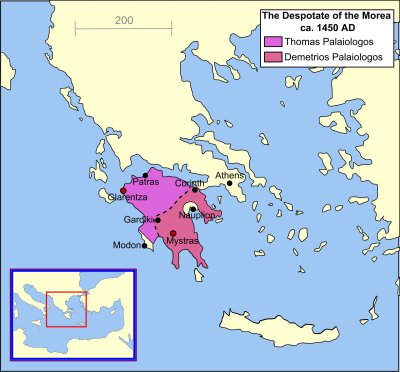

The Peloponnese was essentially the only area where the fortunes of the Romans improved in the empire’s final era. The Despotate of the Morea was eventually able to push out the Principality of Achaea, a Crusader state founded after the Fourth Crusade. It has an interesting story that runs somewhat counter to the rest of the empire.

THE FOUNDING OF THE DESPOTATE:

The Peloponnese had been part of the Roman Empire for over a millenium. However, after the Fourth Crusade, it was conquered by the Crusaders and Venetians. This led to the founding of the Principality of Achaea, which controlled nearly all of the Peloponnese.

However, Michael VIII had sent Roman forces to liberate Greece which won a huge victory at the Battle of Pelagonia in 1262. This was shortly after Constantinople itself had been liberated from the terror of Crusader rule. The treaty which followed gave the Romans a foothold in the southern Peloponnese. The actual Despotate later was founded by John VI Kantakouzenos a semi-independent province, reminiscent of the earlier Exarchates like that of Ravenna and Africa. He sent his son Manuel Kantakouzenos to govern it in 1349. It was still part of the empire under the rule of the Emperor in Constantinople, but its rulers were empowered to manage it. This was how the Despotate of the Morea was born! Manuel Kantakouzenos ruled it for 31 years, allowing it a time of stable leadership which surely helped the Despotate forge strong foundations in a land still contested by the Latins.

THE PALAIOLOGAN RENAISSANCE:

After Manuel died in 1380, the Emperor was John V Palaiologos, and he sent his own son Theodoros Palaiologos to be the Despot of the Morea. From this point on it was a Palaiologan land. Unlike the overall empire, which declined, the Palaiologan family brought success to the Morea. By 1429, they had liberated nearly the entire peninsula from Crusader rule! The Principality of Achaea was eliminated.

After this point there were highs and lows, as the Despotate was protected and prosperous, yet had no external focus for its energies. This led to a lot of local feuding. The Emperor Manuel II even visited and discovered this himself!

THE LAST HOPE:

The Pelopponnese “should have been the springboard of a Byzantine restoration” in Greece – but though it had something of a local renaissance, its political character held it back. In 1415 Emperor Manuel Palaiologos visited and described the nature of the people below:

“It seems to me that it is the fate of the Pelopponnesians to prefer civil war to peace. Even when there appears to be no pretext for such war they will invent one of their own volition; for they are all in love with weapons. If only they would use them when they are needed, how much better off they would be. In the midst of it all I spent most of my time trying to reconcile them with each other.” [The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261-1453 by Donald M. Nicol]

You can get a real sense of grief from Manuel II. It seems like he sees a greater potential in the land and people, if they could harness this militaristic character towards external foes the empire could have been stronger. Constantine XI tried to launch an offensive from the area and had some initial successes, but by the 1440’s there was no real way to make any lasting gains against the Ottomans. Constantine’s brothers constantly fought, apparently they became like the other Pelopponesians.

According to Donald M. Nicol, the people of the Despotate of the Morea “had lost the habit of living under a centralized administration.” The rulers sent from Constantinople seemed like an imposition to the locals, at least initially. The geography of the area, “with its natural divisions of mountains and valleys, promoted separatism and, as in ancient times, feuds between rival clans.” [The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261-1453 by Donald M. Nicol]

CONSTANTINE XI AND THE ATTEMPT TO EXPAND:

The Morea was the only area where things went well. Thessaloniki fell in 1430, leaving it as the only viable province left. Constantine XI attempted to expand the Despotate north when he was in charge, before he was an emperor. He boldly went to war against the Duchy of Athens, a Crusader state vassal of the Ottomans centered on medieval Athens. His goal was to take advantage of the Ottoman distraction with the Crusade of Varna, and to position the Romans to take over Greece if it was successful. Constantine was successful, liberating Athens from the Latins, and even pushed on into Thessaly, but his bold decision to declare war on the Ottomans backfired. I wrote an article on this if you want more info on the Last Offensive of the Roman Empire.

THE EPILOGUE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE:

After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Despotate of the Morea kind of awkwardly lingered on as a rump state, and in submission the Ottoman Empire. It’s rulers were the brothers of the fallen hero Constantine XI Palaiologos, but they were nothing like him. They were squabbling men without his dignity, ambition, or wisdom. This is why Constantine XI had been chosen to be emperor, and not them.

The Despotate still existed, but neither brother dared to claim the imperial title for themselves and try to claim that the Despotate was the continuation of the Roman Empire. That would be an invitation for Mehmed II and his army to visit them. In addition, the Empire of Trebizond still existed, another Roman state but not the Roman state. I say it was not the true Roman Empire because it was a separatist state formed shortly before the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople. However, in the 1450’s Mehmed was just patiently waiting to eliminate both of them. Trebizond would fall in 1461, but and the Despotate fell in 1460. But as the story below will show, they kind of invited their own destruction and likely sped it up.

THE FALL OF THE DESPOTATE OF THE MOREA:

There was immediately trouble in 1453 for the Despots Demetrios and Thomas. Unlike their heroic brother Constantine XI, they were not noble men cut from his cloth, but instead infighting and irresponsible rulers. They now found themselves as subjugated vassals of the Ottomans. And the Sultan would soon realize they were troublemakers.

They had to deal with a large Albanian community, though it was not a majority like some people like to claim today, in particular Albanian nationalists. The Albanians rose in revolt against the Demetrios and Thomas, and things got out of control. In humiliating fashion the Despots had to send word to Mehmed and beg him to help. Mehmed was ready to intervene, technically they were vassals of the Sultan. He must have been amused, but not in a good way. Why keep a vassal around who cannot even keep order?

The Ottomans surely did not want this to get out of control. They were facing stubborn Albanian resistance under Skanderbeg, and surely Mehmed was not looking to see any Albanians controlling the Peloponnese. The Ottomans ended the revolt by the summer of 1454. Demetrios and Thomas were restored, but ordered to start tributary payments to Mehmed.

However, the Despots fell behind on the payments. By 1458 they were 3 years behind on their tribute. The Sultan Mehmed was not happy with the situation. The brothers themselves were infighting as usual and did not agree on what exactly the best future was. Should they embrace the Turks or look West as their fallen brother Constantine had? Neither had much courage anyway.

Thomas was a fan of seeking western aid, and Demetrios believed a more thorough submission to the Ottomans was for the best. Mehmed did not like that Thomas was courting westerners, which he surely saw as more of a threat than the meagre Despotate itself.

In 1458 the Sultan personally led an army to the Peloponnese in order to pay the brothers a visit. Mehmed did not end the Despotate quite yet but demanded a harsher tribute, weakened their power further, took some land concessions, and took many thousands of captives. The Despotate was slowly being drained, insuring there would never be a final battle for it.

Mehmed II was putting a lot of energy and resources into growing Constantinople back into a large city, and settling Roman captives was a tactic. The same thing would happen to the people of Trebizond in 1461. A Turkish governor also controlled the city of Corinth now, keeping an eye on the troublemaking brothers.

Mistra had been spared the horrors of war, and Demetrios resided there and tried to obey Mehmed. Thomas still resisted and even received a small contingent of western troops. But he ended up using them to invade his own brothers half of the Despotate, to the surprise of Demetrios.

The brotherly infighting this time infuriated Mehmed to a point of no return, and in 1460 he decided he had given one too many chances to them. It is almost like they begged him to conquer it with their persistent and incompetent squabbling. By May 1460 he had arrived in Corinth with a large army, and he summoned Demetrios to meet him. Demetrios was afraid to go, fearing for his life.

He refused, and the Turkish army went straight to Mistra while Demetrios intended to flee to the fortified town of Monemvasia. Mehmed sent a Roman official of his, Thomas Katavolenos, to convince the town to surrender, which he did along with persuading Demetrios not to flee. Demetrios had no choice but to go face to face with Mehmed, totally at his mercy.

Demetrios personally went into Mehmed’s tent and was well-received, sitting next to the Sultan. Mehmet made him an “offer,” though he could not really say no. In exchange for the Despotate being incorporated into the Ottoman Empire – Demetrios would receive wealthy estates.

Most towns in the Despotate surrendered, those that did were treated well, those that didn’t were sacked. Thomas had hid the whole time, neither he nor any Westerners had intervened. He fled to Corfu then took the relics of St. Andrew from Patras to Rome where he died in 1465.

In Mistra the Turks took “over the upper city. The Pasha lived in the old Palace of the Despots. The Palace Church of St. Sophia was transformed into a mosque. In the castle on the summit of the hill there was now a large Turkish garrison…In the lower city the Greeks lived on.”

SOURCES:

The Lost Capital of Byzantium: The History of Mistra and the Peloponnese by Steven Runciman

The Last Centuries of Byzantium 1261-1453 by Donald M. Nicol

The Immortal Emperor: The Life and Legend of Constantine XI Palaiologos, Last Emperor of the Romans by Donald M. Nicol.

The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium