In 1397 when Constantinople looked like it might fall, Manuel II Palaiologos prayed: “Lord Jesus Christ, let it not come to pass that the great multitude of Christian people should hear it said that it was in the days of Emperor Manuel that the City, with all its sacred and venerable monuments of the faith, was delivered to the infidel.” The city had been blockaded for three years, and the Romans did not have the army to fight the Ottomans in the field.

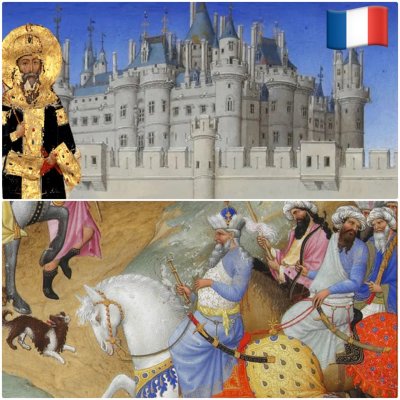

To save Constantinople during his time, he went on a grand mission to Western Europe which was unlike that of any other medieval Roman Emperor. On December 10 1399, Constantinople was blockaded, the people were suffering. A ship slipped out of the harbor with the Emperor Manuel II on board: “One wonders what Manuel’s thoughts were as he watched the towers of his capital fade into the distance” as he set out as far as France and England to save his empire!

Not many emperors could leave Constantinople for long, especially not without being in command of an army which demonstrated their power. However, Manuel II must have felt secure and those around him must have respected the necessity of this diplomatic mission. He would not see his family for years. The only company Manuel wanted was his most experienced diplomats with knowledge of the westerners and their way of thinking.

First, he arrived at the Peloponnese, in an area of the Empire known as the Despotate of the Morea. Here, he had to essentially beg the Venetians for passage to Italy. “On February 27 (1400), the senate allotted him galleys and funds.” Some of his relatives were even offered future asylum in case the Ottomans conquered his lands in his absence. The situation was dire, the imperial family seriously contemplated a future without a Roman Empire in existence

This trip was a “novel diplomatic tactic.” While John V had visited Rome before, Manuel would be going far beyond that to lands not visited by a Roman Emperor since antiquity. No Eastern Roman “emperor had ever undertaken a European ‘tour’ before. By embarking upon this tour of several cities, France and England, Manuel was essentially presenting himself as a diplomat-emperor.”

He made a positive personal impression. Pretty much all the western sources saw “Manuel’s wisdom and regal bearing.” This makes sense, he was a very well-read and well-educated man. The real question was…would Manuel’s mission “persuade the Western rulers to aid Constantinople?”

Manuel had to convince the foreigners his own people would fight. Some feared his regent, John VII Palaiologos might cowardly surrender Constantinople to the Ottomans. Even Manuel took note in his writings of “John’s inclination towards surrendering.” Clearly despite some doubt Manuel II trusted him enough while he was gone.

Manuel tried to give gifts out to men to show his generosity and piety. In Milan, he not only met his old “friend Manuel Chrysoloras…but was welcomed into the city by the Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti. The emperor presented the duke with a thorn from the crown of Christ, as well as an icon of the Virgin.” No help would ever come from powerful Duke Visconti though, unfortunately for the Romans.

His next main stop was Paris, “on 3 June, Manuel reached Charanton near Paris where he was welcomed by nearly 2,000 of the city’s citizens who had gathered to see the Byzantine emperor.” After the officials exchanged pleasantries, “the king himself arrived. The two rulers exchanged a peace kiss & Charles IV presented Manuel with a white horse; the emperor delighted the crown by mounting it.” Manuel impressed visually wearing white silk with “flowing white hair and a beard.” There was a banquet in Paris where Manuel dined with the royal family and Manuel stayed in the Louvre. From France Manuel sent out messages soliciting aid “to Aragon and Castile, as well as with Navarre.” The gifting of relics to various courts in Europe amplified the attention of his visit.

The majority of Manuel’s mission was spent staying at the Louvre in Paris. He took part in hunts, banquets, celebrations, as well as networking. He spent time in-person with many French noblemen and high-ranking clergy, he even attended royal weddings. But, he didn’t get the military help he needed.

It is interesting that while Manuel was in Paris “Charles VI had one of his episodes of insanity. In these moments of crisis, Charles was completely secluded, refusing to eat, sleep, or see anyone.” It is likely that these episodes of madness motivated a trip to England as he realized the madness of Charles, and sought another king to ask for help!

It is truly remarkable that a Roman Emperor visited England in the 15th century. He was the first Roman Emperor to do so since the 4th century! But the situation was dire in Constantinople, so times were different. “Because of the attacks of the despicable Turks, we came to these western territories & to other Christian lands.” Such were the circumstances that brought Manuel II to far away England to visit King Henry IV. After a long but ultimately fruitless stay in Paris, Manuel II Palaiologos left the Louvre and went to Calais in October 1400. In December, he crossed the English Channel. After dealing with some storms during a challenging crossing, he was welcomed on December 13 in Canterbury

“On December 21, the Emperor met with Henry IV in Blackheath. The two rulers then proceeded to London. There, twelve of the aldermen of the city and their sons performed a masquerade for Manuel” in honor of his arrival. Wherever he went, people were curious and eager to see him. It seems like it was akin to a celebrity being in town. It was not a once in a lifetime event, it was a one-time ever event.

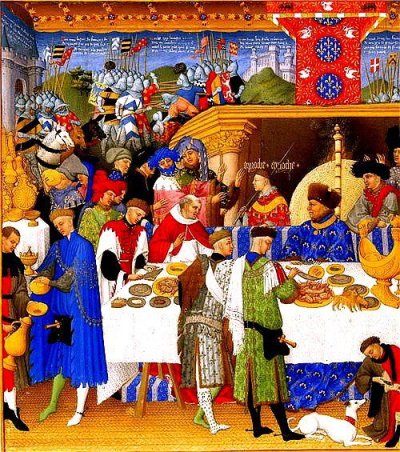

The Emperor of the Romans and the King of England then shared Christmas together, with King Henry IV hosting a grand feast at the Eltham Palace. Just as Emperors in ages past had hosted races in the hippodrome for their guests, Henry held a jousting tournament for guest.

Unfortunately, “no details of this occasion have survived, but since feasts were also political occasions to impress, it must have been quite a sight. ‘Subtleties’ – models of castles and ships and animals made of food, would have been paraded, and live birds may have been hidden in pies.” The English King only got one chance to impress a Roman Emperor!

What might the two rulers have eaten? A menu from Henry’s coronation included “meat in pepper sauce, a boar’s head and tusks, pheasants, cygnets, sturgeon, jelly, peacocks, roast venison, tarts, quails, glazed eggs, and an eagle.” It was likely rather similar on this occasion.

Unlike “his silence on Charles VI, Manuel writes a laudatory portrait of Henry IV in his sole surviving letter from London.” He even called him “the ruler of Great Britain, or one might say, the second oikoumene.” It is clear he held Henry IV in high esteem and saw him as virtuous

“While Manuel’s praise of the king was certainly based on the lavish promises Henry made to him” – his stay was truly nice and enjoyable. Manuel appreciated the English King. “As a token of gratitude, the emperor gave Henry a piece from the Seamless Tunic of Christ…Henry cut it in two to give one piece to the Archbishop of Canterbury.”

The English “were particularly interested in the Orthodox rites that the Byzantine party observed, as well as their long uniform clothes and flowing beards.” Surely Orthodox Christianity would have seemed more distant and foreign to them compared to say Italians, for example. Most in England had likely never seen an Orthodox person. It also must have been a strange experience for the Roman priests and the entourage of Manuel II.

Adam of Usk, after remarking on the piety of the visitors write: “I thought to myself how sad it was that this great Christian leader from the remote east had been driven by the power of the infidels to visit distant islands in the west in order to seek help against them.” It is likely Manuel got much sympathy for his situation from most people he encountered.

London was a growing city in this era, and Manuel would have seen many intriguing things. “Undoubtedly, he would have seen the Tower and London Bridge. Westminster Hall, whose roof had been recently rebuilt by Richard II, was the largest hall in Europe at the time.” It was the opposite of Constantinople, which had many grand old buildings but little in the way of new ones.

Despite how fascinating this event was, and even the most likely genuinely good intentions of the King, “the internal problems faced by Henry IV would eventually prevent him from assisting Constantinople.” It is fairly clear that Manuel put every effort into this great adventure. Manuel had been in London for two months, and returned to Paris in February 1401. Manuel then took part in a Latin mass in the Abbey of St. Denis. I wonder how his Orthodox entourage felt seeing him take part. Though perhaps this important political mission convinced them.

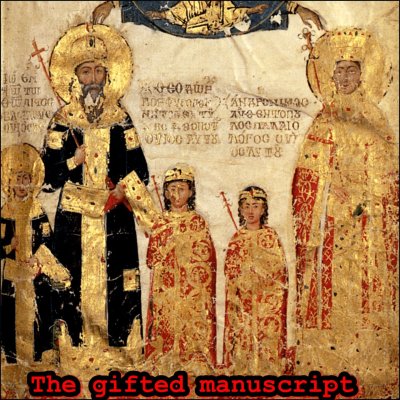

At St. Denis Manuel II “may have also seen a 9th-century manuscript of Dionysios, which had been donated by the Byzantine emperor Michael II.” Manuel II later gifted another manuscript with the “famous portrait of the imperial family.” It has been theorized this a “sequel” to the older text, sent to be a companion to it.

“In one of his letters, Manuel enthusiastically spoke of plans to assemble a joint army of French and the English…He was to be sorely disappointed.” It was a fantasy. No military aid was to come to Constantinople, instead the French and English would fight each other in 1415. It was not the right time for such a thing.

However, instead “Byzantium was momentarily saved by the ‘miracle of Tamerlane’” – the Ottoman defeat at the battle of Ankara (1402). His empire would go on, and on June 9 1403, he “entered Constantinople. The emperor was home at last.”

For now, Constantinople was safe! Manuel II had his wish not to be the Emperor who lost Constantinople. Although he got his wish, it was his very own son Constantine XI who would have to bear that burden, and for that he is more well-remembered than Manuel II Palaiologos. Constantinople would be under siege again during his reign in 1422 as well.

Source:

Manuel II Palaiologos: A Byzantine Emperor in a Time of Tumult by Siren Çelik