The Answer: Politics! Centuries of Politics…

After 800AD, many in Western Europe called the medieval Romans Greeks for about a millennium. However, the independence of Greece in the 19th century made the Greek label more politically complicated. Yet, still no one wanted to call them Romans, of course. The need for a term a lot of different factions could agree on, but which did not surrender the Western claim on the Roman legacy, was needed.

Many seem to think the term comes from Hieronymus Wolf in the 16th century. But “this origin story is wrong in every significant way.” However his works “did not inaugurate a new paradigm for thinking about the eastern empire.” He simply continued to call them Greeks for the most part, so it was not really a change from standard procedure in academia at that time.

Since around 800AD, with the coronation of the Frankish King Charlemagne as a “Roman” Emperor, western Europeans had switched to referring to it as ‘the empire of the Greeks’ and its subjects ‘the Greeks.’” Before 800, however, they had been widely accepted as Romans in the West. Wolf did not deviate from that paradigm. Calling them Greeks was sufficient for his purposes, and for many other historians. I even see 20th century books using that terminology.

So why did the terms used for referring to the continuation of the Roman Empire in the East, change in Western academia? Why did they switch from calling them Greeks to saying they were Byzantines? Because of “Great Power politics…Specifically, after 1821 there was a Greek state that aspired to expand at the expense of the Ottoman Empire.” This raised a new issue: The Greeks wanted to restore this empire, an idea known as the Megali Idea (the Great Idea). Millions of Greeks still lived in Ottoman lands, and were even the majority in some regions. Essentially, calling it the Greek Empire offended the Ottomans as legitimizing a Greek claim to their lands, especially for Anatolia and Constantinople.

This quote helps understand how the Greeks were thinking: “The Kingdom of Greece is not Greece; it is merely a part: the smallest, poorest part of Greece…Athens is the capital of the Kingdom. Constantinople is the great capital, the dream and hope of all Greeks.” (Ioannis Kolettis, one of the the thinkers behind the Megali Idea. January 1844). While Western Europe was reading works of the Ancient Greeks and trying to help the Hellenes, most Greeks of the time dreamed of Constantinople and retaking what had been the center of their medieval Christian world.

Additionally an Orthodox Christian ethnic group, “Greece was often seen as aligned with Russia, which was almost never the case but it was at one important moment: the Crimean War. Greeks then joined Russia, which was fighting against Britain & France, and Greek fighters & newspapers hyped the slogan ‘Greek empire or death!’”

Western Europe had no desire to further this or any new Greek Empire, which had a negative historical memory to begin with. “Not long afterward, historians writing in the western empires, which opposed this ambition to revive the Greek empire, retired that concept, as it implicitly legitimated Greek imperial irredentism.” Just as in 800 calling them Roman no longer suited them, now neither did Greek!

“They replaced it with that of Byzantium or the Byzantine empire, which was non-committal when it came to the Greek question.” It appeased the Turks, preserved the Roman name for Western Europe, allowed the Greeks to think of the Byzantine Empire as just another name for Greece, and essentially became a neutral term to the contemporary political actors. It was only not neutral to one group: The actual people and their civilization of the past.

From this you can see that throughout history, the name has been changed to suit whatever the political needs of the day are! Not academic needs. It is a cautionary tale, displaying how history is often misused to tell a story for modern purposes, not just an objective truth-seeking exercise.

So what do we do now?

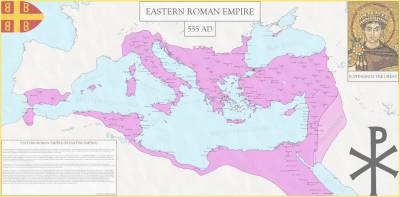

Byzantium as a concept was imposed for the wrong reasons but can be replaced for the right reasons. Anthony Kaldellis proposes calling them “East Romans.” I have been calling them something quite simiar, the Eastern Romans, for a while now. It’s a more clear, accurate, and less disparaging academic label! It has all the positives of Byzantine, with none of the negatives.

A few things to address for those who will raise objections to the term:

- Eastern Romans can be used to indicate is the continuation of the Eastern half of the Roman Empire. It does not have to be a term that means there is also a Western empire. This is an academic label for special purposes, oftentimes just Roman suffices.

This also fits people’s current understanding. We are taught the Western Roman Empire fell in 476, the East continued. The term Eastern Roman is for the Roman story after the 5th century. - Roman has to be in the name for me, Byzantine is useful as a term to distinguish this time period from earlier ones, but it is also problematic in origins and disconnecting them from their heritage and identity.

- Medieval Romans: This does not work as an alternative because this state is not purely medieval, it also includes Late Antiquity. So it is both a medieval and ancient state. While I do use the term medieval Romans, I only use I am referring to the medieval period.

- New Romans: One could use this, as Constantinople was the New Rome. I find this better than Byzantine, but I do not like the idea it was a “new” state, which is also disconnected from their continuity of the Roman state. Constantinople was a New Rome, a new capital, but it was not a “New” Roman Empire.

Source:

The Case for East Roman Studies by Anthony Kaldellis