ORIGINS:

In the year 860AD the Rus Vikings launched an attack on Constantinople, going for the ultimate prize, but they could not take the city. Despite this hostile start, eventually Viking warriors would serve the Emperors of the Romans. The Varangians originated as simply ordinary mercenaries working for the Romans, just one group among many. They became far more than that, and are probably the most famous Byzantine military unit. They were ferocious warriors known for their bravery and their loyalty to the Emperor they served. They served as shock troops, elite troops sent to join field armies, and as defenders of the capital.

In 874 Constantinople and Kievan Rus reached a peace agreement which lasted until 907, when the Rus attacked the city again. In the reign of Michael III the Rus began serving as mercenaries in the imperial forces. In the 10th century, the amount of Norse and Rus Viking warriors in the army steadily increased. They are mentioned during the reign of Constantine Porphyrogennitos as guards at the court.

But it was in the year 988 that the Varangians truly began to form. Basil II was facing the powerful rebel general Bardas Phokas, and asked the Grand Prince of Kiev, Vladimir the Great to send him Rus warriors to help him defend his throne. Vladimir sent 6,000 men whom he wanted to get out of Kiev because they were “furious at the Prince’s (Vladimir) unwillingness or incapiacity to pay them their wages…” and “…demanded that he show them the way to the Greeks (Romans).” Vladimir also converted to Christianity and married the princess Anna. This conversion to Christianity has had significant effect on history, as it helped bring the Russians into the Orthodox and not Catholic world. Basil unleashed his new Varangian army on the rebels at Chrysopolis and they chopped the traitors to pieces in the ferocious and ruthless fashion they would become famous for.

They helped Basil secure his throne and secured themselves a permanent role in the service of the Romans. Other warriors from Russia, Scandinavia, and later northwestern Europe would come to fight for the Romans in exchange for riches. Basil used them as more than just a bodyguard, he used them as a powerful element of the army. They helped him fight in Syria, Armenia, Georgia, and the Balkans. Basil II was famous for his campaigns, and he brought the Varangians with him everywhere he went.

SCANDINAVIAN VARANGIANS:

Vikings would arrive in Constantinople all the way from Scandinavia itself, not just the Rus. These warriors were not on a state backed mission, these were individuals seeking private contracts with the Emperor their own individual gain. But it is important to remember that the Scandinavians were likely never the only group in the guard, even if they were a useful source of recruits. According to Sverrir Jakobsson: “If there ever was a purely Scandinavian “Varangian Guard” in Constantinople it did not last a long time. By the end of the eleventh century, the Scandinavian Varangians had, to a large degree, been supplanted by Anglo-Saxons and several other foreign regiments had joined as well.”

It actually seems the Scandinavians were most prominent in the 12th century. When Basil took over, it seems to have been Rus warriors, albeit with similar fighting styles. The Norse chronicles which reference the service to the Romans as Varangians mostly seem to reference the Komnenian era, and even the Angelos dynasty period.

VARANGIAN LOYALTY:

The Varangians are probably one of the most famously known elements of Byzantium in modern times. They are often portrayed as being nearly perfectly loyal bodyguards for the Emperors. While they were highly loyal overall, this was not always true in every case. As humans they were of course going to act in their own interests and according to their own principles. And let us not forget that gold was their main reason for allegiance.

The Varangians for example were highly involved with the overthrow of Emperor Michael V, whom had banished the Empress Zoe from the palace. Harold Hardrada had fallen out of favor, and was imprisoned for potentially stealing treasure or other offenses which may or may not have occurred. Some Varangians stereotypically stayed loyal, but most sided with Hardrada in supporting the usurpation of Michael V and reinstating the legitimate Macedonian dynasty. Michael V was blinded, some sources saying Harold himself carried that out. They were no Praetorian guard, but of course as people at times had to act in self-interest. Overall still a very loyal group!

IMPERIAL DIRTY-WORK:

The first mention of a Komnenian Emperor goes back to Isaac I Komnenos. The Patriarch Michael Kerularios was giving him trouble. According to Sigfus Blondal “Isaac determined to dispose of his most bothersome vassal, the Patriarch Michael Cerularius, especially as Michael had made it amply clear that he regarded himself as a maker of Emperors at his own will; we have the phrase ‘I have built you, stove, and i can pull you down if I like‘ attributed to him — one that Isaac would clearly have resented. Accordingly he replied by sending a detachment of Varangians to arrest him when he was officiating at an ecclesiastical function outside the City(Constantinople) on the Feast of the Holy Arch Angels, 8 May 1058.

The Varangians dragged him from the Patriarchal throne in the church, set him on an ass(donkey) and brought him thus to Blachernae and finally carried him to the island of Proconessos in the Sea of Marmara, where he died shortly afterwards. There is typical Byzantine political consideration in this arrangement, for it was highly unlikely that any Greek troops could be trusted to carry out an operation that involved the brutal abduction of the chief bishop of the Orthodox Church…but the Emperors had come to know that in the Northern Barbaroi they had a force which could be trusted to bring this off unhesitatingly.”

Blondal’s passage above shows how useful it was to have highly loyal and elite foreign soldiers. They would not get absorbed into sentimentality, the church could not pull at their heart strings or appeal to their faith. They were sent by their generous master, the Emperor, and they were there to do the job.

VARANGIAN PERCEPTIONS:

Constantinople made a huge impression on the Varangians. The name they used for the city, Mikligard means something like “large city.” It was described as “metal-roofed Constantinople” in a poem by Bolverkr, clearly this was a sign of wealth compared to Scandinavian towns.

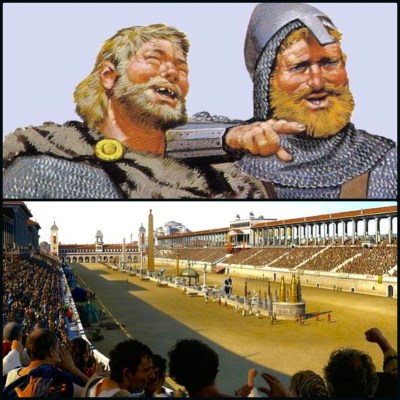

In the Morkinskinna, an Old Norse saga, there is a Varangian description of the Hippodrome. Supposedly an event like this was held to honor King Sigurðr, which had happened over a century before the saga was written:

“Those who have been in Constantinople say that the hippodrome is constructed in such a way that there is a high wall enclosing a field that might be compared with a huge circular farmland. There are tiers along the wall for people to sit on while the games are played on the field. The walls are decorated with all sorts of ancient events. You can find the Æsir, Vọlsungar and Gjúkungar fashioned in copper and iron with such great skill that they seem alive. With this arrangement people have the impression that they are participants in the games. The games are staged with great ingenuity and visual deception so that men look as though they are riding in the air. There are also displays of fireworks, to some extent with magical effects. In addition, there are all sorts of musical instruments, psalteries, organs, harps, violins, and fiddles, and all sorts of stringed instruments.”

It seems this testimony, though not personally experienced by the author, was based on eyewitnesses of the many who had gone to serve in Constantinople and returned. It seems they identified their own mythology in the ancient Greek and Roman statues of the hippodrome. Another description of a the city during the reign of Emperor Alexios Komnenos seems to be recorded as well:

“Emperor Kirjalax [Alexios I] had heard of King Sigurðr and had the gate of Constantinople that is called Gullvarta (the Golden Gate) opened. That is the gate through which the emperor rides when he has been away on campaign for a long time and has won the victory. The emperor had precious fabrics spread on the streets from Gullvarta to Laktjarnir (Blachernai), the emperor’s grandest residence.”

This text shows that the author of the Morkinskinna understood what the Golden Gate was for, that is its use for imperial triumphal processions. Whether or not this King Sigurðr actually was allowed to enter it, the author knew it was a big honor to do so.

THE NORWEGIAN CRUSADE:

Allegedly the 1st king to embark on a crusade was King Sigurd of Norway who led his army by sea all the way to Jerusalem, then Constantinople, & back by land all the way home in a remarkable journey. Many of his men even joined the Varangians! But how much of it is legend?

An Anglo-Norman source known as the Gesta Regime Anglorum is the earliest source, from around 1125: The “king of Norway, in his early years comparable to the bravest heroes, having entered on a voyage to Jerusalem, and asking the king’s permission, wintered in England. After expending vast sums upon the churches, as soon as the western breeze opened the gates of spring to soothe the ocean, he regained his vessels, and proceeding to sea, terrified the Balearic Isles, which are called Majorca and Minorca, by his arms … Arriving at Jerusalem he, for the advancement of the Christian cause, laid siege to, battered, and subdued the maritime cities of Tyre and Sidon. Changing his route, and entering Constantinople, he fixed a ship, beaked with golden dragons, as a trophy, on the church of Sancta Sophia [i.e. Hagia Sophia].” The source also displays some anti-Roman bias, which is not surprising due to Norman-Roman conflict at the time.

But how much truth was there to all that? The problem with this story is that “the earliest Norwegian source of Sigurðr’s travels, Historia de antiquitate regum Norwagiensium, was composed around 1180.” On top of that, it does not have the same version of events. “It mentions Sigurðr’s armed pilgrimage, but nothing is said about a stop in Constantinople or about the king’s relationship with the Roman emperor. Ágrip af Noregskonungasog̨ um, which was composed sometime around 1190, is the earliest reference to a trip made by Sigurðr to Constantinople in a Scandinavian source. There is, however, only a brief mention of his stay there.”

The source recorded that “He went to Mikligarðr and received much honour there from the emperor’s reception and great gifts. He left his ships there as a memorial of his visit. He took off one of his ships several great and costly figure-heads and put them on the church of St. Peter.”

The problem with this source is that it is written later, and the writer is displaying a lack of knowledge by putting the wrong church. Sverrir Jakobson argues that “the most logical reading of the text would suggest that Sigurðr, having journeyed to Palestine with his fleet, only visited Constantinople on his way back from the Holy Land, which fits well with the earlier itinerary provided by William of Malmesbury.”

Jakaobsson added: “Nevertheless, King Sigurðr may have performed some services for the emperor in return for the ‘splendid treasures’ he received in Constantinople. This can be inferred from the fact that he left his ships behind and travelled back to Norway by land, through Hungary, Saxony, and Denmark. The Roman emperor probably had some use for the Norwegian fleet, especially if one assumes that some of Sigurðr’s men also remained behind to man the fleet.”

The 13th century source, the Morkinskinna added even more details regarding “the relation between King Sigurðr and Emperor Alexios” which “is described as very amicable in the Morkinskinna and there is a vivid account of the horseraces that the emperor held in Sigurðr’s honour.” Deciphering fact from fiction seems challenging on this topic! Jakobsson does a good job presenting multiple angles and a view based on the sources.

THE VARANGIAN GUARD AFTER THE FOURTH CRUSADE:

“With the capture of Constantinople by Latin troops in 1204 and the installation of a Latin emperor in Constantinople, the relationship between the Roman Empire and Scandinavia would never again be the same.” -Sverrir Jakobsson

The fate of the Varangian guard after the Fourth Crusade which shattered the Roman world in 1204, is a diminished one. The Varangians were the only ones who fought well on the Byzantine side in 1204, and it seems some went on to serve the Romans afterwards in the splinter states of Nicaea, and possibly Epirus. It’s also possible even the Latin “Emperor” of Constantinople from 1204-1261 had a small retinue of Varangians as well.

The Varangians slowly decline in terms of the quantity of mentions in primary sources after 1261 when Constantinople was freed from Latin rule. According to “The Varangian Guard 988-1453 (Men-at-Arms)” by Raffaele D’Amato, in 1265 “the Bulgarian tsar ambushed a Byzantine army and besieged them in the small town of Ainos; he offered the garrison their lives and allowed them to keep the town in return for releasing the captured former Seljuk Sultan of Rum…the Varangians agreed; when a relief force arrived the next day the furious Emperor Michael VIII had them flogged, dressed in women’s clothing, and led on donkeys around the streets of Constantinople. Nevertheless, until 1272 the emperor employed the Varangians extensively in campaigns to recover territories.”

Sverrir Jakobsson says that “The Varangian Guard survived the capture of Constantinople; there are mentions of Varangians in the service of the Roman Emperor in Nicaea and they were definitely in the service of the Latin Emperor in Constantinople. After the re-conquest of Constantinople in 1261, there are occasional mentions of Varangians up until 1405. In 1329, there were still ‘Varangians with their axes’ guarding the keys to any city in which the Emperor happened to be staying.”

The Roman Empire was increasingly poorer after the reign of Michael VIII Palaiologos and surely that contributed to their downfall. John Kantakouzenos mentions them in his history as still being guards in 1316, 1328, 1330, and 1341. But it seems they were just a smaller retinue of palace guards not a powerful unit of the army as they once had been. Emperor John VII said on a letter to King Henry IV that some English Varangians were active in the defense of Constantinople against the Turks in 1402. They are mentioned in 1404 during Manuel II’s reign as well. But it seems there were no Varangians in 1453 so probably in the early 1400s the Varangians faded away completely as soldiers of the Emperors.

A VARANGIAN LOVE STORY:

There is a very interesting Varangian romance story in Sigus Blondal’s book. The Varangians were famous for their loyalty, but during the reign of Andronikos II a certain guardsmen named Harry (Erris) betrayed the Emperor in order to pursue a love interest! After a conspiracy in Thessaloniki to seize power Michael Angelos Doukas was imprisoned, and guarded by the Varangians. But…“Michael’s sister was also in custody, and it is said that she and Erris fell in love, which her brother discovered, whereupon he determined to use this fact to his own advantage.”

“Finally he promised to marry her to Erris if he could get them out of their imprisonment, which the latter promised to do. Two Varangians were on duty in the prison as guards (the place appears to have been in some extension of the Emperor’s palace), also a young lad who acted as the prisoners’ servant. As he did not trust his guards to join with him in the escape plan, Erris called them in one by one and killed them, but the boy was suffered to live, as they felt that it was cowardly to kill such a young lad, and so he was merely tied up and gagged, and left behind as the three escaped. Since Erris was a high-ranking officer, the guards at the outer gates recognized him and thought that he was moving the prisoners from one place of confine- ment to another, and let them pass without hindrance through the gates. The fugitives reached a ship which Erris had got Michael’s friends and relatives in the City to make ready, and set sail for Euboea, where they hoped to find safety with Michael’s sister, who ruled the district under the protection of the Venetians. Almost as soon as they had weighed anchor, however, a furious storm blew up, and finally they had to seek shelter in the harbour of Rodosto by the Sea of Marmora. Unfortunately for them, there were in the town soldiers who knew of their escape, and the three fugitives were re-arrested and brought back to Constantinople, where Michael was put back in custody. We hear no more of the rogue Erris, but may assume with some certainty that he was executed for treason.”

INTEGRATION:

There is some evidence that a few Varangians integrated into Roman society. “In the late medieval Roman Empire, the name “Varangian” was often affixed to Greek surnames, indicating a person of Scandinavian origin in such names as Βάραγγος, Βαραγγόπουλος, or Βαραγκάτες (Varangos, Varangopoulos, Varangkates). The evidence of such names testify to the integration of the descendants of peoples of English and Nordic origin into Roman society. These “Hellenized” Varangians obtained land and estates both in Constantinople and in northern Greece, on the Aegean Islands, in Asia Minor, and practically all over the empire. The descriptions of Scandinavia and Baltic region in the texts of Palaiologan epoch are also essentially different from that of earlier times and seem to be based on travel accounts. The historian Laonikos Chalkokondyles makes a note of trade contacts between Livonia and Denmark, Germany, Britain, and the “Celts”

VARANGIANS GOING HOME:

What was life like for a Varangian who returned back to his homeland after serving the Emperor in Constantinople? The Varangians earned great honor and riches serving the Romans in Constantinople, however not all Varangians returned home with a happy ending!

Sverrir Jakobsson wrote that: “The dark side of the Varangian experience is also apparent…A Varangian who had returned could prove restless and unable to find a foothold in his home country, and he could also have a target on his back as a high-prized object of vengeance in a feuding society. There were also other ideal types of the Varangians in the saga literature, one of which was service to the Roman Empire as an ultimate life goal” rather than a means to an end.

If they did return to their homeland, they would have to find a way to establish themselves in a rough environment full of war and conflict. For many Varangians, even if they never returned, they lived a life of riches and honor. It’s hard for a Viking warrior to just retire!

SOURCES:

The Varangians of Byzantium by Sigfus Blondal

The Varangian Guard 988-1453 (Men-at-Arms)” by Raffaele D’Amato

https://www.academia.edu/3628861/Varangian_Norse_Influences_Within_the_Elite_Guard_of_Byzantium

English Refugees in the Byzantine Armed Forces: The Varangian Guard and Anglo-Saxon Ethnic Consciousness by Nicholas C.J. Pappas

The Varangians: In God’s Holy Fire by Sverrir Jakobsson