A LOST TREASURE:

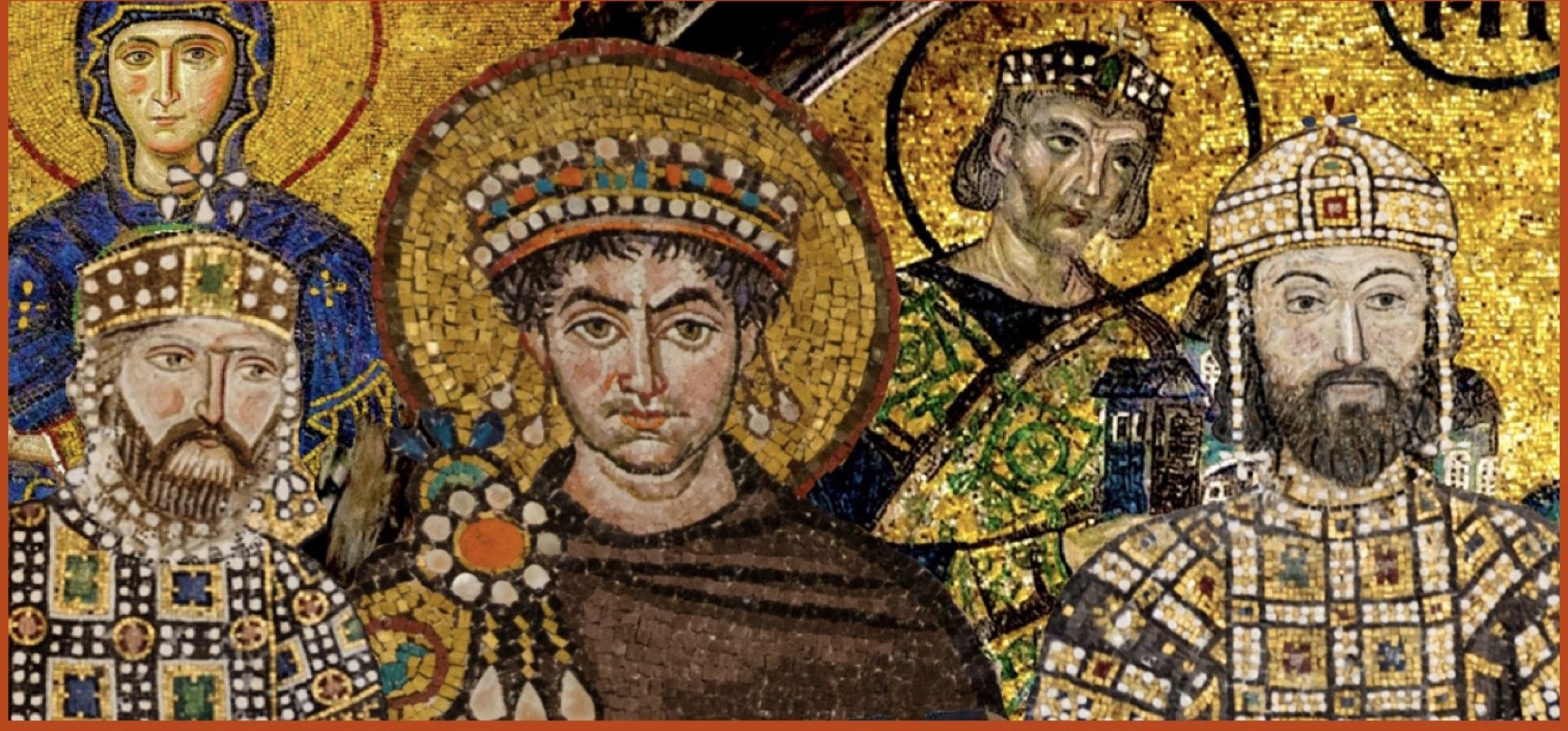

The Holy Apostles was one of the oldest and most prominent Churches in Constantinople on the highest hill of the city. The Church has a long history, as it was in existence from 330AD until the 1461, which is 1131 years! That alone is a testament to it’s importance. At one time it was, along with Hagia Sophia, one of the premier churches in the city. It was likely the second largest Church of the city as well. Nikoalos Mesarites in his description of the Church wrote about its prominent location, saying that “the first and greatest praise of this Church is that it is rich in possessing such a site and that it occupies the place of the heart in relation to the whole body of the Queen of Cities.”

I think it is extremely important to preserve the legacy of this structure and its religious and political significance. Hagia Sophia still exists to remind us of its splendor, even if it is not the same as it once was. One can see it and imagine the Byzantine era, and still appreciate it’s current form. However, the Church of the Holy Apostles is gone, so it requires a more conscious effort to maintain the memory of it. This church was founded by Constantine when he founded Constantinople, and contained his mausoleum. Thus it was not just a mausoleum of Emperors, it was a mausoleum of the founder of Constantinople, and indeed the founder of the Christian Roman Empire which the Eastern Romans carried on. After his death it created a tradition of imperial burials that lasted until the Holy Apostles was full in the 11th century and other sites had to be chosen to imitate it. It was a structure representing the eternal nature of Byzantine imperial power that one could visibly see there.

DESCRIPTIONS OF THE HOLY APOSTLES:

I have compiled some primary source descriptions of the Holy Apostles in order to bring it’s richness to light. These are descriptions of the Church itself, there are also long descriptions of the mausoleums later in the article. Perhaps the most intriguing descriptions are those of Nikolaos Mesarites. He was a Roman born in Constantinople in 1163 or 1164, of a family which belonged to the aristocracy of the court.’ His description of the Church of the Apostles was written at some time between 1198 and 1203, thus immediately prior to it being despoiled by the Latins. He starts the description off by stating that “the first and greatest praise of this Church is that it is rich in possessing such a site and that it occupies the place of the heart in relation to the whole body of the Queen of Cities.” Mesarites wrote that about the timeless legacy of the mausolea, that “Emperors from time immemorial” had cherished it as “a prized possession, wherefore they chose this place for their unbroken sleep and their rest until the time of resurrection, and this was considered by them a beloved dwelling, desired and cherished, second only to the truly beloved dwellings of the Lord of hosts, when their souls had left them and had been taken to their everlasting homes.”

The church was known for the towering view one could have from it, due to its location at a highpoint in the city. Mesarites describes the wonders one could see from the Holy Apostles. “A man who walks about in the upper galleries of the Church enjoys a varied pleasure as he gazes over the backs of the northern and southern seas. For one can see from there the sea, which itself lies there tranquilly and on its back bears freight-ships before a fair breeze, a sweet sight to all men and a source of rejoicing and pleasure. And neither is he frightened by the floods which the sea is wont to spew up, now here, now there because he stands at a fitting distance from it nor does he hear the groans of the sailors or the cries of drowning men. How much and how wide is the open country which he sees beyond the walls, which has been given its present name because men love to visit it for its great beauty and pleasantness, what description can portray in words? See, the ruler has gone out for the salvation of his people and he is staying in the Emperor’s Tents, which are opposite the palace and a little distance from it, and are built on this [land] ; for from ancient times, it has been the custom for the Roman army to gather first on this plain, as though coming from diverse springs in lands everywhere into one meeting of the waters, and when it has formed one river which will sweep aside everything that comes in its way, to set out against the enemy from this spot, for the place is sufficient for all kinds of maintenance for numberless armies. And at that time the whole army can be seen by a man standing on the parapets and the towering outlines of the Church.”

Mesarites describes the sound and impressive construction of the church as well: “This Church, O spectators, is in its great size the greatest and in its beauty the most beautiful, as you see, and adorned by its great artistry and brilliancy, is an indescribable loveliness, an unimaginable creation, a work of art of human hands surpassing human thought, visible to the eye but incomprehensible to the mind. It does not please the senses more than it impresses the mind. For it fills the sight with the beauty of its colors and by the golden gleam of its mosaics, and strikes the intelligence through its surpassing size and skillful construction. There support and hold up this hall, which can really be called the dome of Heaven since the Sun of Justice shines in it, the light which is above light, the Lord of Light, Christ, four arches, which are, so to speak, Atlas-like pillars and arms, taking their intervals from one another in the form of a four-sided figure with equal sides, and deriving the strength of their construction from the firmness of the whole figure.”

When the Crusaders found it in 1204, not too long after the description by Mesarites, it was clearly still in a pristine condition. Robert De Clari described the church: “Elsewhere in the city there another church which was called the church of the Seven Apostles. And it was said to be even richer and nobler than the Church of Saint Sophia. There was so much richness and nobility there that no one could recount to you the richness and nobility of this church. And there lay in this church the bodies of seven apostles. There was also the marble column to which Our Lord was bound, before He was put on the cross. And it was said that Constantine the emperor lay there and Helena [Constantine’s mother], and many other Emperors.” Robert did not even try to describe it, probably no burial place he had ever seen was remotely comparable.

THE IMPERIAL MAUSOLEUM OF NEW ROME:

Constantine reinvented Rome as a Christian capital, and endowed it with many classical Roman elements. He built mighty walls, a forum, renovated the hippodrome of Byzantium, added countless statues and ancient spolia, a triumphal column, a senate, and more. However, Constantine also needed a worthy burial place for his New Rome. The Holy Apostles was the solution to that.

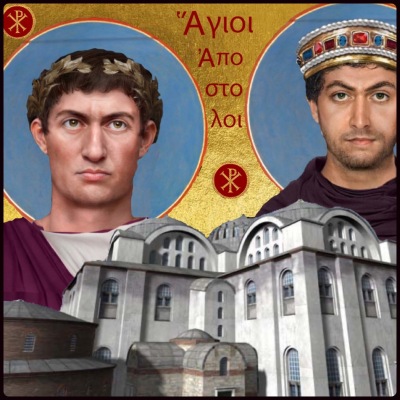

Mark Johnson, Professor of Ancient and Medieval Art at Brigham Young University described the importance of the Holy Apostles in the Cambridge Companion to Constantinople: “The most significant burial monument in the city was the church of the Holy Apostles, begun a few years before Constantine died in 337. In planning his eventual final resting place the emperor had the example of other late Roman imperial mausolea, which were largely domed rotundas, but the added consideration that his would be the first such monument for a Christian ruler. His solution was to adopt the basic architectural form of the mausolea of his immediate predecessors and combine it with the emerging idea of the Christian commemorative structure….As described by his biographer Eusebius, Constantine ordered that his sarcophagus be placed in the church that was not only dedicated to the Apostles but also possessed memorials to the Twelve, perhaps intended from the beginning to contain their relics. In so doing, he expressed the desire to share the benefit of services and the prayers that offered there. Although the form of the building has been debated, there is enough in Eusebius’ description to permit the building to be interpreted as a domed rotunda, like other imperial mausolea. It is probable that it was a double-shell structure with a tall domed core surrounded by an ambulatory with niches, similar to the design of Constantine’s daughter Constantina’s slightly later monument in Rome.”

The rotunda built by Constantine became a dynastic mausoleum for Constantine and his heirs after he died. The church itself received upgrades during the reign of Constantine’s son Constantius II. The memorials for the apostles which Constantine had put there were moved to a new cruciform addition, and Constantius had himself buried there. Other Emperors followed this tradition, which was what led to the Holy Apostles evolving into the imperial mausoleum of the Eastern Roman Empire. Famous Emperors such as Theodosius the Great, Marcan, Leo the Thracian, Zeno, and Anastasius were buried in sarcophogi of rich stone inside the rotunda of Constantine. The early Emperors had the luxury of being buried in porphry sarcophogi, some of which still exist in modern Istanbul.

After the rotunda of the Constantine, numerous other additions were incorporated into the Holy Apostles. Mark Johnson says the “so-called ‘North Stoa’ held the sarcophagi of a few late fourth-century Emperors, probably Julian (361-3), Jovian (363-4), and Valentinian (375-92). The ‘South Stoa’ seems to have been built by Arkadios (377-408) and contained his sarcophogus, along with those of his wife Eudoxia (d. 404) and their son Theodosios II (408-50). Justinian rebuilt the cruciform church in the sixth century, replacing it with another building of the same plan but covering its crossing and each arm with domes. He also added his own mausoleum in the sixth century, a cruciform structure attached to the north arm of the church, where he, his wife Theodora (d. 548), and many of their successors were interred.” These mausoleums contained the majority of Roman Emperors and many of their wives until the 11th century, as well as the remains of Saint John Chrysostomos, which were brought to the mausoleum in 437 by Theodosius II.

We actually have the writings of an Emperor, Constantine VII Porphyrogennitos, describing the mausolea in the late 10th century. In The Book Of Ceremonies, in Chapter 42 of Book II entitled “Concerning the tombs of the Emperors which are in the Church of the Holy Apostles.” Describing the heroon of Constantine the Great the Porphyrogennitos wrote: “First, to the east, lies the sarcophagus of St Constantine (I), porphyry, that is, Roman, in which he is laid with Helena his blessed mother; another sarcophagus, porphyry, Roman, in which is laid Konstantios (II), the son of Constantine the Great; another sarcophagus, porphyry, Roman, in which is laid Theodosios (I) the Great; another sarcophagus, green hieracite, in which is laid Leo (I) the Great; another sarcophagus, porphyry, Roman, in which is laid Marcian with his wife Poulcheria; another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid the emperor Zeno; another sarcophagus, Aquitanian, in which is laid Anastasios (I) Dikoros with Ariadne his wife; another sarcophagus, of green Thessalian stone, in which is laid the emperor Michael (III), the son of Theophilos. There is “another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid Basil (I) with Eudokia I and Alexander his son; another sarcophagus, Sagarian, that is, Pneumonousian, in which is laid the famous Leo (VI) with his son Constantine (VII) Porphyrogennetos who died later; another sarcophagus, white, known as Basilikion, in which is laid Constantine, the son of Basil (I); another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid St Theophano, the first wife of the blessed Leo {VI), with Eudokia, her daughter; another sarcophagus, Bithynian, in which is laid Zoe (Zaoutsina), the second wife of the said Leo; another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid Eudokia, surnamed Baine, the third wife of the said lord Leo; another sarcophagus, Proconnesian, in which are laid Anna and Anna, daughters of the blessed Leo and Zoe (Zaoutsina); another small sarcophagus of Sagarian stone, that is, Pneumonousian, in which is laid Basil, the brother of Constantine Porphyrogennetos, and Bardas, the son of Basil (I), his (Constantine’s) grandfather; another small sarcophagus of Sagarian stone in which is laid”…(missing lines follow)

Moving on the the Mausoleum of Justinian the Great, the Porphyrogennitos said: “Towards the conch itself, to the east, the first sarcophagus, in which is laid the body of Justinian, of a strange and unusual stone of a colour midway between Bithynian and Chalcedonian, very like Ostrites stone; another sarcophagus of Hierapolitan stone in which is laid Theodora, the wife of Justinian the Great; another sarcophagus, lying to the west, to the right side, dappled rose in colour, Docirnian, in which is laid Eudokia, the wife of Justinian (I) the Great; another sarcophagus, white Proconnesian, in which is laid Justin the Y ounger; another sarcophagus, of Proconnesian stone, in which is laid Sophia, the wife of Justin; another sarcophagus of white stone, Docirnian onyx, in which is laid Herakleios (I) the Great; another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid Fabia, the wife of Herakleios; another sarcophagus, Proconnesian, of Constantine Pogonatos;5 another sarcophagus, of green Thessalian stone, in which is laid Fausta, the wife of Constantine Pogonatos; another sarcophagus, Sagarian, in which is laid Constantine (IV), a descendant of Herakleios (I), son of Constantine Pogonatos; another sarcophagus of variegated Sagarian stone, in which is laid Anastasios (II), also called Artemios; another sarcophagus, of Hierapolitan stone, in which is laid the wife of Anastasios, also called Artemios; another sarcophagus, of Proconnesian stone, in which is laid Leo (III) the Isaurian; another sarcophagus, of green Thessalian stone, in which was laid Constantine (V), the son of the Isaurian, surnamed Kavallinos, but he was removed by Michael (III) and Theodora and his wretched body was burnt. Likewise, too, his sarcophagus was removed and sawn up and used in the construction of the Church of the Theotokos of the Pharos. Indeed, the large slabs which are in the said Church of the Pharos are from the said sarcophagus. another sarcophagus, of Proconnesian stone, in which is laid Irene, the wife of Constantine Kavallinos; another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid the wife of Kavallinos; a sepulcher of Proconnesian stones, in which are laid Kosmo and Irene, sisters of Kavallinos; another sarcophagus, Proconnesian, in which is laid Leo (IV) the Khazar, son of Constantine Kavallinos; another sarcophagus, of Proconnesian stone, in which is laid Irene, the wife of Leo the Khazar; another sarcophagus, green Thessalian, in which is laid Michael (II) the Stammerer; another sarcophagus, of Sagarian stone, in which is laid Thekla, the wife of Michael the Stammerer; another sarcophagus, of green stone, in which is laid the emperor Theophilos; another small sarcophagus, green, in which is laid Constantine, the son of Theophilos; another small sarcophagus, of Sagarian stone, in which is laid Maria, the daughter of Theophilos.“

Constantine VII describes some other stoas in the church as well. A stoa in the south of the church itself held the “sarcophagi of Arkadios, his son Theodosios (II), and Eudoxia his (Theodosios) mother. The tomb of Arkadios is towards of the south and that of Theodosios is towards the north, and that of Eudoxia is further to the east, all of porphry, that is Roman (stone).” In the northern stoa, “towards the north, is a cylindrically shaped sarcophagus, porphyry in color, that is, Roman, in which is laid the wretched and abominable body of Julian the Apostate. another sarcophogus, porphry, that is, Roman, in which is laid the body of Jovian who was emperor after Julian.” Constantine VII is not overly criticizing as he lists the Emperors, but clearly he despised Julian the Apostate.

Mesarites also described the mausolea in his description of the church, which is from the very end of the 12th/very beginning of the 13th century. His description includes a lot more judgmental lines than the description of Constantine VII. First he lists those in the mausoleum of Constantine, giving us a good idea of who was buried in each mausoleum. Mesarites said “This whole church is domical and circular, and because of the rather extensive area of the plan, I suppose, it is divide up on all sides by numerous stoaed angles, for it was built for the reception of his father’s body and of his own and of the bodies of those who should rule after them. To the east, then, and in first place the body of Constantine, who first ruled the Christian Empire, is laid to rest within this purple-hued sarcophagus as though on some purple-blooming royal couch–he who was, after the twelve disciples, the thirteenth herald of the orthodox faith, and likewise the founder of this imperial city. The sarcophagus has a four-sided shape, somewhat oblong but not with equal sides. The tradition is that Helen, his mother and his fellow-worker for the orthodox faith, is buried with her son. The tomb toward the south is that of the famous Constantius, the founder of the Church. This too is of porphyry color but not in all respects similar to the tomb of his father, just as he who lies within it was not in all ways similar to his father, but was inferior to his father, and followed behind him, in piety and in mental endowment. The tomb toward the north and opposite this, and similar to those which have been mentioned, holds the body of Theodosius the Great like an inexhaustible treasure of noble deeds. The one toward the east, closest to this one, is that of Pulcheria. She is the honored and celebrated founder of the monastery of the Hodegon; see how she, a virgin herself, holds in her hands the likeness of the all-holy Virgin. This tomb holds the dust of him who was an emperor among wise men and a wise man among emperor (Leo the Wise). This is the tomb of the Empress Theophano, the worthy and venerable, whose memory is everlasting, whose husband was the Wise Emperor, the truly wise Empress, who lived a praiseworthy life; ‘for the first wisdom is a praiseworthy life,’ as the holy writings say. This is the tomb of Constantine (Porphyrogennitos), the first emperor born in the purple, and her son whose name is great in righteous judgment. This is the tomb of Zeno, the Arianizing emperor, who for this was cast out of the kingdom of heaven. This is the tomb of Anastasius Dikoros, concerning whom the story is that fire was sent from heaven and consumed the emperor, who had previously been threatened with this punishment because he attached himself to those who attribute to Christ one volitional activity and one will. He built a house which had its whole fabric made of baked brick and mortar, a kind of second Noah’s ark, so that he might escape, as he thought, the disaster which threatened him; he was a fool, who hoped to escape the threat which the voice of God uttered against him. This is the tomb of Basil the Macedonian, who by most divine providence was raised from a lowly walk of life to the eminence of the imperial position-he who, they say, removed a quantity of the decoration from the church of the heralds of God and transferred it to the sacred house which he himself built in the name of the chief marshal of the powers on high, the church whose title is the Nea. This is the tomb of Nikephoros Phokas, a most brave and warlike and prudent man, who lost his life by treachery. The tomb in the inner part of the Church contains Constantine (the last burial in the Holy Apostles), born to the purple, the brother of the great emperor who is known as Bulgaroktonos (Basil II).”

But Mesarites did not stop there, he also walks us through the mausoleum of Justinian and list the tombs there as well. Continuing his tour he wrote “Let us go on a little, if it seems good to you, O spectator, to another building, which is called a heroon, and is named by some a place of mourning because there are buried in it the emperors, who are, one might say, heroes. You see another building with five stoas like that pool at the Sheep Gate of Solomon; for here too there lies a great multitude of those who have lost their vigor because of the weakness to which every man is subject through sin. But these men too will spring up at the coming of the angel, when he sounds the trumpet to all the world at the second coming of the Lord, and they will stand before the impartial judge of all, the Savior Christ. This tomb at the east is that of Justinian, whose name is great and celebrated for just judgment and observance of the law, who is the founder of the great shrine of the Wisdom of the Logos of God (Hagia Sophia). His name will be celebrated from generation to generation as the doer of the most mighty deeds, as the supreme ruler, who cast down great princes who had subjected the whole world to the power of their might. The tomb close to this and toward the north is that of Justinus, the grandson of Justinian, a man celebrated for his justice and greatly renowned for his piety, who also built what was lacking in the great shrine of the Wisdom of the Logos of God, and completed it and resettled the dome, which had fallen, and skillfully raised it. The tomb toward the south is that of his consort Sophia, a devout and seemly woman, really wise and truly fearing the Lord; for the beginning and end of wisdom is the fear of the Lord, as the holy writing says. This is the tomb of Heraclius, whose fame is wide and resounding in Persia and the lands about it. He performed many labors, surpassing, as one might say, those labors of Herakles; and before performing these he put off his imperial robe and as he set out on his campaign, put on blackhued boots, and then returned when he had turned them red, dyeing them in the blood of the barbarians. This green sarcophagus is that of Theophilos, who belched forth the venom of impiety against the holy images and poured it over those who venerated them. Whether, indeed, as the story is, he was saved by the remarkable assistance and zeal of the orthodox Theodora, his wife, through the restoration and veneration once more, at her behest, of the holy and divine images, I myself cannot say certainly; but let him speak who was tattooed by him-and is known to this day as the Graptos-on account of his veneration of the august images, he who is himself inscribed in the Book of Life. This tomb of Sardian stone belongs to Theodora(wife of Justinian),” the prudent empress, whose work this celebrated and admired church of the heralds of God is (she was credited more than Justinian for the construction of the Holy Apostles). And concerning the others, why should we care, since their memories are buried with them in their tomb?” Clearly Mesarites feels the others buried were not worthy of mention, clearly a deliberate snub.

The mausoleums were so important that Emperors who could not receive burial here had to emulate to the best of their capabilities. As the centuries wore on, there was less space, and some were excluded from burial in the Holy Apostles. The mausoleum of Constantine eventually had twenty sarcophagi, and the heroon of Justinian held twenty-three. New spaces had to be found as it got more crowded and eventually completely full. Romanos Lekapenos built for himself the Myrelaion, with had both a palace and a church which he and his family were buried in. Romanos Argyros built the Peribleptos monastery for his tomb. Nikephoros Botaneiates was also buried there after restoring it. Constantine Monomachos built the Mangana church, where he and his mistress Maria were buried. Alexios Komnenos was built at the Christ Philanthropos Church when he died.

After the death of Alexios Komnenos his son and the next Emperor, John Komnenos, truly showed the influence of the Holy Apostles. He and his wife Irene of Hungary founded the Pantokrator monastery. This was to be the dynastic mausoleum of the Komnenos dynasty. It was a magnificent construction in the context of its own time, and still stands today as Zeyrek mosque. In the sources the burial area was described as “heroon of the exterior,” which was the revival of “an ancient term meaning monument for heroes that had previously been used for the Mausoleum of Constantine at the Holy Apostles.” On the west wall was a place for John’s deceased son Alexios who suddenly died in 1142, and John joined him when he died the next year. Manuel Komnenos, the son and successor of John, buried his wife Bertha when she died in 1160 in Pantokrator. Manuel himself was buried there, and had the Empire not been shattered in 1204 Pantokrator would have been far more developed as a mausoleum.

The porphry sarcophagi of the Byzantine Emperors are of particular fascination to me. There were many sarcophagi and only the early ones were made from porphry, but only a handful exist still. It is amazing that for nearly a thousand years from the time of Constantine’s death to 1204, you could walk into the Imperial Mausoleums at the Holy Apostles and see a true museum of Emperors. You could find Constantine, Theodosius, Justinian, Nikephoros Phokas, and most others who had ruled until the early 11th century when the mausoleums became full. Imagine seeing such history, sadly those who had the best view were the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade, whom in their lust for gold lifted the stone lids and robbed the sacred graves of their treasures. Basil II could have been the last Emperor buried there, but he chose a church outside the walls where soldiers frequented. After the liberation of the capital in 1261 the tombs were put back in order but without their treasures.

In the early centuries there is literary evidence of a palace complex associated with it. In the 5th century, the area around the Holy Apostles was thriving and the the Emperor Marcian built his forum in this region of the city. The first wife of Theodosios the Great built a palace nearby, the palace of Flaccilla. It was important enough that even in 532 during the Nika riots the opponents of Justinian took an imperial insignia from the palace to crown Hypatios as a rival Emperor. The fact it held an imperial insignia suggests that there was a palace complex nearby, if not directly associated with, the Holy Apostles.

Basil I removed mosaic and marble decoration from the Holy Apostles for use in the church called the Nea. Mesarites criticized that, but did not include the fact that Basil I also restored the Holy Apostles.

FOURTH CRUSADE:

I am sure that like any other source of wealth that the church itself was looted by crusaders as it surely held many treasures. However, the desecration of the imperial mausoleums is what gets the most attention in the sources. Although the mausoleums were not where the Crusaders initially looked for wealth during the sacking of Constantinople, the Latins left in charge of Constantinople ruling the “Latin Empire” found themselves in need of cash.

Choniates records the looting of the mausoleums with disgust: “Exhibiting from the very outset, as they say, their innate love of gold, the plunderers of the queen city conceived a novel way to enrich themselves while escaping everyone’s notice. They broke open the sepulchers of the emperors which were located within the Heroon erected next to the great temple of the Disciples of Christ and plundered them all in the night, taking with utter lawlessness whatever gold ornament, or round pearls, or radiant, precious, and incorruptible gems that were still preserved within. Finding that the corpse of Emperor Justinian had not decomposed through the long centuries, they looked upon the spectacle as a miracle, but this in no way prevented them from keeping their hands off the tomb’s valuables: In other words, the Western nations spared neither the living nor the dead, but beginning with God and his servants, they displayed complete indifference and irreverence to all.”

It is sad to picture what happened, I wonder if they even spared the body of Constantine the Great from looting and desecration. However, I do not believe Choniates would have mentioned Justinian, and not Constantine, if both tombs had been ravaged. Robert de Clari does note the presence of Constantine, saying “that Constantine the emperor lay there and Helena [Constantine’s mother], and many other Emperors” were buried there…so perhaps the Crusaders held it in some reverence.

THE HOLY APOSTLES DURING THE PALAIOLOGAN PERIOD (1261-1453):

In later Byzantine history it was still important as a monument of the city. The body of Constantine was always venerated, as well as several other saints and Emperors. It was so symbolic and important that even when the city was lost to the Romans after the Fourth Crusade, the Emperor John Doukas-Vatatzes paid for the Holy Apostles to be restored by the Latin occupiers who had desecrated it in the first place. There had been an earthquake, but the Emperor of Nicaea put up a large quantity of money, which likely saved the church from falling into complete ruins at that time.

When Emperor Michael VIII Palailogos entered the city after the eviction of the crusaders in 1261, he still found that the Holy Apostles needed work. Both he and his son and successor Andronikos II undertook repairs for the building. Michael VIII even added a small triumphal column, reviving an ancient tradition as he rebuilt the city as best he could after it’s liberation from the Latins. On top of the column was a kneeling bronze statue of the Emperor Michael holding a model of Constantinople offering it to a standing Archangel Michael. This shows that even during the period of imperial absence from Constantinople, the symbolism of the Holy Apostles endured and Michael restored and built on that. There is also evidence that two significant synod meetings were held at the church of the Holy Apostles in the 15th century in 1416 and 1440. This shows that despite what some say, the church was not just in total ruins in 1453 as it was being used in meaningful ways not long before the fall of the city.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE HOLY APOSTLES:

In a chapter from The Holy Apostles: A Lost Monument, a Forgotten Project, and the Presentness of the Past, scholar Julian Raby explains some of the symbolism in the transformation of Constantinople which took place after the Ottoman conquest of the city. He wrote that “Mehmed’s victory realized a dream that the Dar al-Islam had harbored for eight hundred years—the capture of Constantinople. But Mehmed’s vision of a triumphant city could barely begin to be realized until a decade later, when he embarked on his major architectural campaign. In 1453, the preservation of Hagia Sophia was testament to continuity, and ceding the Holy Apostles to the Patriarch was a symbol of accommodation. In 1462/3, on the other hand, the Holy Apostles was erased to make way for Fatih Camii.” Essentially, the conversion but with a high degree of preservation for Hagia Sophia promoted the continuity of the fabric of the city but a new Islamic way. The destruction of the Holy Apostles symbolized the destruction of the Roman imperial past and the creation of the new Ottoman imperial future.

Though the Church was still intact in 1453, and it almost seemed destined to survive into the Ottoman period, there was a abrupt change. There was no Patriarch of Constantinople in 1453, and Mehmed appointed Gennadios Scholarios in January of 1454 to the top position and initially allowed him to use the Holy Apostles. There is some academic debate over when Gennadios was moved from Holy Apostles to Pammakaristos however. The church was demolished in the early 1460’s, so certainly by then.

We have some writings from Gennadios after 1453 which shed some light on the situation in Constantinople at the time. Turkish historian Nevra Necipoglu of Boğaziçi University, analyzing these works, dates the transfer of the Patriarch from the Holy Apostles to Pammakaristos to 1454, earlier than some others have historically placed it. She supports with the writings of Gennadios. Firstly, there is a letter titled the “Pastoral Letter on the Fall of Constantinople,” which explicitly states was written at the Pammakaristos church. Necipoglu acknowledges there is no date on that letter, but makes valuable insights to help situate it. She contextualizes it because Gennadios refers to the letter in “a subsequent pastoral letter, which is datable on the basis of evidence to October 1454, we can almost be sure that the patriarchate had moved from the Holy Apostles to the Pammakaristos shortly before October 1454, hence in the late summer or early fall of 1454.”

Julian Raby posed the question: “What a difference a decade made, from the magnanimous grant of the church to its demolition. What prompted such a reversal in the church of the Holy Apostles’ fortune?” It is actually rather surprising, as Raby noted, that Mehmed would ever allow the Patriarch to be in a church with such powerful significance. The legacy of the Roman imperial past was in this church, the body of Constantine itself, and the tombs of countless others. It symbolized the eternal nature that had so recently embodied imperial rule.

Raby tries to answer his question and explains that Mehmed had reasons to be pragmatic, especially while he consolidated his power. He had to guard against any internal strife, and he had an empty capital which he desired to repopulate. “Few Muslim’s wished to abandon their homes for the uncertainties of a pillaged city, under the threat of Latin revanche. When persuasion failed, Mehmed forced settlement, and in order to make the city a magnet for Orthodox Greeks (Romans), selected not a secular leader such as Loukas Notaras but a religious leader,” Gennadios Scholarios. Mehmed started off by gifting the new Patriarch with “a pastoral staff and a newly made silver-gilt cross, as well as a robe of cloth-of-gold. Above all, Gennadios was granted the second church of the city, the Holy Apostles. Reestablishing a patriarchate made perfect political sense; granting him the Holy Apostles was a gesture of reconciliation prompted by the reality of Mehmed’s position in 1454.”

As Necipoglu and Raby agree, “within less than a year, Mehmed regained possession of the Holy Apostles, however, with Gennadios leaving the church.” The next question to answer, and with no straight forward answer, is why did the Sultan take his gift back? The Byzantine writers after Ottoman rule say that Gennadios made a choice himself to leave the Holy Apostles because they were alarmed by the corpse of a Greek who was found dead nearby. In this narrative, the Patriarch felt concerned with the safety of the area, and thus asked Mehmed to move to the Pammakaristos instead. The Holy Apostles was recorded to be in a poor state in 1454. It is possible that the Holy Apostles being so large and in need of repairs on a more monumental scale was too much for a church which was at this time not rich. The churches had all been looted in 1453 by the Ottoman soldiers which captured the city. Most of the priests and clergy were sold into slavery and had to be ransomed back. Gennadios himself was heavily involved in that process of freeing captured Byzantine prisoners. It is genuinely possible that the Patriarch chose to move, and that Mehmed simply used that opportunity to build his own symbolic successor mosque on the city of the ancient church.

However, it is also possible that it was not forced. Steven Runciman argued that the body of the Turk was planted there to intimidate the Greeks into leaving the area. Perhaps as he was planning for the building of the city he came to see that the Holy Apostles was “the symbol of Byzantine imperial longevity,” and replacing it with a mosque would suit his goals and ambitions perfectly. The mosque was associated by Ottoman historians as trumpeting “Mehmed’s conquest of Constantinople, the peerless city no Muslim had succeeded to take before him, and cited a hadith of the “prophet that blessed the leader who captured the city.”

Yet another question which posed by Raby is did Mehmed see “the holy Apostles as nothing more than a site to be cleared, leaving space for him to place hos mosque on the highest hill of the city. Or did the site resonate for Mehmed…the fact he granted it to Gennadios suggests he was mindful of its importance, but critical to any answer is whether Fatih Camii stands exactly on the site of the Holy Apostles or just in its approximate neighborhood. Necipoglu addresses this same subject, saying that perhaps Mehmed initially gave the church away too easily without realizing just how important it was. She wrote: “A crucial matter to consider in this respect is whether the actual request for the patriarch’s removal from the Holy Apostles came from Gennadios himself. Some scholars, elaborating upon the reference to the murdered man n the patriarchal chronicles, have assumed that the corpse was planted by a largely Muslim local population that was hostile to Christians and resented the presence of the Patriarchal institution in the area. Yet the existence of a sizeable Turkish population there in 1454, which is not supported by any other source, cannot be inferred…Therefore, rather than local hostility, what pushed Gennadios and his staff out of the Holy Apostles may well have been a direct interference on the part of Mehmed II, which the 16th century sources, composed in order to praise the sultan’s magnanimity toward the patriarchal institution and to emphasized his good relations with Gennadios, were likely to gloss over.” Thus, even if Mehmed did force Gennadios, the later Patriarchs wanted to highlight the privileges he gave to Gennadios instead because they wanted the Orthodox Church of their time to be respected as an institution.

Thus it is hard to answer the question of why the Patriarch moved. The sources would not want to blame Mehmed in their texts, but that does not mean that the Patriarch was forced out by the the sultan either. Necipoglu adds her thoughts as to why Mehmed may have had a change of heart: “It is not thus inconceivable that the murdered man — if indeed he is real and not a fabrication of later sources — was planed there by the order of the sultan, who must have had second thoughts about his initial grant of the Holy Apostles to the Patriarchate. The reasons for Mehmed’s possible change of mind are not difficult to surmise. Standing prominently on the city’s highest hill, Holy Apostles was the second largest church and second most important religious symbol of the Byzantine Empire after Hagia Sophia. It was also an important political symbol of the city’s imperial heritage, with it’s two mausolea housing the remains of Constantine the Great and Justinian I, its founder and rebuilder, respectively, along with the tombs of most other pre-11th century Emperors. Mehmed II, extremely concerned right after the conquest of Constantinople about attracting former Byzantine inhabitants to the depopulated city, and perhaps not sufficiently aware at that time of the symbolic significance of the Holy Apostles, had ceded the church to Gennadios.” But then, he realized it was too dangerous a symbol, and chose Pammakaristos as a less politically significant structure to move the Patriarchate to. But to be fair, Necipoglu nor any other scholar have definitive answers. She acknowledged that “as reasonable as that speculations (that Mehmed forced the move) seem, we cannot entirely discard the possibility that Gennadios himself may have requested the move…Could it perhaps not have been that that Holy Apostles was too big or too dilapidated, and thus beyond the means of the Patriarchal administration and the Orthodox community to maintain?” It is a mystery which fascinates me personally, but I do not have the answer, no one truly does. So I have tried to be objective and offer both possibilities.

Raby believes Mehmed saw purpose in the site itself, it was not just any empty space. It was perfect for a powerful symbolism. For Mehmed the destruction of the Holy Apostles and the replacement with Fatih Camii (“Conquerors Mosque”) was highly symbolic. It seemed Mehmed wanted some continuity, but harnessed in a new Islamic form. Somewhat like how Constantine used many ancient Roman elements even as he created his new Rome. Julian Raby wrote: “If I am correct in suggesting that Mehmed built directly over the Holy Apostles, then the tomb of the founder of the new (Ottoman) Constantinople lay near the founder of the first Constantinople. If the mihrab of Fatih Camii did indeed stand over the tomb of Constantine, then the mihrab established by the man who conquered Constantinople stood over the tomb of the man who established Christianity as an imperial religion. One marked the future, the other the past.”

Ken Dark and Ferudun Ozgumus try to make sense of it: “What is certain is that there was only a very short interval between the disuse of the Church of the Holy Apostles and the construction of Fatih Camii. After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, the church was briefly employed as the Orthodox Patriarchate under Gennadios II Scholarios, but the Patriarchate was relocated in 1461 to St Mary Pammakaristos (Runciman 1968, 169, 181–4). The Church of the Holy Apostles was then demolished to make way for the construction of the mosque. It is usually assumed that the destruction of the church complex was complete and rapid. Even Pierre Gilles, who visited the site within a century of its disuse, says that nothing remained apart from a cistern and the imperial sarcophagi.” However, it seems that however small they may seem, some pieces of the church exist in subtle ways.

THE REMAINING IMPERIAL SARCOPHAGI:

The most iconic elements of the Holy Apostles which still exist are the rather noble looking porphyry or “Roman” stone sarcophagi. While we can, with academic caution, identify the rounded one as likely to be that of Julian, the others are not so straight forward. First, let me start with this little fragment pictured below. I have seen this labelled as possibly being the sarcophagus of Constantine the Great. While that is theoretically plausible, there is not really any specific evidence to support it. In fact, there is zero evidence that this was part of a sarcophagus of any kind. Mango puts it well “considering its small size, it would indeed be rash to argue that it formed part of a sarcophagus and not some other sculpture.” The point is, who knows what this is? It does look like early Byzantine/late Roman period, but what it was part of is unidentifiable. Although the Istanbul Archaeological Museum takes that leap of faith, I cannot. There is just not enough evidence for that conclusion.

Setting that fragment aside, we can move to the other remaining tombs of pieces of tombs that still exist today. A 19th/early 20th century historian by the name of Richard Delbreck believed the sarcophagus at the Hagia Eirene was Constantine the Great’s. But, to be fair, that really cannot be much more than hunch. There is nothing specific to identify that sarcophagus with Constantine in any strong way. Anyway, Mango accounts for eight of the 10 known sarcophagi. Below is a screenshot of his accounting of the porphyry sarcophagi.

In 1750, three sarcophagi which had likely been brought to Topkapi by Mehmed, were found on the grounds of the Ottoman palace. Cyril Mango explains how most of the sarcophagi we have from the Holy Apostles were found in the Seraglio (a name for Topkapi palace). The three sarcophagi in front of the Istanbul archaeological museum came from the second court of Topkapi. The three sarcophagi, known from the drawings above and the accompanying descriptions, are rather intriguing. The first two are harder to identify than the third one, because they are gone. But they do not appear to be any of the ones we have in the present.

The most fascinating one to me, is actually not from the Holy Apostles. And although that is the case, I will still discuss it here as Pantokrator was a successor mausoleum inspired by the Holy Apostles. Mango wrote: “Sarcophogus no. 3, of which only the lid was found, was of a most unusual, if not unique, shape. It reproduce the form of a church crowned with seven domes. The exact arrangement of the dome is not clear owing to the faulty perspective of Flachat’s drawing, but it appears that two were disposed alone each of the long sides of the sarcophagus, one in the middle of each of the short sides, and one– the tallest–in the center…this is almost certainly the tomb of Manuel I Comnenus.” Copying the translated description of Choniates, Mango noted that “we know that Manuel was laid to rest in the monastery of Pantocrator, under a stone which was parted into seven pinnacles.” The Pantokrator was one of the earliest structures to be converted into a mosque, and Mehmed seems to have saved this unique lid. What has happened to it since, who knows, clearly it was destroyed or it is buried somewhere else waiting to be discovered. I wish it was in the museum, what an exhibit that could make.

REMNANTS OF THE CHURCH TODAY?:

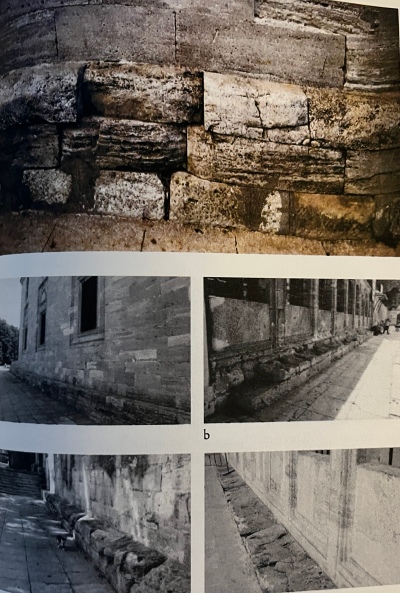

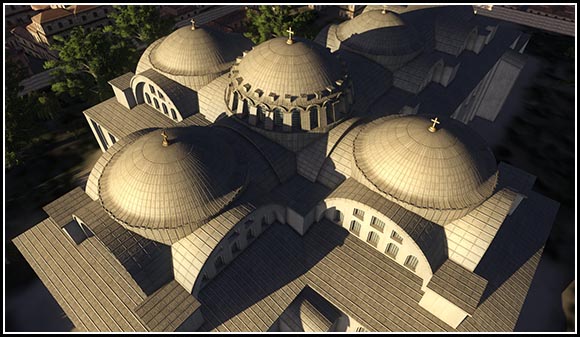

Ken Dark and Ferudun Ozgumus published an articled entitled New Evidence For The Byzantine Church of The Holy Apostles From Fatih Camii, Istanbul in 2002. In it some tantalizing possibilities were discussed. The summary of the publication: “The Church of the Holy Apostles was one of the most important buildings in Byzantine Constantinople. The mausolea of Constantine the Great (the main imperial burial place until the eleventh century) and of Justinian I were in the complex surrounding this vast cruciform church. Nothing of this complex appeared to have survived its demolition to clear the site of the Ottoman mosque complex of Fatih Camii after 1461. Fieldwork in 2001 recorded walls pre-dating the fifteenth-century phase of the mosque complex, still standing above ground level and apparently including a large rectilinear structure. This is identified as the Church of the Holy Apostles and an adjacent enclosure may be that containing the mausoleum of Constantine the Great. The reconstructed church plan resembles those of St John of Ephesus and St Mark’s (San Marco), Venice – churches known to have been modelled on the Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople.”

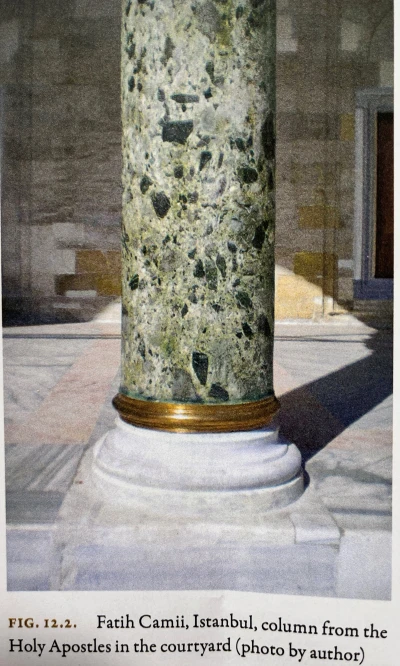

This highlights the possibility that there are remnants of the Holy Apostles today in the mosque which Mehmet built over it after it was demolished. Surely, as was common in the early period of Ottoman Constantinople, elements of the Church were reused in new constructions. The Holy Apostles would have had many fine marble revetments and columns fitting for a new building. The courtyard of Fatih Camii has Byzantine columns in it which likely came from the Holy Apostles.

There are parts of Fatih Camii which still exist that seem to be part of the Holy Apostles which Raby details: “The most notable of these features are three courses of very large and heavily eroded ashlar that form the visible base of the south wall of the courtyard of the mosque. The three courses protrude from the line of the upper Mehmed period ashlar, and the stones differ in type, size condition, finish, and mortar from the Mehmed ashlar. The top course has holes that suggest they were intended to take ties to connect to a now missing course above, and in at least one case there is an iron cramp still in one of these holes. This wall aligns with a run of similar masonry east of the steps, and this continues in uninterrupted fashion along the south side of the cemetery courtyard.” This and other elements are “difficult to explain if it did not belong to a structure that preceded Mehmed’s.” The preceding structure would have be the Holy Apostles as there was no intermediate structure.

Ironically, despite their ancestors having been the ones who despoiled the Holy Apostles during the Fourth Crusade, Western sources lamented the destruction of the grand church. In A History Built On Ruins: Venice and the Destruction of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople by Janna Israel, a Venetian reaction is recorded. She described a unnamed Venetian source which said “A great church, the great cry, The Apostles. With a high voice, it says, O Empress Theodora, Come and See your sacred edifice. I do not believe I have ever thought it would come to this.”

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE BODIES FROM THE IMPERIAL MAUSOLEUMS?

Although it is difficult to infer exactly what happened during the Fourth Crusade, it does not seem that the mausoleums lost all of their resting inhabitants. Constantine himself seems to have been spared, as there is truly no way Choniates would not have reacted in horror to his desecration. The tomb of Constantine is specifically mentioned by Russian pilgrims visiting the city, such as Ignatius of Smolensk, who visited at some point between 1389 and 1405.

When the Holy Apostles was ceded to Mehmed and no longer part of the Orthodox world, the tombs became the property of the sultan. There is no record of what was done with the bodies, unfortunately. However, as the sultan possessed them, it would have been the choice of the reigning Ottoman leader to decide. Raby says “Mehmed gathered in the Topkapi Palace items from these imperial tombs of the Holy Apostles and from the church’s Christian relics. The Topkapi Palace became the resting place for an impressive array of monumental stone items taken from four principal sites: the mausolea of the Holy Apostles, the monastery of the Pantokrator, the Augustaion next to the Hagia Sophia, and the Hippodrome.” He added that the “sarcophagi from the Holy Apostles were not removed as building material, as some have suggested: of the ten porphyry sarcophagi known to have been in the imperial necropolis of the Holy Apostles, eight are still extant, and the remaining two can be accounted for. Of these ten, four, if not five, were found within the grounds of Topkapi Palace, and another was for a long time on the site of the former Eski Saray, the first palace that Mehmed built, in the center of the city. That this was a deliberate collection of imperial sarcophagi is supported by the fact that another find in the grounds of the Topkapi Palace, the seven-domed tomb cover of Manuel I Komnenos, was taken from the Pantokrator, part of which had become the mausoleum of the Komnenian and Palaiologan dynasties, effectively the successor to the Holy Apostles.”

My opinion, and this is an opinion, is that Mehmed gathered all the sarcophagi and perhaps a later more Islamic fundamentalist Sultan disposed of the bodies and they were carelessly left outside. Clearly, at some point, the body of Constantine was “thrown away,” in some form another. It is not known when exactly this occurred, but, at some point they disappear without record. It is something I wonder about, it is unfortunate that the body of Constantine cannot be found in the Patriarchal Church today.

THE HOLY APOSTLES IN CEREMONY:

Constantine Porphyrogennitos tells us some useful information in his Book of Ceremonies about the Church. In Book 1, Constantine described the procedure for Easter Monday at the Holy Apostles and said that the Emperor would arrive in a procession, then sit in a narthex and wait for the Patriarch. When the Patriarch came, the Emperor and Patriarch would enter through some royal doors together. The Patriarch would go into the sanctuary first and the Emperor would leave a gift on the altar. Then they would enter the mausoleum of Constantine, the older of the two mausoleums, and ritually light candles. First on the tomb of John Chrysostom, and then Gregory the Theologian, and then the tomb of Constantine the Great. Then they would light candles on the tombs of the two patriarchs Nikephoros and Methodios, and then the Emperor would enter the mausoleum of Justinian alone, and pay his respects there while the Patriarch would begin the liturgy. He would then exist the mausoleum of Justinian, go up a spiral staircase into the katechoumenia gallery and sit through the liturgy until taking communion from the Patriarch.

Constantine Porphyrogennitos, in another passage, described the Feast of Constantine and Helen, which occurred annually on May 21. He wrote as a heading for the passage “All that must be observed in keeping with the current celebration of the annual commemoration of the holy and great Constantine and the consecration of the holy crosses set up in the New Palace of Bonus.” He said the the Emperors would take residence in the Palace of Bonus at least one full day before the Feast, then they would set off to the Holy Apostles from there. The Emperor would arrive at the Holy Apostles, and change into ceremonial vestments, before going through the Church to the mausoleum of Saint-Emperor Constantine the Great. The Patriarch would meet the Emperor there, and (keep in mind, Constantine Porphyrogennitos wrote this as his family’s procedure) they would then venerate the tombs of Leo VI, then his wife Theophano, and then Basil I, and finally Constantine the Great. They would bless the apses of Constantine and Helen, and also the Cross of Constantine. This would be followed by a meal in the Palace of Bonus which only the Emperor, Patriarch, and chosen court officials and Bishops would attend.

Paul Magdalino seems to think that the first ceremony was probably more traditional and older, and that the second was clearly designed to use more recent buildings during the time of Constantine Porphyrogennitos, and to venerate the Macedonian dynasty that he hailed from. But, it still carried traditional elements and did venerate the founder of the city, Constantine.

SOURCES:

Nikolaos Mesarites: Description of the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople Transactions of the American Philosophical SocietyVol. 47, No. 6 (1957), pp. 855-924 (70 pages)

Margaret Mullett and Robert G. Ousterhout. The Holy Apostles: A Lost Momument, a Forgotten Project, and the Presentness of the Past (2020)

The Conquest of Constantinople by Robert De Clari (primary source) –

Niketas Choniates – O City of Byzantium, Annals of Niketas Choniates. Translated by Harry Magoulias. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984.

A Homily With A Description of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople by Liz James and Iuliana Gavril

The Cambridge Companion to Constantinople, Edited by Sarah Bassett

Nikolaos Mesarites: Description of the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople. Edited by Glanville Downey

New Evidence For The Byzantine Church Of The Holy Apostles From Fatih Camii, Istanbul by Ken Dark and Ferudun Ozgumus.

The Tombs of the Byzantine Emperors At the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople by Glanville Downey(1959)

The Book of Ceremonies written by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennitos

A History Built On Ruins: Venice and the Destruction of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople by Janna Israel

Studies on Constantinople by Cyril Mango (1993)