers a reasonable assessment of Alexios: “Alexios was undoubtedly a good tactician, but he was badly let down by the indisciplined rush to pursue the beaten enemy wings, a cardinal sin in the Byzantine tactical manuals.” Haldon added that: “this defeat was especially seriously for an empire already so desperately short of manpower and resources, and Alexios had to start almost from scratch to rebuild his army thereafter.”

THE CASUALTIES:

The losses on the Roman side were, naturally following such a collapse of battle order, very high. Probably around 25% of the force Alexios deployed was lost, so around 5,000 men. This also included the Varangians, which were high quality and expensive warriors which could not be replaced instantly.

For the Normans, their losses are not specifically known. However, they must have also suffered reasonably high casualties in the opening stages of the battle which the Romans had dominated. As for Robert Guiscard’s heavy cavalry, allegedly only 30 of them fell in their glorious charge that broke the Roman army into pieces.

AFTERMATH & THE END OF AN ERA:

Alexios went on defeat the Normans on more than once occasion, and secure the Balkans, as well as begin the liberation of Anatolia. But the consequences of this battle were very significant nonetheless. In the words of Warren Treadgold: “Alexios I took over in 1081 with only the rump of an army and the broken shell of Asia Minor. To repel the Norman invasion of the Balkans, he withdrew the last effective troops from Anatolia, giving up most of the empire’s remaining outposts there. Then he lost most of what remained of the army fighting the Normans at Dyrrhachium.”

Although Alexios really had no choice to do this, and as Treadgold admits “in time Alexios I put together a new army.” However, “he did not and could not replace the large professional force of native troops that Byzantium had inherited from the Rome, maintained for so long, and thrown away in the course of the 11th century.” Haldon is a bit more fair to Alexios, crediting him for his achievements: “It is remarkable that, with in a few years, he had succeeded so far as to be able to throw the Normans out of the Balkans and defeat the Pechenegs and Seljuks.”

Though the Roman army in the 12th century did have native troops, and did succeed in the battlefield, it was never as institutionally powerful as it was before. It was reliant on competent imperial direction, which ended in 1180 after the death of Manuel I Komnenos. Essentially, the new army was only as good as its Emperor. I do think what needs to be remembered was Alexios kept the Empire not just alive, but powerful and wealthy. Much of Anatolia was recovered. I think he learned from Dyrrhachium and rebuilt the Roman army as much as was possible.

The trade concessions to Venice also had long-term consequences, though I think failure to change the situation should rest more on Manuel I Komnenos than Alexios, who was under great duress. Manuel had far more power and free reign to deal with it, but failed to do so and instead made tensions higher with no gain for the Romans.

SOURCES:

Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium by Jonathan Harris

The Byzantine Wars by John Haldon

Byzantium and the Crusades by Jonathan Harris

Warfare, State, and Society in the Byzantine World 565-1204 by John Haldon

Byzantium and Its Army 284-1081 by Warren Treadgold