Trebizond is an interesting city in the Byzantine world, in most part due to the fact it took its own trajectory in the last few centuries before the Ottomans. It was the greatest city in the area of Pontos. It played a very unique role as the center of a Byzantine state separate from the rule of Constantinople. An independent Trebizond was able to outlast the Seljuk threat, the Mongol threat, and even outlast Constantinople. Constantinople fell in 1453 where as Trebizond lingered on, albeit with doom on the horizon, until 1461.

EARLY BYZANTINE HISTORY

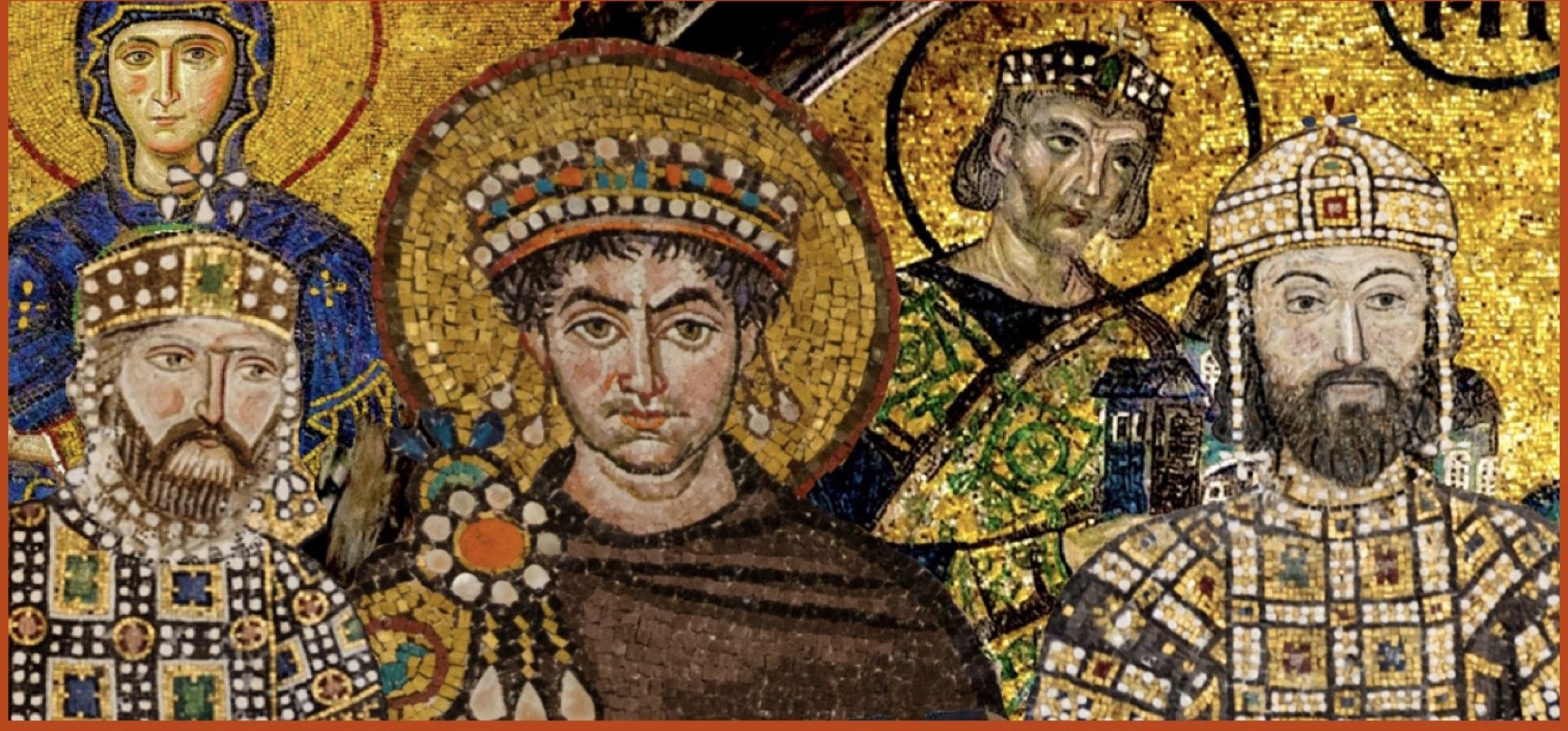

In Late Roman and early “Byzantine” history the city was not particularly impressive nor important. Diocletian had to rebuild after Goths had crossed into Anatolia during the 3rd century and ravaged the undefended cities. Justinian had assigned as part of the administration Roman Armenia in the 6th century. In the 7th century it became part of the Armeniakon Theme as the Roman provincial system was reorganized into the Theme system. The city of Trebizond was awarded an archbishopric in the 8th century. In the early 9th century, it became part of a Theme of Chaldia.

ANARCHY IN ANATOLIA AND THE BEGINNINGS OF INDEPENDENCE:

After the battle of Manzikert in 1071, Trebizond became a mountain refuge in Anatolia as the rest of the area rapidly fell to the Turks over the following decade. The Turks briefly captured the city, but it was then able to be secured by the Gabras family which ruled it independently but with a token submission to the Komnenian Emperors. The independent trajectory of Trebizond started at this time, as the Komnenian Emperors struggled to assert their authority over such a faraway province. It would be expensive and dangerous for an Emperor to march all the way to Trebizond.

But John Komnenos did just that, he marched his army to fight against the Turks and also stopped by Trebizond in order to secure the city under firm central control. This is why John was such an excellent Emperor, he was willing to march out and set targets and achieve them systematically, something Manuel was not quite as good at.

Less than a century later, this independence would be full and permanent in the buildup to and aftermath of the Fourth Crusade. Trebizond would never reconquer Constantinople, that honor fell to the Emperors of Nicaea whom were recognized as the true Roman Emperors. The story of Trebizond is an interesting one which runs parallel to proper Byzantine history.

HOW DID THE EMPIRE OF TREBIZOND FORM?

Unlike the the Empire of Nicaea or the Despotate of Epirus, Trebizond was not a state formed in reaction to the Fourth Crusade. It was already an effort in progress to seize Trebizond and Pontos from the authority of Constantinople before the Crusaders began dividing the treasures amongst themselves. The chaos which led to the Fourth Crusade being successful in taking Constantinople did contribute to this event

A PLOT TO RETURN:

The Komnenos family had overseen the Komnenian restoration, which had seen Byzantine revival as a major power, but it all came apart under Andronikos Komnenos. Andronikos murdered Manuel’s son and rightful heir, the boy Alexios II Komnenos. Andronikos was later killed himself for his terrible deeds, but he had his own son(confusingly also named Manuel, but not the Emperor). It was his grandsons, two brothers named Alexios Komnenos and David Komnenos who would take over Trebizond. They felt that they were the rightful rulers of the Roman Empire.

GEORGIAN INTERFERENCE:

A SMALL TOWN:

The city of Trebizond which was taken by the Komnenian family was not much to brag about. In the Oxford History of Byzantium it was described: “In 1204, Trebizond consisted of a small fortified enceinte(a citadel) on a steep hill, with market, harbor, suburbs, and separately fortified monasteries outside the walls. Much of it was exposed to Turkish attacks.” In otherwords, this was not like the city of Nicaea – it did not have a large area enclosed by sturdy walls. It was not a readymade capital city, but the Komnenians of Trebizond would build it up.

FORGING AN IMPERIAL CAPITAL:

Anthony Eastmond offers some good insights into how the city was developed by the Emperors, as well as what it was like: “For their capital, the emperors chose well. Trebizond was an easily defended city, in a well-protected land. Its rulers made the most of the natural lay of the land, building their palace in the formidable citadel between the two ravines that divided the city. Here they lived in splendour in a lavishly decorated palace that attracted wonder from visitors. Over the centuries, they extended the city walls down from the citadel to the shoreline, joining the heart of the city to the harbour created by the Roman Emperor Hadrian in the second century AD. Throughout the city they built churches to honour the precious relics and miraculous icons that the city preserved.”

Eastmond continued: “The cathedral of the Panagia Chrysokephalos stood in the middle city and the principal cult church of St Eugenios overlooked the city from the east ravine by the commercial heart of the city, around the Daphnous harbor and the central square, the Meydan. It was here that Venetian and Genoese merchants established their warehouses and castles. Looking down on them all was Mount Minthrion, where a number of religious foundations were established, including the nunnery of the Theoskepastos and the monastery of St. Sabbas. Further afield were the monasteries of the Matzouka, notably Soumela and Vazelon, received lavish funding from the Emperors to match their extraordinary cliff-face locations; and in 1374 Emperor Alexios III financed the building of Dionysiou monastery on Mt. Athos, where his memory is still treasured today.”

Ironically, the most famous church of Trebizond, was not really inside the city. Anthony Eastmond pointed out that: “The Hagia Sophia (of Trebizond) stood somewhat apart from the city to the west, and until the mid 1960’s it was surrounded by fields as it must have been throughout the Middle Ages. All are testimony to the piety of the Christians of Trebizond, the wealth that they derived from trade passing through their city, and the silver mines they were able to exploit.”

WHY DID TREBIZOND SURVIVE?:

The Turkmen, which are essentially decentralized bands of nomadic Turkic warriors, were the main cause of the collapse of the Byzantine holdings in most of Anatolia. Anthony Bryers pointed out that: “where there was the will to resist, backed by local autonomy, leadership, or identity, and coupled with the restraints of a centralized state, no Turkmens were in a position to surmount it. So the most substantial Turkmen expansion in western and northwestern Anatolia followed the coincidental transfer elsewhere (in different ways and to different extents) of two great centralized and local Anatolian governments: the Seljuk state to the Mongols after 1243(and more definitively after 1277), and the ‘Empire of Nicaea’ to Constantinople’ after 1261.”

The Empire of Nicaea had been able to defend itself and expand even when surrounded by enemies. Nicaea is arguably the ideal example of the kind of government needed to deal with the Turkmen. Nicaea was near the Turkish frontier, the Emperor could react quickly. Incursions by Turkic nomads was not a far away problem, it needed to be dealt with immediately. And it was, successfully.

The Seljuks had been able to hold together large swaths of territory under relatively stable conditions as well. Bryers noted in his article that “the coefficient between the decline of centralized government and the spread of pastoralism is familiar enough, but what is striking is not the evaporation of Byzantine authority in western Anatolia and its subsequent supplanting by seven emirates of more or less Turkmen origin, within half a century of the loss of its local government in 1261, but the survival (until 1390) of the one enclave there which had local autonomy and wished to keep it: Philadelphia(Alasehir).”

15TH CENTURY:

By the 15th century, despite having majority Christian populations in most of coastal Asia Minor, the world was closing around Trebizond. There was no hope Constantinople could reassert any control over Anatolia, and Trebizond did not possess the strength needed to expand either. The city had always been small as well, however prosperous. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, it only had a population of 4,000 in 1438. This is far less than the population of Constantinople even at its lowest times. However, it proceeded to survive in a world increasingly dominated by Turkic peoples until 1461.

ECONOMY OF TREBIZOND:

Trebizond is known for its prominent role in the Black Sea trade economy. Definitely this made the city wealthier, and connected to the Italian maritime trade republics. But, much like Constantinople, despite the fact that we picture rich trade emporiums, the Emperors received most of their income from the land taxes of their realm.

However, Trebizond was much smaller, and did likely get a higher percentage of its state income from trade taxes, known as the kommerkion. Another key point is that Trebizond was able to maintain its role in trade better Constantinople did in the final era.

Anthony Bryers wrote in The Estates of the Empire of Trebizond that: “By Byzantine standards, the kommerkion of Trebizond was probably disproportionately large. Half the salary of the former strategos of Chaldia had come from the kommerkion; and unlike their Constantinopolitan cousins, the Grand Komnenoi managed to retain a declining percentae of trading profits(about 6%) until the end in 1461. I estimate, that in a busy year, as much as 20-30% of their revenue may have come from the kommerkion, of which most would have been paid by local, rather than foreign merchants. A little of the remainder of an annual income, in the possible range of 1,250,000-3,250,000 aspers in the 14th-15th centuries, came from such sources as the profits of justice, imperial trade and mining, confiscations and even piracy. Nevertheless up to three quarters came from land — either directly from the imperial estates or indirectly from taxes and tithes from other lands.”

So there we have it, yes trade was extremely important, but it was the main source of imperial income. The strategic location itself even seems overstated. The port was not of an exceptional quality, and even the Italian traders always looking to make a profit did not see it as a great opportunity in the 13th century. For example, the Genoese chose to open up their own trade post at Phadisane, a small town west of Trebizond. In reality, the independence of Trebizond and its autonomy gave it the power to survive, but also made doing business there complicated for traders looking to avoid paying taxed and trade duties.

Italians played a huge role in the economy in the 14th and 15th centuries though. Emperor Alexios III Komnenos actually took a huge loan from Genova, which was never paid back due to the fall of Trebizond in 1461.

Anthony Bryers believes the true wealth of Pontos in this period came from its rich agriculture, as well as mining resources. Based on early Ottoman data, the land was very profitable. There were was also access to timber for ships, pasture lands for animals, as well as wine and olive oil to export. Monasteries made huge sums selling wine. Two monasteries, the Pharos and the Chysokephalos, derived 82% and 87% of their income respectively from wine. Alexios IV in 1418 paid part of an indemnity to Genoa after a war in kind by giving them a huge quantity of wine.

The economy was crucial to the value of the state to the people of Pontos. These rich lands also compelled local elites to have a vested interest in the state surviving, as Turkish conquest would entail losing these estates. Thus local resistance against outsiders remained strong. If the economy does not work for the locals, then the buy-in to the state being necessary is weaker.

Thanks for reading this article, please check out my articles on Constantinople and other Byzantine cities!

SOURCES:

Greeks and Turkmens: The Pontic Exception. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 29 by Anthony Bryer

Empire of Trebizond and the Pontos(Collected Studies)

The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium

Byzantium’s Other Empire: Trebizond by Anthony Eastmond